This post is part of our Encountering Precarities series. The thematic thread engages with the multiple and asymmetrical forms of precarisation and vulnerabilisation involving both ethnographers and their interlocutors in and beyond the field.

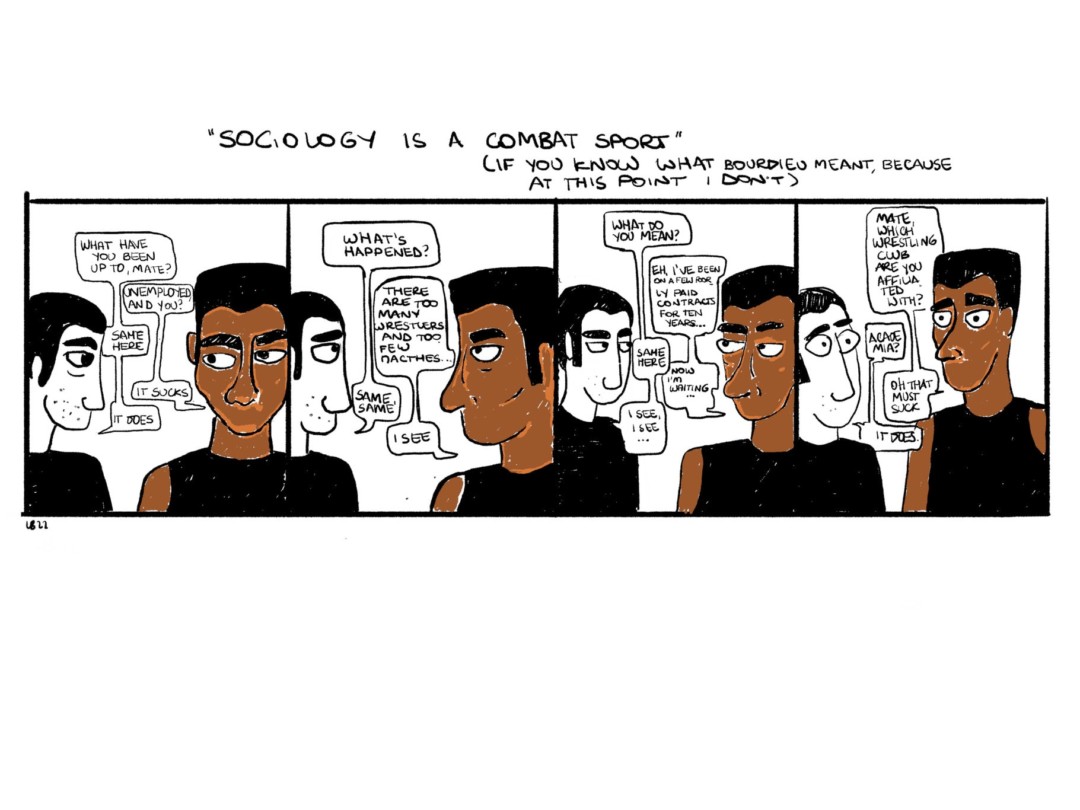

“Sociology is a combat sport”, Pierre Bourdieu famously said. While he was pointing to the social sciences’ usefulness as a tool of self-defence against the naturalization of social arbitrariness, I’ll take Bourdieu’s sentence more literally by sketching a comparison between precariously employed scholars and young Senegalese wrestlers. Mine is a provocative stance. The differences between academic work and làmb (Senegalese wrestling with punches) are so evident that this could not be more than a mock comparison. Làmb is a stand-up form of wrestling that combines both grappling and punching techniques, in which the victory is obtained by throwing his opponent on the ground; occasionally academia can be home to harsh disputes and hard competition but no contest is won by K.O (at least literally). Nevertheless, even in (or by) its very oddity, I hope this comparison can be productive. Two intersecting critical questions drive my experiment: Can viewing the situation of precariously employed anthropologists through the lens of làmb can cast new light on this precarisation? Does this change of perspective suggest strategies to engage with a precarity that is partially shared with our interlocutors?

This comparative experimentation is meant to de-centre academia as a source of superior knowledge: it foregrounds what we can learn practically about our own situation, predicaments and politics from our interactants in the field. In so doing, I hope, we can eventually find new paths to re-launch anthropology’s long held striving to foster social justice.

For ten months I participated in the daily training and the activities of a écurie in Dakar (écurie is French for stable and refers to the sporting associations where wrestling training takes place). I shared viscerally some of the joys and hardships of wrestling in Dakar; I made friends among teammates; I learned about the troubled history of the integration of Senegal (and Africa) in world capitalism and the position of the “ghetto” (i.e. the most wretched zones of the Dakar’s banlieue) youth in Senegalese society. During fieldwork, I reflected upon shared predicaments with my interlocutors as I have been trying to carve the space for a political alliance. It was not and it is not an easy task. Even if this could be a start in order to establish “thick solidarity” (Liu, Shange 2018), it is not enough for implementing politically efficacious actions, in part because the causes and features of precarity in academia and in Dakar’s outskirts are clearly not the same.

Certainly, wage imbalances in academia are less strident than in làmb – considering that the cachet of a wrestling star is almost one thousand times higher than that of a not-yet-famous wrestler.

Partially shared precarity

Apart from undergoing a similar process of neoliberalization and commoditization, làmb and academia have very little in common: from theirs spaces (sandy arenas versus tidy classrooms), to social locations of their actors (young black boys coming from Senegal´s marginalized areas versus prevalently white middle and upper class people), to tasks involved (a rough and physically exerting craft versus an apparently polite and bodily gentle occupation) and their relationship with world historical processes, differences are striking. Not to mention the difference in the disciplining techniques involved: while even in làmb, charts, scores and rankings are spreading, we are very far away from the auditing procedures that haunt academia (Brenneis, Shore, Wright 2005). Moreover, while the great majority of Senegalese wrestlers identify themselves as men, in academia the worst conditions of precarity affect a higher percentage of women than men –though there are differences with regards to countries and regions (Fotta, Ivancheva, Pernes 2020; Cultural Anthropology 2018; Palumbo 2018). And last but not least, while làmb is a national sport in Senegal that attracts high popular and political attention (Chevé et al. 2014), academic work rarely reaches a wide audience – and this is the case for anthropological studies especially (Erikson 2006). Though some academic studies (in STEM and especially economy) have strong political influence, anthropology tends to be marginalised in dominant political and economic circles that increasingly demand quantitative and uncommitted “truths” (Herzfeld 2018).

Nevertheless, as I strive to advance as a precarious scholar some of my predicaments are reminiscent of those of my wrestler friends in Dakar. As I struggle to find a way to make ends meet – navigating between writing papers, filling applications and fixed-term jobs – my tribulations and the difficulties of making a livelihood while trying to build a career as a young wrestler in Dakar cease to seem incommensurable. At least, in làmb just as in academia, self-entrepreneurial attitudes are widespread and their disciplining effects in putting on the shoulders of the individual subject the exclusive responsibility of both success and failure are not so dissimilar (Hann 2018). Moreover, the làmb world is riven by stark economic imbalances, not so far away from those that you can find in academia. The world of làmb is populated by: a handful of prosperous promoter and top mangers, a tiny minority of revered wrestling stars, a few relatively successful champions, some promising young fighters, and a vast majority of almost unknown and poorly paid wrestlers (Bonhomme 2022). These last often spent more money for the preparation of their bouts than they receive, hoping that the sacrifices of today will be the glory of tomorrow, despite the fact that only very few of them will succeed (Besnier et al. 2018). Certainly, wage imbalances in academia are less strident than in làmb – considering that the cachet of a wrestling star is almost one thousand times higher than that of a not-yet-famous wrestler. Actually, the percentage of “middle range” incomes is higher in academia than in làmb, even considering the large pool of poorly paid adjuncts and unpaid graduate students who perform teaching and service work. Nevertheless, in neoliberal times some changes in the political economy of knowledge and in research funding have produced a cruel coupling between increasing precarisation for many and rising prestige for few. A situation that drove some authors to compare the Principal Investigators of externally funded projects to football stars – a select few, which are paired with a large pool of precariously employed scholars, sometimes working under exploitative labour conditions and unable to build stable living situations (Tilche, Loperfido 2019).

Awkward connections

Yet unexpected connections don’t stop here; other similarities are perhaps even more striking. It is suggestive that in order to thrive in wrestling you must be strong both on a sporting and on a “magical-religious” basis. Similarly, to get a permanent position in anthropology you must possess scholarly abilities, but a degree from a prestigious institution can work almost like an efficacious talisman (Kawa et al. 2018), and to be in the right place at the right time can make all the difference. Some analyses of the Italian academic field of anthropology, for example, have shown the power of “the genius loci principle” (i.e. local affiliation to the University advertising the position) in determining the outcomes of the public competitions for research and teaching appointments (Moss 2012; Palumbo 2018). Given the fragmentation of the field, the lack of unambiguously agreed standards to asses merit, the selection rules that render the evaluation of the candidates difficult, this was not necessarily an index of straightforward corruption or nepotism, and paradoxically sometimes forms of patronage worked to reward (locally-recognised) merit (Moss 2012). Anyway, to get a job as an anthropologist in an Italian university you need backing from the right people, in almost the same way as to win bouts in làmb you need the help of powerful marabouts (magical-religious experts that are supposed to ensure the success and well being of their clients by working through the “invisible domain”).

Photo courtesy of the author.

Wrestlers like academics have to carefully manage their public image, being constantly under evaluation and ready to face changing situations, at the same time trying to protect themselves against evil tongues. In làmb as in academia, while the gulf between demand (big matches and permanent positions) and supply (the number of would-be wrestling tenors and tenured professors) widens, the tensions between mutualistic values and individualistic drives increase. In stiffening competition for scarce resources, this imbalance tends to feed bitter rivalries and suspicions. As a consequence, it makes harder to sustain each other and to collaborate toward shared goals – fearing that someone might exploit the common platform for personal aims. All this contributes to render both domains stressful and life consuming, haunted by insecurities and unfairness. In this vein, even if a literal juxtaposition between witchcraft’s crisis and labour burn-out is methodologically untenable, reflecting on how high-performance imperatives coupled with the perception of being constantly under scrutiny, and potentially also under attack, is detrimental to health’s conditions is crucial.

Arenas of struggle

Viewing the situations of precariously employed scholars through the lens of làmb can help to highlight some systematic ills; namely, how total competition and struggle for position and reputation in the face of shrinking opportunities can easily drive to gossiping and aggression, contributing to produce toxic work environments. While this could be understandable in the world of làmb – where trying to destabilize the adversary is inscribed in the logic of competition – it seems less wise in academic contexts to transform intellectual labour into a martial art. Maybe we should constantly bear in mind how to critically engage with colleagues’ works without rendering peer-reviews, comments and evaluations into techniques to annihilate or entrap adversaries. All in all, even in làmb too high levels of competition can be detrimental, hindering the possibility to make a common front. The last time Senegalese wrestlers united going on strike to protest against a proposal to curtail cachets, was in the early 1980s. And we can suspect that the increasing neoliberalisation of this sporting milieu in the last thirty years did not help for uniting as a collective labour force. While in academia some steps forward have been made in organizing for claiming a fairer share of resources and workload, in làmb only scattered voices denounced paying imbalances – and no effective action has been made toward raising the cachets and opportunities for not-yet-famous wrestlers.

Wrestlers like academics have to carefully manage their public image, being constantly under evaluation and ready to face changing situations, at the same time trying to protect themselves against evil tongues.

Julia Eckert (2019) rightly pointed out that we must elaborate a very specific notion of academic precarity in order to put in place efficacious strategies to effect changes in universities. Only by grasping the disciplining mechanisms related to specific economic and political contexts, to “audit culture” (with its marketisation and managerialism appendages), and to funding procedures can we hope to be efficacious in acting upon the academic precariat. From a contingent and specific point of view, she is doubtless right. Nevertheless, I think that struggles against precarisation in academia should be part of a broader political agenda. I see at least three main arenas of action: first, the most specific one related to the academic field; secondly, a broader field of action concerned with the marginalisation of anthropology in public debates and policies; thirdly, the broadest field concerned with political struggles toward social justice at a transnational level. Each field requires specific actions and alliances, yet I think that we can be really efficacious only by engaging in all of the three arenas. It is by positioning the actions against precarisation in academia in this larger agenda that we can hope to find common grounds for building politically efficacious coalitions with research participants, and respond to the challenges of raising anthropology public impact. This thread’s call to reflect on the challenges and opportunities of shared precarity and on anthropology’s epistemic crisis prompts us to think and act creatively. It is clearly an ambitious and difficult task, nevertheless one that is not only timely but also needed if we want to act against the mechanisms of academic precarisation without surrendering to social and political irrelevance.

Though mine is a call to find synergies between the fights against precarisation, the marginalisation of anthropology (in public debates, in the job market and in the hierarchy of knowledge), and socio-political injustices, I’m not arguing that every anthropologist must become an activist. This is a matter that should remain predicated on personal decision. What I want to stress is that writing on academic precarity from the vantage point of the precarity (partially) shared with our research participants brings to the forefront some common predicaments that, after all, present analogies to those affecting anthropology as a whole. As public discourses that increasingly demand unquestionable and measurable truths put anthropology – a science of contingence and the messiness of practice that defies rigid quantification – to the margin (Herzfeld 2018), precariously employed and unemployed workers are those who, so to speak, do not have “the numbers”. These are people whose marginalisation is justified by the requirements of job seekers, evaluation committees and “audit culture”; people objectified as flawed and lacking in skills against the golden standard of the neoliberal self-entrepreneurial subject. From this vantage point, it is possible to argue that, in the contemporary conjuncture of neoliberal globalization, there are some elective affinities between the situation of many types of precarious workers and that of anthropology as a discipline. If it is the case, somehow anthropologists and the majority of precariously employed workers should be like “structural allies”, since the dictates of quantifiable performativity, and the obsessive quest for measurable and standardized objectivity concur to put both of them in trouble.

References:

Anthropology, Cultural, (2018) “Academic Precarity in American Anthropology: A Forum”, Member Voices, Fieldsights, May 18. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/series/academic-precarity-in-american-anthropology-a-forum

Besnier, N., et al. (2018) “Rethinking Masculinity in the Neoliberal Order: Cameroonian Footballers, Fijian Rugby Players and Senegalese Wresters”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 60 (4): 839-872.

Bonhomme, J. (2022) Le Champion du quartier. Se faire un nom dans la lutte sénégalaise, Milan: Éditions Mimésis.

Brenneis, D., Shore, C., Wright, S. (2005) “Getting the Measure of Academia: Universities and the Politics of Accountability”, Anthropology in Action, 21 (1): 1-10.

Chevé, et al. (2014) Corps en lutte. L’art du combat au Sénégal, Paris: CNRS Éditions

Eckert, J. (2019) “Undisciplining our thinking”, Social Anthropology, 27 (s2): 84-87.

Eriksen, T.H. (2006) Engaging Anthropology: The Case for a Public Presence, Oxford and New York: Berg Publishing.

Fotta, M., Ivancheva, M., Pernes, R., (2020) The anthropological career in Europe: A complete report on the EASA membership survey. European Association of Social Anthropologists.

Hann, M. (2018) “La lutte précaire: un sport de combat sénégalais à l’ère du néolibéralisme”, Corps, 16 (1): 99-109.

Herzfeld, M. (2018) “Anthropological Realism in a Scientistic Age”, Anthropological Theory, 18 (1): 129-150.

Kawa N.C. et al. (2018) “The Social Network of US Academic Anthropology and Its Inequalities”, American Anthropologist, 121 (1): 14-29.

Liu, R., Shange, S. (2018) “Toward Thick Solidarity: Theorizing Empathy in Social Justice Movements”, Radical History Review, 131 (May): 189-198.

Moss, D. (2012) “When Patronage Meets Meritocracy: Or, the Italian Academic Concorso as Cockfight”, European Journal of Sociology, 53 (2): 205-231.

Palumbo, B. (2018), Lo strabismo della DEA. Antropologia, accademia e società in Italia, Palermo: Edizioni del Museo Pasqualino.

Tilche, A., Loperfido, G. (2019), “The return of armchair anthropology? Debating the ethics and politics of big projects”, Social Anthropology, 27 (s2): 111-112.

Featured image by Letizia Bonanno.