Note from Allegra editors:

We publish this video and transcript of EASA President Mariya Ivancheva’s talk from the annual conference Why the World Needs Anthropologists of the Applied Anthropology Network (AAN) of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) in conjunction with the LeftEast collective, in which Mariya is a member. WWAN took place in Prague in September 2021, under the topic “Mobilising the Planet.” Earlier in 2021, Mariya was elected President of EASA on the PrecAnthro platform, which, like LeftEast, was also represented at the event by Matan Kaminer. PrecAnthro emerged as a result of precarious anthropologists’ determination to fight for labour rights, politicize the discipline, and push EASA to become more proactive on social justice issues. In her talk, Mariya speaks of the gradual convergence of her academic and activist work in Eastern Europe, Venezuela and South Africa. We share this video with the permission of AAN and thank Matan Kaminer for his work on the transcription of the talk.

Transcript:

Thank you very much. In preparing this talk, I realized that of the speakers, I’m probably the only one who’s going to speak about Eastern Europe. I’m starting this talk today, on the 11th of September, with the glasses of Salvador Allende, sculptured in Caracas’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs. And in a way my talk is going to be a tale of two socialisms. We can speak of today as a meaningful coincidence of this date, with the US regime’s military effort unravelling in Afghanistan; but we can also think of today as the commemoration of the 1973 coup, supported by the US, against democratic socialism in Salvador Allende’s Chile.

What I’m going to talk about, which is quite autobiographical, is also a reflection on how a scholar of activism becomes more of a scholar activist through personal experience. It’s also a call not to romanticize one or another socialist regime, which had their own weaknesses and vulnerabilities, but to remember the promises, intentions and movements that brought these experiments to being and the alternative routes history might have taken were they not crushed by capitalism.

So, I was born in Pleven but I was brought up on the Salvador Allende Boulevard in Sofia, which was later renamed after Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov. This monument on the road island was later overtaken by a business office and a betting shop and casino. I was educated in liberal public institutions in Bulgaria in the 1990s and 2000s, where the only way that you could speak about socialism was to call it ‘totalitarian’ and to deny its existence en gros, instead of thinking of what were the redemptive and the negative parts of it and what we could learn from this experience. But I was also, as many of us in those days, coming from a more theoretical background in the social sciences which led me to question the reasons for the presence or absence or deficit of civil society: “Why don’t we have a strong civil society in Eastern Europe?”. This is what later Agnes Gagyi, a Hungarian anthropologist and sociologist, and I have been speaking of in our shared and separate work about the normativity of the West in our part of the world, where this self-orientalizing view of ‘permanent backwardness’ and ‘catching up’ has also meant that we have to always think of what was lacking. This narrative still, sadly, has an aftertaste for in the West: there’s always something better, bigger, faster, and more, and it’s usually what’s happening in Spain nowadays, or what happened with Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, or Bolivia, that’s kind of more exotic and better, and very often we don’t look at what’s happening in our own contexts. And it is not because we can’t, but because this normativity is what we have been brought up with very strongly.

So my first study was actually of Czech dissidents, like Vaclav Havel. What I was really interested in was the real-life utopias of academics and intellectuals; what were their visions of a better society? One thing that i was coming to terms with, starting to study literature on socialist utopias and socialist movements, was the question of why we always speak of moments like Paris in 1968 as a kind of promise for revolution and liberation, but we very often don’t speak about Prague in ‘68 in the same way or of Hungary in ‘56 or of Poland in ‘81. I remember encountering, back in the days, Rudi Dutschke’s words to Jacques Rupnik soon before Dutschke died. He said: “In retrospect, the great event of ‘68 in Europe was not Paris but Prague, but we were unable to see this at that time”. Now, he was by no stretch of imagination an anti-communist, this I can assure you. Why was it important what was happening in Eastern Europe at that time?

What came out in the literature in the early 2000s was that the greatness of this moment was connected to the grassroots practices of civil societies in kitchens, cellars, and Flying University seminars in remote locations. They were connected to a few individuals – nowadays we think of them as if they were mostly university-educated, able-bodied white males which the West called dissidents – and this term somehow stuck. Of course, they weren’t only always male, mostly white, mostly university educated; still, those are the ones that we still have in our social memory. What I found out in my first engagement with their work was that a lot of the times they were using the tribune that Western NGOs left and right activists gave them to demand social change, and to say that they wanted to change the terms of dialogue, and to say that those most vulnerable were to be listened to (read, they were the most vulnerable), and that they were the ones who had to speak truth because they spoke out of ‘bare existence’.

A lot of the times they were using the tribune that Western NGOs left and right activists gave them to demand social change.

Of course, to do that under the pretext of ‘civil society’ is a bit contradictory if we go back to Marx. Because as we know, in Marxist terms, civil society is Burgerliche Gesellschaft, so it is first and foremost an institution enabling the protection by the state of market freedom for those who own the means of production and private property. In Eastern Europe, civil society became something else: it became society against the state, so the civility and peacefulness was linked to European civilization and modernity. As Milan Kundera said: “What is Europe if not Europe of the small nations,” ergo, Central Europe. In the same way Havel and other Czech, Hungarian and other dissidents, wherever they were even allowed, were making this claim of life in truth. And truth meant the right to speak against state-socialist power, but not the right to speak against the market. I think we have to bear this in mind for now; we will come back to it.

The next step in my journey through anthropology was to listen to what other authors had to say about civil society. Most importantly, what Partha Chatterjee had to say about civil society as an instrument of the upper class to secure its position and channel its interest through the state. Meanwhile, what he called political society is the ever-more eliminated surplus population, in constant severe crisis of social reproduction, abandoned, and for whom the only path to gain solutions to their immediate problems is violence and localized action.

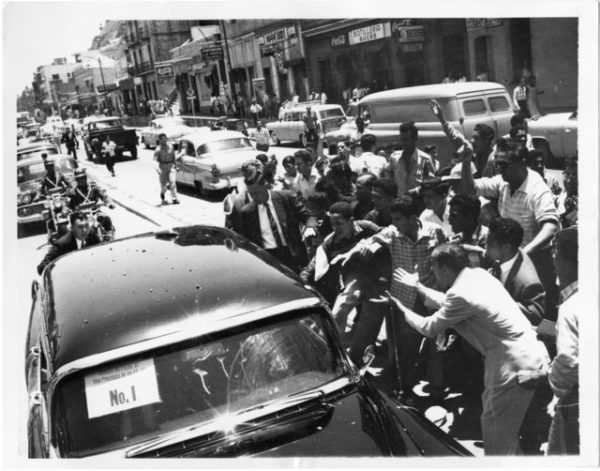

There was another 1989. It happened in Venezuela on the 27th of February 1989, days after the new election. Then in his second term [in power], Prime Minister Carlos Andres Perez signed onto the Washington Consensus, which immediately resulted in cuts to public funding. The first utility that was affected was gasoline for public use. People were angry at this more than anything, because the social contract in a petro-country is that people don’t have to pay for oil for public consumption. But it also meant that many people who were already living under the threshold of poverty could not bear it any more; so the last straw had broken the camel’s back.

These are remembered as food riots; they usually didn’t make it downtown. There was looting of shops and burning of infrastructure, blockades of means of transport in peripheral neighborhoods and barricades. They were violently smashed by the police; the dead count is still not known because there are still bodies being found in mass graves. This was called the beginning of the Fourth World War by Venezuelan intellectual Luis Brito Garcia, with the Third being the Cold War. The Fourth World War is not fought by armies; it is the wretched of the earth against the owners of the means of production and against neoliberal governance.

However, initially I did not go to Venezuela for my fieldwork because of this last story but because of the previous one I told: I was really interested to see what happens to radical intellectuals when they come to power and use the university to perform social change. The big contradiction there is, firstly, that people who have previously been anti-authoritarians have to take state power and gain recognition; but secondly, what happens to those who are proponents of egalitarian reform that challenges their privileges? That is what happens to intellectuals many times when they come to power and propose, for instance, massification of higher education.

Some take-home lessons would be, first, that the old guard of the left did not get rid of their privilege, but often transformed it into a revolutionary capital which was then used to push back any internal rectification. Then, there was also a first generation entering into higher education, who became the new educators. They gained social mobility but were all the time shamed as belonging to the new middle class. Many of them have nowadays emigrated to other Latin American countries. The third important finding for me there, which I’m still carrying along and for which I had to start reading more social reproduction theory, was that this everyday revolution was carried on the shoulders of women. Often adult learners and beneficiaries of social programs, often single mothers and workers, they did four shifts, also including political activism in different roles. This regime gave them a lot of political agency, but they were also still suffering the hangover of economic marginalization.

I came back home to Europe in 2018 with these lessons. I was coming and going, and found my own country in an immense crisis of social reproduction. In 2012-2013 Bulgaria was in a situation where the increase of electricity prices had produced an enormous tension in society. Over 15 men, mostly fathers of indebted families, committed suicide through self-immolation: they burned themselves. At the same time, there was a very strong liberal narrative that despite the fact that we could mobilize thousands for anti-corruption protests, we should not be against increased electricity fees. This was a ‘social cause’ whereas we are ‘civil’. We need to fight for civil causes, and civil causes are not economic causes, so these people who went on the streets – and there were many more waves of protests that followed for economic causes – were constantly shamed.

So I and others in Bulgarian regions, as part of a small newborn left at that point, started trying to counter this narrative. We’ve been doing that since then, and that’s why many of you know me and I know you from other activist events. But it has not been very easy, obviously. Something that comes from my previous experiences in research was that we were having to deal with a few contradictions ourselves: we were left under the shadow of a so-called totalitarian left, which had today transformed into oligarchic neo-liberal hardcore parties. We also had to be very inward-looking and to solve immense problems that were not at the scale where we were working. We had to speak about mass privatization and dismantlement of industries, agriculture and public services, and the political and economic grounds of the emerging state-capital-organized crime nexus. Then there was also mass migration of which the survival of the whole society depends, and soaring household debt and insecurity. However, a bit like the dissidents whom I discussed previously, we were having another problem in Bulgaria, while we were mourning these men who committed suicide by self-immolation.

We were facing a shortage of time between contracts, shortage of space and belonging, and lack of ability to plan ahead and think in the mid- and the long-term.

At this time many of us were not in Bulgaria, because we were caught by the western left, which for the first time recognized that we could speak at big conferences where people could recognize us as ‘really radical’. A lot of this meant reproducing the narrative of the dissidents who should be recognized by the west for whatever they were doing, and looking for recognition there as if it were going to solve some problems at home. But in the meantime, for me and for many of us, this crisis of social reproduction was coming ever closer. It was hitting closer to home, getting closer to the bone. I was finishing a PhD and beginning a precarious career in academia – which some of us [activists in the region] do in academia, others in NGO activism and so forth – and it was pushing me further afield, because there were no jobs where I [and we] wanted to be. It was also creating this difficulty to connect to others, because we were always moving around. So, I ended up, by irony of fate, at that moment in Ireland where I studied precarity in academia. I was finding out that beyond the crisis of, let’s say, representation, redistribution and recognition or respect that precarious academics were facing, we were facing a shortage of time between contracts, always trying to get into new applications; shortage of space and belonging due to the constant moving and the impossibility to mobilize ourselves, and lack of ability to plan ahead and think in the mid- and the long-term. There was a similarity to the peripherality of the Caracas riots, where you know you can’t make it to the center of power, but you try to do something locally and you burn out very quickly – and then you’re on the next contract. Of course, it’s not quite so visceral, but it was very much felt so by many of us. That is how PrecAnthro was established and here I am, brought from the periphery to the center of the European Association of Social Anthropology, of which I was just a member until recently. One thing we found through much work including a survey that we did with Martin Fotta and Raluca Pernes, was that 49 percent of EASA members are precarious anthropologists. These are the people who could pay the membership fee, so imagine the rest.

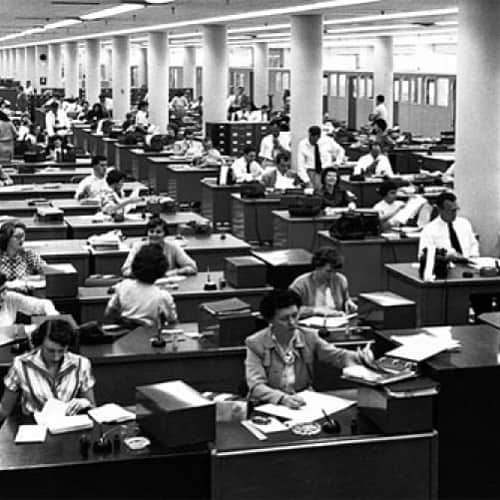

But then I was also carrying out work, you know, having to find another contract. So my next contract brought me to South Africa and the UK. I was hired – on a [fixed-term] contract again – by the University of Leeds, where I was studying the digitalization and digital disruption of higher education in South Africa and the UK. There I found a different constellation of power, different actors: there are big corporations with billion-dollar incomes that hide behind established university brands to rip off 60 to 95 percent of all profit from student fees, shaved from aspiring middle classes in the Global South while corporations in the Global North harvest and sell big data from students. There were university senior managers who gained places on advisory boards and bonuses and patted themselves on the back for being innovative, up-to-speed, and employability-driven. Then there were university-hired faculty who even before the pandemic were working under intensifying and extensifying workloads, teaching in three shifts sometimes; [they would be] doing one class online, one hybrid, and one offline, while at the same time doing some courses for university and public-private partnerships that they didn’t even know were being sold by the private company for money that the private company gets back. At the same time, having to chase research income and publications to keep up the prestige that attracts fee-paying students; increasingly, many were hired sessionally under always more unbundled and obscure contract names like “digital content curator,” “digital curriculum developer,” or “MOOC forum moderator.”

This is a class war, and this is a war that we have to fight together; we’re not in a golden cage that is just based on merit, where we can proceed into an academic career without having to not just face this reality but live it with our own skin.

That’s not even the worst part for us faculty, because there is also a reserve army of faculty who are not even hired by universities but by the same private companies. I worked for two years at the University of Liverpool, and 80 percent of my colleagues were hired by Laureate, a private corporation, on zero-hour flat rates, to supervise PhDs who get a degree from the University of Liverpool. So this is a reserve army who are not protected by the same labor legislation as their university hire colleagues, and are not unionized under the same trade unions. They’re invisible, working from their bedrooms, already since before the pandemic. They are not encouraged or supported to do research and publish, but they do the research-led teaching for research-intensive universities. The worst off were the students, again; students weren’t in the same position within the UK as in South Africa. Students at top universities are very much aware, or made aware, that the value of their degrees is not just the certificate or their employability skills, but the contact made with faculty and classmates and the added value of a network and community. Yet to enjoy that privilege in face-to-face degrees, they are increasingly indebted and pushed into what David Graeber called bullshit jobs to pay their debt off.

But what’s worse – and I know you have been waiting to understand what the hell this is – this is a burnt auditorium in South Africa, at the University of Johannesburg. When I went there for two fieldwork trips, students were in their “Rhodes Must Fall” stage of contestation, which was not just against fees. It was especially for black and colored students to feel citizens at the university where they never felt they belonged. Some of these buildings were burned at a time when students who are on the national funding scheme NSFAS had not received their scholarship because it was outsourced to a private company. They had not received their scholarship for months and they were sleeping rough and they were hungry or they had gone back to their villages; and they were angry. This is the type of students that these digitalized degrees are trying to target. So, just as an aside, and I’ll come back to my main point – we were seeing with my colleagues that this Rhodes Must Fall protest cycle was really bringing back into the university this kind of political society. They are our students and our colleagues, and we can’t pretend that these things don’t affect us as well. I think this is a really opportune moment for anthropology, for academia, to finally get a handle on its privilege and understand that we’re fighting a war. This is a class war, and this is a war that we have to fight together; we’re not in a golden cage that is just based on merit, where we can proceed into an academic career without having to not just face this reality but live it with our own skin.

Just two more remarks. In the meantime, the pandemic happened. Since the the mid-2010s I have been part of a few collectives in Bulgaria or transnationally. Matan Kaminer spoke earlier [at the conference workshops] about LeftEast. But during the pandemic we also established another interesting network, called Essential Autonomous Struggles Transnational or E.A.S.T. This was our attempt, as collectives based in Eastern Europe or working with migrants from Eastern Europe and beyond, to actually collect our knowledge because many of us had started doing, not just activist research ‘on people’ but rather working with people from marginalized groups, with many of whom we shared the same predicaments. So this was also gradually a safe space for all of us to meet and discuss ruptures that dismantled the social fabric of our societies and our communities ever more, and that continually threaten our activism in the guise of conflicts and scandals between us.

These are baby steps that we’ve been taking; but it feels like a lot of these smaller initiatives have gradually started speaking, mostly to ourselves and among ourselves, and then to the West, and then to whoever there is beyond the region. What’s more, and this was part of the 1st of July mobilization that we initiated as a network, this is the Chilean part of it, where they say tocan a una, tocan a todas: fuera Erdogan, fuera Piñera. So, if they hurt one, they hurt everyone, down with Erdogan, down with Pinera. There’s an interesting moment where the connection between Eastern Europe, Turkey, the “East” and Latin America was made. It was strong and for me it was a kind of homecoming, bringing some of this context that I have been studying and working with this one image.

But then there’s Anthropology. And so, as Marie Hermanova [chair of the session] said earlier, I did become the President of EASA. To my surprise, I was voted in with the most votes; that’s how you become the President. I should not have been surprised, as 49 percent of our anthropologists are precarious and I was one of the people running on the anti-precarity platform PrecAnthro. But I think – and initially this talk was announced as a presidential address – the way that I can see a learned society as EASA active is that – especially within anthropology – we now really need to use this power structure, that is marginal but still has some gravity, to expose power structures and oppression at home in our institutions, at the university, in academia – and not just abroad. To put an end to the invisibility and silence of individual suffering; to fight for our rights as collectives of workers sharing vulnerabilities and strengths. I think it is high time that learned societies take an active political stance, not just as a possibility but as a demand and necessity from our disciplines. That is something that the Applied Anthropology Network has taken up seriously this year, and we are all here to celebrate their effort.