Where did afterlives fever come from? These reflections suggest a trajectory. Today, amid a lively eruption of usages, afterlife has moved away from longstanding meanings in religious, archaeological, and art studies, as “life after death” or “in an afterlife.” The new fondness for political afterlives has multiplied since the 2000s, when the trauma fashion began to recede. Critical events, catastrophes, empire, and ecological devastation have inspired the turn: that is, to what followed, in lives and forms of living, in performing, publishing, and representing, and in generating an archive of some sort.

Many who putter in afterlives think with the sensory or futures, terms that also saturate – or oversaturate? — the humanities today.

Afterlives is often a heuristic for new experiments with remembrances, visuality, and memory work. Many who putter in afterlives think with the sensory or futures, terms that also saturate — or oversaturate? — the humanities today. Those using afterlives as a framing device often develop a conceit about what followed a disaster or catastrophe. Others are finding afterlives in images, objects, and dreamwork. The evocative term confronts others wherever it goes, like afterwards, aftermath, traces, remains, archive, and curation. What happens to time in such processes?

Ruination as counterpoint

Some afterlives stem from a fresh awareness of grim forms of ruination circulating around and out of empire, the Cold War, and decolonization. Afterlives has never been a strong Ann Stoler word, though she drew important critical attention to ruination as concept and historical process.

Her work has taken scholars beyond trauma and explored enduring effects of catastrophe.

With duress, Stoler steered colonial studies toward often slow, delayed forms of imperial destruction along environmental, material, and political lines into the present, with sensory registers and also dissent. Aiming at what “people are ‘left with’” in the wake of a chemical or ecological disaster, two afters emerge: the “aftershocks of empire” as in corroded landscapes and through the “social afterlife of structures, sensibilities, and things.” Social ruination impairs honor, health, fortune, and futures. In lives touched by toxicities, reappropriations emerge. Those affected may become strategic within politics of the present. Temporalities illuminate injury through duration, endurance, and convolutions of aphasia (Hunt 2019). Stoler’s desolate examples come close to various after- words yet without strong attention to afterlives.

Grappling with history as politics

An important postwar European study marked a new departure in historical writing: Kristin Ross’ May ’68 and Its Afterlives. Ross, in 2002, was already skirting trauma. This rubric of many post-Holocaust histories did not belong everywhere, she claimed, at a time when trauma studies were overwhelmed the humanities.

Ross’s book was the first historical work to place afterlives in its title. She defined afterlives as politics, a kind of grappling with history — with postwar French history. Jettisoning trauma as stultifying, she showed how this 1968 “event” had become saturated by representations ever since. May 1968 had also endured, countered amnesia, and asserted significances in the face of distortions.

Ross confronted social memory and forgetting, ever alert to the ways World War II had fueled a “memory industry” where psychopathological categories tended to occupy the plane of history. Some, notably subjects still seeking futures as collective politics, tended to be bypassed with such castings. Ross rather – already in 2002 – sought an “affective register” for May 1968 and its afterlives, since memory associations suggested not the traumatic but a wide mix of pleasure, excitement, and disappointments.

Plasticity and liveliness

I came to a similar conclusion (though without yet reading Ross) when grappling with a sequel for a Congolese history of stark devastation. How the next generations deal with loss and terrible injuries matters. Yet I sensed that a trauma frame would congeal subjects into overwhelmed victims and survivors, effacing social action and practice.

A Nervous State tackles catastrophe. And afterlives becomes a way to interweave into a history ripe with war, rape, mutilation, and insurgency during King Leopold’s Congo (1885-1908), the festive, rebellious, and dreamlike from this time of atrocity to decolonization, and even beyond. Many afterlives are tender, sensed in ironic perceptions and mutinous unrest. I developed the heuristic through attending to memories, horizons, liveliness, performance, and therapeutic insurgencies. Such motion surged during the Belgian Congo years (1908-60), despite widespread childlessness and sorrow

A theoretical plasticity kept the spectrum wide. Other concepts anchor afterlives, such as verve and agility in this once afflicted rubber region. Georges Canquilhem on latitude — capacities to move and be in motion — enables parsing the buoyant, the advantageous, and the thriving. Gaston Bachelard’s sensory reverie suggests playful daydreaming amid evocative, poetic sounds. Reverie as conceit stirred attending to the grandchildren of those struck by that early colonial time of horrific injury. They moved in diverse colonial presents. Many daydreamed about decolonization. Distractions — fishing, modern dance music, sexual banter, song — generated their energetic afterliving in this late colonial “shrunken milieu.” Dissent, dread, and subterfuge came to the fore amid sensory registers, notably fugitive downtime in refuge spaces near copious fish and riverain sounds.

How the next generations deal with loss and terrible injuries matters.

Rather than portraying Congolese as bereft or forlorn in an aftermath zone, the focus is on accidental encounters and aleatory afterlives, to use that philosophical word that takes history beyond necessity. Althusser called for opening history to uncertainty and the not-yet-imagined. Congolese from this once rapacious region, decades later, knew anger and revenge but were alert to wonder and the unexpected. Their partial autonomy before an ongoing coercive situation came from their skills at secrecy and deception. Dismaying, troubling collective memories remained amix , but bent to the unexpected in and through afterlives.

Aftertime and scientific remains

Wenzel Geissler created a wonderful STS-inspired archaeology of science in postcolonial Africa, Traces of the Future, with Guillaume Lachenal, John Manton, and Noémi Tousignant, gifted all. Aftertime is their word. They stressed “tracing” places and remains from after socialist, Cold War, and developmentalist Africa, times also of “heightened awareness of pastness.”

Journeying in five African countries, they located scientific spaces, medical ruins, past dreams and ways of “being with the past”, encountered but rarely bleak. They focused on intersecting timescales, as if they were contemporary archaeologists. Aftertime speaks to temporalities, past horizons, and material remains. They sought the dreamlike and fictive within scientific sites that once promised development. Their notion of “trace” went with an activity: tracing a density of remains, whether in abandoned grounds or “wastelands.” Scientific remains sometimes generated affective encounters, revealing how Africans looked toward pasts and futures. Afterlives, a word here left implicit, seem to hover within this elastic approach to time and temporalities, caught up with understanding one epoch, Africa’s post-1940, utopian, developmentalist era.

Ruination has little place in this experimental book. One senses a tenacity in moving vocabularies away from consequences and effects to process and method: tracing among material layers. Rejecting the historicist, the project demonstrates ways of gathering memories, archival bits, leftovers, pasts, and futures.

Scientific remains sometimes generated affective encounters, revealing how Africans looked toward pasts and futures.

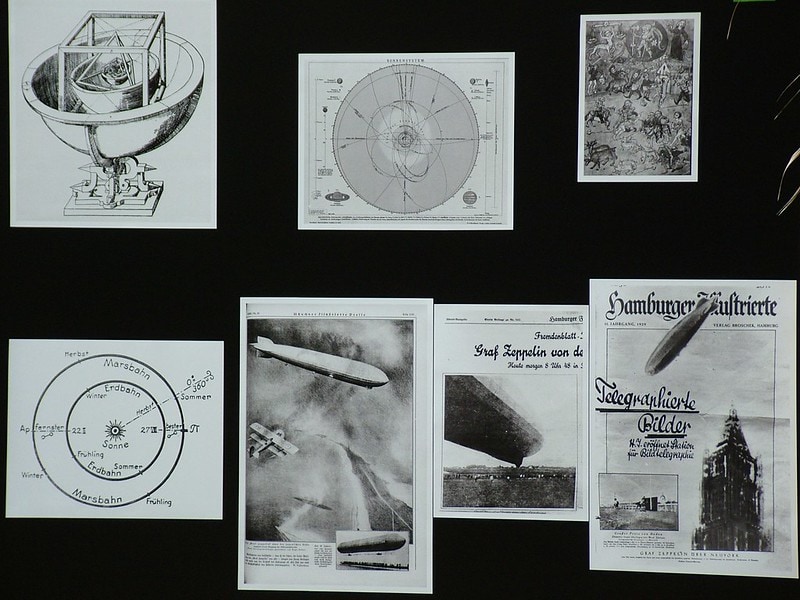

The book’s appearance jars and intrigues. Richly illustrated and curated, at first conveying the feel of a coffee-table book, it has a complex, mixed-hewn layout to its assemblages of texts and images. It is a fine example of an intensely sutured (Hunt 2013) book, one that draws on stunning images by a European artist-photographer, but also everyday archival and visual snapshots, all complicating the sensation of this book-object. If the tome highlights several methodologies, one is the curatorial.

We are all curators now

An intense attention to layout captivates, since it steers readers’ senses toward plasticity in time, place, and remains (Hunt 2018). Such sensibilities suggest the practices of German art historian and cultural theorist Aby M. Warburg (1866–1929) who likely inspired the atlas-like quality of Traces of the Future with its assembly techniques. Warburg created a visual memory atlas in the 1920s, layering images, experiences, and epochs. His methods of ordering images and stirring audiences has become fashionable among historians, artists, and curators. At the core of it all was Warburg’s concept of Nachleben – afterlife, whether as survival or remain.

Warburg’s idea was that meanings emerge within and from the intervals between images, and these come from a mix of times and places. He also conceptualized collective remembering, combining memory with elements from various durations and seeking to move beyond a historicist fixation with turning points in history. Warburg was averse to historicist time and reckonings, adverse to aiming at empiricist anchoring to precise locations and dates.

Tracing an image’s movements detaches it from any sense of a correct milieu, a method Warburg performed for classical images reappearing during the Renaissance. Visual afterlives offer ways of understanding something transhistorical, symbolic, or psychological – or, I would add, something political about history and the present. Warburgian methodology curates unusual layers of text and image – and today many are adding acoustics and sound. Associative thinking and unexpected image sequencing are methods drawing attention to repetitions and patterns and seeking new arrangements. Nachleben also implies a disturbed sequence: to sequence is to unsettle, alluding to possibilities and risks or a stirring of uneasiness.

Whether we are engaging memories, fields, archives, or post-catastrophe afterlives, we are all partaking today in the digital, the visual, and the sonic. And, we all are curating somehow.

Warburg’s practices of unmooring provenance and recurrences, and of interjecting, have been generative in visual, memory, and digital studies. He followed his iconoclastic, anti-historicist professor, Karl Lamprecht, in seeking not historical precision, but philosophical and comparative combinations and transcultural studies of collective psychologies and images for what I call patches of time (epochs). Warburg’s ideas, very influential in gallery and museum contexts today, have much potential for anthropologists, teachers, and historians. Whether we are engaging with memories, fields, archives, or post-catastrophe afterlives, we are all partaking today in the digital, the visual, and the sonic. And we all are curating somehow.

Nachleben, therefore, shifts the emphasis away from context and context-based afterlives. And Warburg’s methods open up the curatorial as politics, history, and engagement, showing the merits of the aleatory and time scrambled.

Conclusion

Afterlives go with history, with one or more pasts and their reworkings or durations, as in remembrances, images, or spots of time. Memory often motivates both scholars and subjects. Some afterlives evoke and use images, things, or remains. Ruination, whether from slow or sudden devastation, may be turned askew through afterlives of diverse modalities: lived, experienced, visual, sonic, religious, daydreamed, or with that curatorial turn that scrambles memory and time. By considering archival bits as remains and afterlives, layout techniques may come to the fore, with scholars and artists using counterpoint or a touch of chaos to position, engage, and productively skew images and texts. Historians may return to temporal devices like epochs, trajectory, duration, and sequencing to ground their histories in politics.

If some afterlives lift spirits, others motivate politics, inhibit bleakness, or beckon an audience.

Yet such interpretive techniques may be combined with afterlives as various and knotty, as packets of partial, gnarled memories. If some afterlives lift spirits, others motivate politics, inhibit bleakness, or beckon an audience. All complicate ethnography and history with their unfinished characters.

Works discussed:

Ann Stoler, ed., Imperial debris: On ruins and ruination (Duke U Press, 2013);

Ann Stoler, Duress: Imperial durabilities in our times (Duke U Press, 2016);

Nancy Rose Hunt, “Aphasia, History, and Duress,” History and Theory 58 (2019): 437-50;

Kristin Ross, May ’68 and its afterlives (Uof Chicago Press, 2002);

Nancy Rose Hunt, A nervous state: Violence, remedies and reverie in colonial Congo (Duke U Press, 2016);

Paul Wenzel Geissler, Guillaume Lachenal, John Manton, and Noémi Tousignant, eds. Traces of the future: An archaeology of medical science in Africa (Cambridge, Oslo, Paris: Intellect, 2016), with (& for quotations), Nancy Rose Hunt, “Being with Pasts: A Preface,” 9-13.

On suturing

Nancy Rose Hunt, Suturing New Medical Histories of Africa. Carl Schlettwein Lecture, no. 7 (Berlin and Zürich: LIT Verlag, 2013).

On Warburg’s ongoing sway

Felix Thurlemann, More than one picture: an art history of the hyperimage, trans. Elizabeth Tucker (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2019);

Doris McGonagill, Crisis and collection: Germany visual memory archives of the twentieth century (Würzburg : Königshausen & Neumann, 2015);

Georges Didi-Huberman, The surviving image: phantoms of time and time of phantoms: Aby Warburg’s history of art, trans. by Harvey Mendelsohn (University Park, PA : Pennsylvania State U Press, 2016).

On sound as method

Nancy Hunt, “An Acoustic Register,” in Imperial Debris, 39-66.

On the sensory, “sly poetics,” and anti-historicist “experiments with archival surfaces,”

see Nancy Rose Hunt, “History as Form, with Simmel in Tow,” History & Theory, 56 (2018): 126-144.

Most pictures by author, Nancy Rose Hunt.

Picture of Mnemosyne Atlas panels. Photo taken by dzil at the exhibition organized by OSA Archivum, Budapest. Found on Flickr, (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)