To close our thematic week on the anthropology of the state, we re-publish (with the permission of the author) this excerpt from Yael Navaro-Yashin’s last book “The Make-Believe Space”, (Duke University Press, 2012). If we decide to end our discussion on the ‘state’ with a text discussing ruins and borders, it is precisely because we sought to explore in this week the productive tensions in anthropology between those seeking to grasp the state by examining it ‘at work’ (Bierschenk and de Sardan 2014), and those who argue that the ‘state’ is perhaps better captured in its margins rather than its supposedly transparent and rational bureaucratic forms (Das and Poole 2004) — though as the books up for review show, these approaches aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive but rather a testament to the breadth and creativity of anthropological analysis.

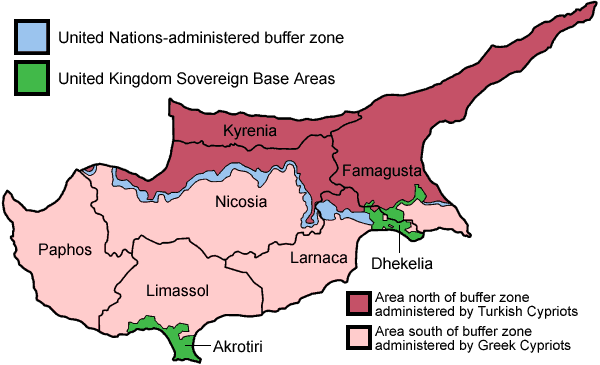

In this piece, Navaro-Yashin wanders along the border that separates the Greek and the Turkish sides of Cyprus. While providing an affective geography of a post-war setting, she highlights the ‘abjected quality’ of space in a place where international narratives of ‘liberation’ produce the actual experience of immobility, confinement, and entrapment’ (Navaro-Yashin 2003).

IN 1999, WHEN THE BORDER with the Greek side was still closed, I spent time, lingered, walked, sat, and spoke with people who lived along the border (the Green Line) on the northern side of Lefkosa (Lefkosia, Nicosia). Rust had infested any metal surface along the border that ran through neighborhoods and streets, as well as houses. Apartment blocks facing the Greek side were covered with bullet holes. Old buildings lay abandoned by their owners, with bushes, grass, and trees emerging through broken windowsills and growing out of collapsed rooftops. Old craftsmen’s shops were locked with rusty shutters. Red-colored signposts of a soldier with a gun reading ‘‘Forbidden, No Access, No Photography’’ stood in the middle of every street leading out of the central marketplace (arasta).

IN 1999, WHEN THE BORDER with the Greek side was still closed, I spent time, lingered, walked, sat, and spoke with people who lived along the border (the Green Line) on the northern side of Lefkosa (Lefkosia, Nicosia). Rust had infested any metal surface along the border that ran through neighborhoods and streets, as well as houses. Apartment blocks facing the Greek side were covered with bullet holes. Old buildings lay abandoned by their owners, with bushes, grass, and trees emerging through broken windowsills and growing out of collapsed rooftops. Old craftsmen’s shops were locked with rusty shutters. Red-colored signposts of a soldier with a gun reading ‘‘Forbidden, No Access, No Photography’’ stood in the middle of every street leading out of the central marketplace (arasta).

There were few people around: old folks whose families had moved outside the walled city (surlar içi) and workers and their families who had recently migrated from Turkey. The middle-class Turkish, Greek, and Armenian-Cypriots who once inhabited these quarters were nowhere to be seen. The border area was full of items thrown aside, things left behind, rubbish rotting away, and abandoned old objects.

On many occasions, while walking alongside the convoluted border area, zigzagging through and around bisected streets, I recorded lists of every item I could see. One of my lists reads:

- a rusty fire escape, connecting two stories of an old house a plastic water bottle, flattened and thrown aside

- children’s drawings on the wall separating the Turkish side from the United Nations ceasefire zone

- a thin black cat

- the half-erect side wall of a ruined old building of yellow stone a semi-burnt pine tree

- spilled piles of garbage

- a used tire lying on the ground

- an old oven filled with used newspapers

- the skeleton of a building, with a collapsed roof-top, broken windows, and no windowsills

- a dirty blanket lying on the side of the road dog shit

- rusty paint tins broken pieces of wood a dusty old shoe

- clothes hanging over an electric wire red car parts

- the license plate of an old car

- bullet holes on the side walls of buildings the rusty skeleton of an old pushchair an old mattress, with inside turned out broken beer bottles on the ground

- a semi-broken old wooden balcony

- basil leaves growing inside a tomato paste tin

My list goes on, a record of every thing that I could touch, smell, and see. The border was full of rubbish, debris left behind from the war and the political stalemate that followed. What was deemed useful was taken and stored or sold. The remainder was abandoned. Here one could draw an itinerary of leftovers or collect war memorabilia. Rust and dust covered every surface.

Few people walked by; even fewer lived there—certainly very few Turkish-Cypriots, and among them mostly the very elderly. Occasionally, one heard the noise of a car passing by or of the children of immigrants from Turkey playing ball in the neighboring streets. Ruined old buildings left behind by Armenian, Turkish, or Greek-Cypriots were now inhabited by workers from Turkey who had come to northern Cyprus, sometimes with their families, in search of menial jobs. On Sunday mornings, one heard the chime of church bells from the Greek side. The skeletal remains of an Armenian church, with its icons ripped away, windows broken, and marble stones demolished, sat quietly in this once mixed Armenian and Turkish-Cypriot neighborhood. Piles of litter and refuse had been left next door.

Few people walked by; even fewer lived there—certainly very few Turkish-Cypriots, and among them mostly the very elderly. Occasionally, one heard the noise of a car passing by or of the children of immigrants from Turkey playing ball in the neighboring streets. Ruined old buildings left behind by Armenian, Turkish, or Greek-Cypriots were now inhabited by workers from Turkey who had come to northern Cyprus, sometimes with their families, in search of menial jobs. On Sunday mornings, one heard the chime of church bells from the Greek side. The skeletal remains of an Armenian church, with its icons ripped away, windows broken, and marble stones demolished, sat quietly in this once mixed Armenian and Turkish-Cypriot neighborhood. Piles of litter and refuse had been left next door.

As I spent time in these spaces and lingered in these surroundings, day in and day out, I experienced a sense of eeriness that spoke through the ruins. Every piece of debris seemed uncanny. It was as if the broken walls, the wrecks of buildings, and the bullet holes had been halted midway in speech; as if they had been stunted, retaining waves of emotion inside them, ready to explode if scratched.

The space transmitted an energy of its own, which went through my body. I felt uneasy, disturbed, out of place.

As I walked through these spaces and wrote my notes, I wondered how the old ladies who lived along the border felt about the ruins. Or the immigrants from Turkey who had settled next door. And the Turkish-Cypriots, who had mostly moved out of the walled city of Lefkosa into newly built middle-class neighborhoods and suburbs. Did this space feel as uncanny to them as it did to me? ‘‘We have gotten used to this,’’ said an old Turkish-Cypriot woman living in the border area. ‘‘No, these ruins don’t disturb me.’’ ‘‘I used to feel awful walking by the ransacked Armenian church,’’ said a Turkish-Cypriot man in his late twenties who lived outside the walled city, away from the border area. ‘‘But crossing by to go to work every day, I no longer notice.’’ How could this debris not hurt?, I wondered. How could it seem normal? To me the wrecks of the buildings, the walls, and the piles of rubbish seemed so alive, as if they silently spoke their secret memories.

Affect and Politics

(…) In the psycho-analytic literature, affect has predominantly been associated with subjectivity or the self. Or, the inner world (the unconscious) of the individual has been conceptualized as the kernel through which energy is discharged. For example, the French psychoanalyst André Green argues that ‘‘the affect refers to subjective quality.’’∞ Here, affect is conceptualized as an energy that emerges from, and is therefore qualified by, a person’s subjectivity. For something to be called ‘‘affect,’’ Green argues, it has to be bound up in the coils of the subjective world, the inner world of the person. Or it is the subjective world that gives a quality to cathectic energy, therefore enabling us to interpret it as ‘‘affect.’’

(…)

In contrast to this position, let us consider cultural constructionist work on the emotions as developed by anthropologists. In this reading, affect and the emotions are studied under the same rubric (as referring to the same thing) and as a cultural phenomenon. Accordingly, the emotions are culturally constituted, understood, interpreted, managed, and framed. They are contingent and contextual. Numerous ethnographies have been written in this vein, studying the culturally attuned meanings of specific emotions. Many of these studies have taken language as a conveyor of emotional experience and, therefore, as the representation of ‘‘culture.’’ In its critique of psychoanalysis (read as a Eurocentric discourse and practice), this body of anthropological literature has brought to light non-Western discourses about the emotions. And yet, while human beings are studied fundamentally as cultural beings, they nevertheless remain, in works in this vein, the main agents (or originators) of affective energy (…).

To be considered alongside this literature, is the long tradition of studying affect and politics in European social theory, particularly critical theory coming out of the Frankfurt School. In works by Theodor Adorno, Elias Canetti, and others, we see a fascination with the political figure of the crowd, the masses, or the mob. Developing a theory of fascism by engaging with Freud’s essay Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, Adorno sees in the masses a sinister potential for worshipping the father figure, the leader. Such works, emerging out of wartime Europe, have placed affect firmly within the domain of the public sphere, enabling us to now study affect as a political and politically generated phenomenon. Yet in these works, ‘‘politics’’ or ‘‘the political’’ is imagined as a broader category of ‘‘the person’’—as a crowd, if you will, of human beings. The idea is that when people are massed together as a group, a different kind of energy is projected: Their individuality goes amiss, and they are pulled or directed toward aims or projects in which, if left alone, they would not have gotten involved.

Indeed, in this literature inspired by Freud (and Marx), the individual is the main psychical and political agent because the social and the political are conceived as the individual writ large.

More recent work on affect and politics has challenged old associations between the emotions and the private sphere. Building on a long tradition of feminist theory, literary scholars such as Lauren Berlant and Glenn Hendler have studied what they call ‘‘public sentiments.’’ They have convincingly argued that, far from being ‘‘personal’’ phenomena, having to do with the privacy of the individual, the emotions are always and already public and political. Studying American novels of the nineteenth century, Hendler argues that sentiments such as sympathy were politically and pedagogically inculcated. Berlant has produced a similar analysis of compassion. The contribution of this work (…) is to illustrate the ways in which the public sphere is a source of affect. Yet as in critical theory’s imaginings of the political, here, too, politics is conceptualized first and foremost as a sphere of human or intersubjective action and interaction.

I propose, (…), to treat affect and politics in a new light, where neither affect nor politics is a singularly human (or subjective) phenomenon. (…) I trace not so much how affect is employed or produced politically as how it is generated out of interactions with spaces and materialities—in this case, a postwar environment. I study war debris, abandoned buildings, looted objects, leftovers, ruins, the border, and the decaying environment of Lefkosa as spaces and objects that, retaining memories of a political history and specific policies, evoke special kinds of affect among the people who live there. I am interested in how political debris—here, the remains of war—generates conflicted and complex affectivities.

I argue that affect is to be researched not only as pertaining to or emerging out of human subjectivity (or the self), but also as engendered out of political engagements with space and entanglements in materialities.

In The Transmission of Affect, Teresa Brennan writes:

Any inquiry into how one feels the other’s affects, or the ‘‘atmosphere,’’ has to take account of physiology as well as the social, psychological factors that generated the atmosphere in the first place. The transmission of affect, whether it is grief, anxiety, or anger, is social or psychological in origin. But the transmission is also responsible for bodily changes; some are brief changes, as in a whiff of the room’s atmosphere, some longer lasting. In other words, the transmission of affect, if only for an instant, alters the biochemistry and neurology of the subject. The ‘‘atmosphere’’ or the environment literally gets into the individual. Physically and biologically, something is present that was not there before, but it did not originate sui generis: it was not generated solely or sometimes even in part by the individual organism or its genes.

Dealing with the kinds of objections that her propositions provoke, Brennan writes, ‘‘We are particularly resistant to the idea that our emotions are not altogether our own,’’ and goes on to critique what she calls the Eurocentric notion of the ‘‘emotionally contained subject.’’ Her very use of the term ‘‘transmission’’ for a theory of affect encourages the imagination of more fluid boundaries, flow, and passages between individuals (intersubjectively), as well as between human beings and the environment. She writes:

I am using the term ‘‘transmission of affect’’ to capture a process that is social in origin but biological and physical in effect. The origin of transmitted affects is social in that these affects do not only arise within a particular person but also come from without. They come via an interaction with other people and an environment. But they have a physiological impact. By the transmission of affect, I mean simply that the emotions or affects of one person, and the enhancing or depressing energies these affects entail, can enter into another. A definition of affect as such is more complicated.

In this interpretation, the reference points for affect are not to be found within the individual or her subjectivity and inner world alone. Instead, affect, almost like mercury, is an energy of sorts, on the move, one that knows no bounds—hence, the metaphor of ‘‘transmission.’’

However, having charted the terrain for studying energies transmitted through the atmosphere, muddling the boundaries between the individual and the environment, Brennan then focuses the rest of her study on the transmission of affect intersubjectively, or between individuals. In so doing, she returns to an old question in the psychoanalytic literature on transference and counter-transference and leaves aside what is to me the more interesting (and certainly less studied) field of interactions between the person and her or his environment. She writes: ‘‘Visitors to New York City or Delphi testify happily to the energy that comes out of the pavement in the one and the ancient peace of the other. But investigating environmental factors such as these falls outside the scope of this book. This initial investigation is limited to the transmission of affect and energy between and among human subjects.’’ I explore precisely the terrain that Brennan left aside, that feeling discharged by the environment or produced through an interaction between human beings and their material surroundings.

Bordering Ruins, Living with Rubbish

Two soldiers wait on duty, under a tree, to protect themselves from the piercing sun. I park my car in the shade and walk into the walled city of Lefkosa through a small alleyway. I see a house with an Ottoman numeric inscription, indicating it was built in 1919. The paint on the door has peeled off, and the house is locked. Through the half-broken shutters, I notice that the house has lost its glass windows. Peeking through, I see a pink plastic wash basin. A small blond child, without shoes, sits on the front steps at the entrance to the house. I learn that he is called Turgay. Does anybody live here? I ask. He says yes.

Many contemporary residents of the walled city of Lefkosa live in such spaces, immigrants from Turkey who have settled with the hope of finding jobs, as well as old people left behind by their children. Half-torn mattresses, eaten by moths, have been covered with cardboard paper. Patched pieces of cloth have been hung to dry over old, limping Ottoman-style sofas. A plastic sieve here; a wooden spoon there—utensils found here and there have been combined to create a new life. One bottomless chair with torn matting on one side; a worn-out sofa on the other. An old woman pulls a big sack of personal odds and ends with a string behind her on the ground. In her bundle are her belongings—a woolen bed cover, a towel, a pot, a pan—all tied up tightly together with strings.

I walk a little farther and reach the border area again. An open space, right beside the border, has been turned into a garbage dump. Bones of recently butchered animals lie on the ground, covered with flies. Watermelon husks and other food remains, plastic bags, bottles, and cans are all scattered about. I make my way through half-eaten figs and crushed tomatoes to reach the other side of the road.

In front of a house right along the border, two women sit, cutting red peppers to dry under the sun. I approach the house, which is leaning to one side from structural damage. One of the women warns me to come no farther, saying, ‘‘This is the border.’’ She also volunteers her opinion on the border. ‘‘In fact,’’ she says, ‘‘to tell you the truth, they don’t do us any harm. We hear no sound from the other side. But it is our people, the ones on this side, who hurt us. The other day, they wanted to throw us out of this house.’’ I ask the woman where she is from. She tells me her story of arriving in northern Cyprus from Hatay in southern Turkey, from a village that borders Syria. She tells me how her main problems are with her Turkish-Cypriot landlords and employers.

Then, seeing that I am curious about the border, she says: ‘‘Have you climbed to the top of that building? You can see the other side well from there.’’

I walk to the block of apartments next door. The empty-looking building does not appear very solid as I climb it. It is a structure from the 1960s, abandoned to its fate. But I notice that some apartments have inhabitants. Mud and dust have grown on the steps leading to the top floor. To my amazement, the entire top floor remains as it was in the days of war, as a shooting point. Sacks of sand were placed on top of one another to hide and protect the soldiers. Through decades of ceasefire, no one had removed the sand sacks.

I speak with an old Turkish-Cypriot man who lives with his wife in a house very close to the border. His children, now grown up, have moved out of the area and to the suburbs. ‘‘A shroud (kefen) has been draped over Lefkosa,’’ he says. ‘‘Lefkosa is now deceased (Lefko¸sa ölmü¸stür).’’

The Make-Believe Space. Yael Navaro-Yashin, pp. 129-160. Copyright, 2012, Duke University Press. All rights reserved. Republished by permission of the copyright holder.

References cited

Das, Veena, and Deborah Poole. 2004. Anthropology in the Margins of the State. School of American Research Press. Santa Fe

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2003. “`Life Is Dead Here’ Sensing the Political in `no Man’s Land’.” Anthropological Theory 3 (1) (March 1): 107–125.

This post was first published on 2 June 2015.