In an address to students at Indiana University in 2015, anthropologist and journalist Sarah Kendzior described Central Asian Studies as a ‘dying field’ and billed her address as a ‘eulogy’. The funding streams that had supported North American students to learn Uzbek or Dari a decade earlier were drying up; the academic landscape looked bleak; the opportunities for research—especially for long term ethnographic fieldwork—limited by difficulties of access, of training, of support, and of job-prospects in academia and beyond.

At the very moment that Kendzior was writing, however, the scholarly output on Central Asia, particularly in the fields of anthropology and history, was going through something of a growth spurt. In the early 2000s, it was possible to count published ethnographic monographs based on fieldwork in post-Soviet Central Asia on the fingers of one hand. In 2007, Maria Louw commented in the introduction to her book on Everyday Islam in Post-Soviet Central Asia on the frustrations of “conducting analysis in an anthropological no man’s land, condemned to a kind of analytical bricolage” (2007: 18) due to the dearth of anthropological analyses and theoretical arguments based on empirical material from Central Asia. A decade on, and the picture looks rather different. Not exactly a crowded field—and the institutional constraints facing scholars that Kendzior identified remain as acute as ever—but, if the rate of publication from lists such as Pittsburgh’s Central Eurasia in Context series is anything to go by, the scholarly conversation is expanding, and the ‘analytical bricolage’ engaged by anthropologists is consequently a little more nuanced, a little less frustrated and a little more playful.

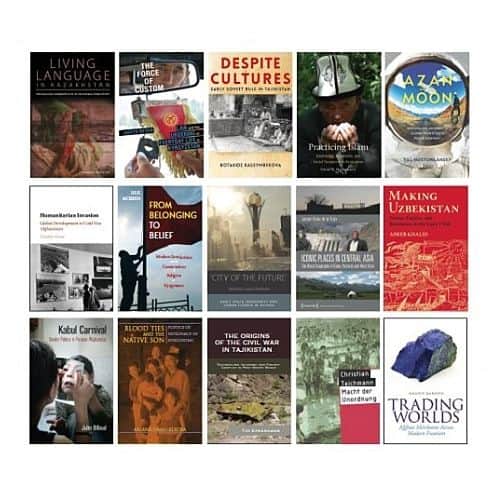

The aim of the workshop on the Future of Central Asian Studies that took place at the University of Konstanz in September 2017 was conceived in part to take stock of those shifts, by taking as its focus a discussion of fifteen monographs, in the fields of anthropology and history, published between 2016 and 2017. The format was an author-critic discussion scaled up: five panels, each featuring three new books, discussed by three readers, typically from different fields or scholarly traditions. We explicitly invited the contributors to think ‘book club’ rather than ‘debating society’: the aim being to ask what questions, research themes, paradoxes emerge from reading a particular trio of books together.

The aim of the workshop on the Future of Central Asian Studies that took place at the University of Konstanz in September 2017 was conceived in part to take stock of those shifts, by taking as its focus a discussion of fifteen monographs, in the fields of anthropology and history, published between 2016 and 2017. The format was an author-critic discussion scaled up: five panels, each featuring three new books, discussed by three readers, typically from different fields or scholarly traditions. We explicitly invited the contributors to think ‘book club’ rather than ‘debating society’: the aim being to ask what questions, research themes, paradoxes emerge from reading a particular trio of books together.

We wanted to keep the conversation open-ended, anticipating that the interesting insights emerge precisely at the point where disciplines, analytical approaches, conceptual frameworks and methodologies rub up against one another.

We pre-circulated some questions for discussion, including how we can best study Islam in Central Asia in a context of highly politicised research agendas, how ethnographic material from Central Asia can shed light on current debates in political and legal anthropology, what might be gained from drawing together historical and anthropological scholarship on law and empire, or dynamics of peace and conflict, and how the history and anthropology of Afghanistan might be incorporated more fully into the comparative study of Central Asia.

The discussions were recorded and will be made available on the Allegra website this week, grouped under the place-holder titles that we used for organisational purposes: Ordering (to be published tomorrow), Islam (to be published Wednesday), Nation (to be published Thursday), and Kinship and Belonging (to be published Friday). In each case the discussion, as we anticipated, spilled far beyond those topics, often eliciting impassioned discussion on the conditions of scholarly knowledge production themselves. There was also a more experimental aim to the format, informed by our critical reflections on the shape of the contemporary accelerated academy and the forms of institutionalised precarity that it generates.

The academic environment in which we find ourselves is one in which we are continually required not only to audit our pasts but to wager our future productivity, often as a contractual requirement of our employer (What book will you write? Which grants will you apply for? What is your Five Year Plan?) This model of academic future-proofing privileges a particular conception of academic production in which the scholar-star thrusts her (or more typically, his) intellect over a scholarly terrain to be conquered and transformed. The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NOW) actually uses ‘veni-vidi-vici’ as titles for different tiers of research grant corresponding to levels of scholarly seniority. The younger researcher merely ‘sees’; the established scholar ‘conquers’. Such models of academic audit leave little space for scholarly serendipity, for the collaborative co-production of ideas, or for the forms of emergent enquiry that aren’t open to prediction or prescription. It certainly doesn’t leave much space for taking-stock and reflecting on what productive tensions might emerge when we engage in a close, thoughtful reading of what has just been published. We wanted a workshop format that worked a little differently.

By setting ourselves no agenda other than a close discussion of recent books, we explicitly sought to engage in a form of ‘slow scholarship’ in which we could think through the tensions that emerge when different approaches are held together in conversation.

This format allowed for fascinating discussions about language, truth and the Soviet archive; about temporality and conflicting narratives of transformation; about the material qualities of water and soil, and the difference they make to anthropologies of space; about institutions and personalities and whether early Soviet Central Asia should be considered an ‘empire’; about how fieldsites change and stay the same, when people we know have had the lives turned upside down by inter-communal violence. If there was plenty of sober reflection on the conditions that prompted Kendzior’s eulogy—declining archival access; over-zealous security services, the politicisation of research agendas; the marginalisation of Central Asia within institutional research priorities—the format also allowed for a celebration of sorts: that these books exist, despite the often-precarious conditions of their scholarly production, and that their appearance within a year of each other marks a watershed moment in the consolidation of a scholarly field.

This week, enjoy one new video from the workshop each day, starting with “Ordering” (Tuesday), “Nation” (Wednesday), “Islam” (Thursday) and concluding with “Kinship and Belonging” (Friday).

I am genuinely excited to see the videos from the workshop. Much of what you are saying here resonates very strongly with me, and it outlines the frustrations that pushed me to move on from “Central Asian studies” per se years ago. That new methodological playfulness described here, I’m afraid, seems to come from within a feeling of precariousness and disillusionment with preexisting structures for funding and licensing research — there’s a freedom in it. But that might just be me. Thanks for putting this together, and for sharing the videos!