Afghanistan’s Presidential elections were scheduled to coincide with the withdrawal of U.S. and foreign troops and Afghanistan’s first democratic transfer of power. The first round on 5 April resulted in two frontrunners, the ethnic Tajik Abdullah Abdullah with 45 per cent of the ballots, and the Pashtun Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai with 31.5 per cent. Because neither candidate secured over 50%, a second round was scheduled for 14 June, to be followed by the announcement of the new President on 22 July.

The run-up to the first round resulted in eight candidates, and a reshuffling of political and military alignments. Some groups split themselves between support for Abdullah or for Ghani—former mujahideen leaders Sayyaf and Hekmatyar being two cases in point. Ghani appointed his vice Presidential candidate the notorious Uzbek warlord, General Dostum. This occurred amidst a resilient Taliban insurgency as 51,000 US-led combat troops were scheduled to leave Afghanistan, and disputes between lawmakers over the complete withdrawal of forces by 2017. The Taliban boycotted the elections. They opposed Abdullah because he agreed to sign bilateral security agreements for U.S troops to stay beyond 2014 (Ghani also agreed to sign), with Pakistan over the disputed Durand Line border, and for promoting a Persian-speaking minority elite largely alien to Afghanistan’s Pashtun majority. They opposed any peace process unless they could hold talks with any new government, a proposal Obama refused.

After the second round put Ghani ahead with 56.4% (Abdullah 43.5%), hundreds of serious fraud allegations were lodged.

In many districts, including Kabul, no ballot papers arrived. Children boosted votes in many areas. On election day, hundreds of uploads of violence and irregularities were posted online. These showed children shot dead, people with fingers cut off, private militias at large, and Afghan National police officers struggling to keep control. Abdullah threatened to establish a parallel government if the fraudulent votes were not withdrawn.

Although by 7July both parties had agreed on identifying illegitimate votes, the next day Abdullah declared himself the winner in an emotional speech to supporters. On 11 July US Secretary of State John Kerry visited Kabul and threatened to withdraw US aid if both candidates did not endorse a UN proposal to audit 8000 polling stations. They agreed.

Violence, security incidents, and killings increased throughout July. They delayed the vote audit, and the announcement of the new President. On 5 July around 400 fuel tankers were burnt at a logistics compound in Paghman district in Kabul, targeted by the Taliban because they supplied foreign troops. On 15th around 100 people died in a suicide attack in Paktika, a Taliban stronghold. The Taliban claimed it was a retaliatory attack by Abdullah’s men following his election defeat there. 17 July saw a five hour assault on Kabul airport. Washington expressed concern. On 29thKarzai’s cousin was killed at his home in Kandahar.

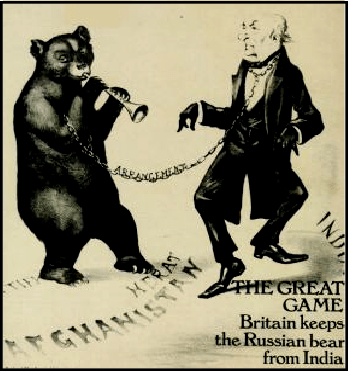

I conduct research with Afghan migrants in the UK and Pakistan. Many drew inevitable comparisons with the nineteenth-century Great Game, when Britain fought the Russian Bear in Afghanistan at the frontier of the Raj; a conflict revisited in the Soviet-Afghan war (1977-88). Given Russia’s annexation of Crimea this March, Russia’s subsequent incursions into Ukraine, and Putin’s refusal to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty, such comparisons seemed prescient.

Abdullah was an erstwhile commander of Ahmed Shah Massoud (‘The Lion of Panjshir’) in the Soviet war. Massoud fought Soviet forces, he also allied with them against U.S supported groups such as Hekmatyar’s Hizb-e-Islami, and subsequently the Taliban. Abdullah has nurtured strong connections with Russia. As Russian looked stronger in Ukraine, the US eased pressure on the Taliban; when Russia’s position weakened in Ukraine, it toughened its stance. The US is wary of a strong Afghan-Russian connection. If Russia has power in Ukraine, it is less likely to support a pro-Russian Abdullah. Identifying boundaries between ‘two’ sides is difficult when there much switching sides, including by the national police, and Abdullah supports Russia and the US. This complicates the traditional conflict between the orthodoxies of modernism and fundamentalism, expressed in the apothegm of a choice between kalam ow kalashnikov (the gun or the pen).

My interlocutor Nawroz frustratedly complained: ‘If Abdullah is the gun, and Ghani the pen, in reality they are friends. Neither is working for Afghanistan.

The Cold War ended in 1989. Now Russia is politically interested in former USSR countries, not Afghanistan, and economically in East Asia. Afghanistan’s big investor is China. China has invested in copper mines and oil fields- and built infrastructure. They did the same in almost every developing country, and massively in neighbouring Pakistan. They have maintained political distance for fear of retaliation from the Taliban, and of inciting China’s Muslim minority. A pressing issue is security. What will the Chinese government do if a warlord approaches one of its large mines demanding a bribe; then another; then the Taliban? Send troops? Target local leaders? These are big issues. In Pakistan, Chinese investments are safer because they use their own police and army officers. Would this be acceptable in Afghanistan? These days security is increasingly handed to private contractors, with terrible results.

Another major player is India, with strategic goals to create a strong buffer for relations with Pakistan. Pakistan traditionally supported the Afghan Taliban, although the killing of Pakistani forces in Kunduz in 2001 initiated the break-up Afghan and Pakistani Taliban groups, and the Taliban has posed domestic problems for Pakistan. Otherwise, the US is clearly opting out. Afghanistan has been a drain. The USA prefers Myanmar, Korea and Taiwan—where there are trade, finance, skills, and markets to win. It will retain troops to contain attempts by Iran to expand its regional or military influence. Britain has little interest. Britain’s foreign policy is to attract investments at home.

Unlike when the Taliban destroyed the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001, the 2008 Chinese contract to develop a copper mine on Mes Aynak, one of the largest archaeological sites for Buddhist artefacts in Central Asia, passed relatively unnoticed.

August began with violent protests at the IEC’s recount method, causing delays. On 7th John Kerry returned to Kabul. Both sides agreed to collaborate in a ‘National Unity government’, in which the ‘loser’ will assume the post of chief executive. On 3 September pro-Abdullah governors threatened to establish a parallel government if Abdullah lost. The 2014 NATO summit began without a new President, but a commitment to continue NATO’s ‘Enduring Partnership with Afghanistan’. The recount ended on 5 September, with Ghani ahead. Ghani looks set to assume Presidency of the ‘unity government’. Ghani has a Phd in Anthropology from Colombia University, worked for the World Bank, the UN, and Western universities.

Many perceive democracy as an alternative violence, and the new ‘American’ government the result of intervention following this summer’s violence.

Thus, violence works: not in achieving the institution of democracy (which would involve Taliban representation), but in forcing the redistribution of power in violent, perceptibly just terms that are far from transformative, but deeply conventional.

Additionally, it is unclear how much support Ghani has amongst Afghanistan’s Pashtuns (the Taliban aside, whose ‘resurgence’ may be weaker than they claim)—other than an ethnic choice over the Tajik Abdullah. Governing Afghanistan will require the acumen to appease or co-opt the warlords’ power, strengthen parliament whilst stemming corruption, and ensure Afghanistan’s interests alongside those of India, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, the US and China.