“…Here being my Italy –

Where memories spring like geysers,

Crying at me where I place my feet;

Italy which receives me with benignity

This shipwreck – my sick body,

And this feeble candle-light – my soul…”

Emanuel Carnevali, Furnished Rooms, The Return.[i]

1913-2013: One century of temporary Italian migration to the United States. In late April 1913, my great grandfather, Attilio Piana, arrived at Ellis Island, in the New York City harbor, from the French port of Le Havre. At the beginning of November 2013, I also arrived in NYC through JFK airport for a few months of research at one of the universities in the city. Both Attilio and I were the same age, 32 years old. This is a brief intimate and parallel history of our respective migrations. I borrow the expression “intimate history” from the work of Alisse Waterston, who coined the expression “intimate ethnography” in the book where she explores, as an anthropologist and a daughter, the life of her father throughout the 20th century and her relationship with him.[ii]

I knew very little about my great grandfather Attilio before reaching NYC. I was more familiar with the global migration that the Sicilian part of my family had experienced since the beginning of the 20th century. During my first few days in NYC, I looked at the Ellis Island website and found his name. The website of the National Park Service, which now manages the sites of Ellis Island, reports that between 1892 and 1954 nearly 12 million immigrants passed through the island.[iii] Attilio was one of them. A few days after my online research, I decided to go and see what was left of the buildings where Attilio was hosted one century earlier. At that point, I was already familiar with the architecture of Ellis Island. Many movies, among them Nuovomondo (Golden Door) by Emanuele Crialese, include images of the famous Registry Room (also called the big hall for its dimension) and many rooms through which immigrants passed.[iv]

When Attilio arrived in the United States, he was 32 years old, married, and the father of two young children.

One of them was my grandfather, who had been born less than two years earlier. Two other newborn babies had died due to malnutrition. The registry for the boat on which Attilio travelled is easily accessible through the website of Ellis Island. Attilio is number 0030 in the document. His final destination in the United States was the city of Winsted in Connecticut. He paid for his travel himself with the aim of joining his brother. The same boat registry confirms that Attilio was neither a polygamist nor an anarchist. Such a relief to read! More importantly, he was in good physical and mental health. First and foremost this meant that he was able to work and would not be in need of social help. Indeed, his height and weight indicate that he was a tall and broad-shouldered man. He had fair skin, blond hair, and blue eyes.[v]

Attilio’s trip to the United States likely started at the beginning of April 1913. He made his way from the small house where he used to live with his family in the village of Sant’Urbano, in the northeast of Italy. The house where he used to live still exists, although the property ceased to be owned by my family some years ago. My father and his many brothers and sisters were born and raised in that house, before a newer and more modern one was built close by. The place has changed dramatically from my childhood memories, when it was used as a depository for various objects from a past epoch. The floor was made of soil, there was a big fireplace, and a narrow staircase led to a couple of rooms on the first floor. The windows of the old house were small, in order to keep in the warmth. They opened onto a hilly landscape, with land to cultivate below. Behind the house there is a hill where chestnuts, apple trees, wild roots, berries, and mushrooms provided food for the family.

When Attilio left, the region of Veneto was extremely poor. It was only at the end of WWII that many industries were established and set the basis for what would become one of Italy’s richest areas. Attilio was a peasant and most likely illiterate. He was looking for ways to support his family.

Attilio’s migration to the United States was probably not meant to be permanent. He was one of the many seasonal workers who planned to save money and then go back to their countries of origin.

He travelled with other Italians in the boat, some of them from the same region and others from different regions. Attilio might have had a concrete sense of the newborn Italian state while travelling on the boat to the United States. From the 1890s to the 1920s nearly four million Italians migrated to the United States.[vi]

I can only image the fears and hopes, the preparation, and the steps that brought Attilio from his house to the train station in Vicenza. From there he crossed the north of Italy towards the northern regions of France, where Le Havre is situated. While Attilio may have already seen a train before his transatlantic trip, he most certainly had never seen the sea or a boat. He might have heard stories about them, as well as of foreign countries, languages, and habits.

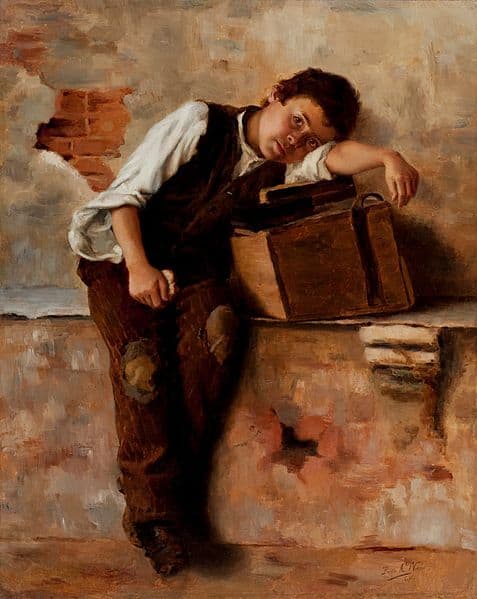

There is much as a historian that I am left to imagine about Attilio’s trip and life. This is because the only evidence about him that I possess is his portrait; the data of his passage in the Ellis Island registry; the dates of birth, marriage, and death that are kept in the church registry of Attilio’s village; some vague and fragmented family memories; and an old yet restored table around which many of my family’s activities took place and on which I enjoy working when I go back to my parents’ place. The lack of evidence is also connected to Attilio’s path. He stayed in the United States for less time than expected. One year after he moved, Attilio returned to Italy and soon passed away. Family legend says that he may have died of a broken heart. The story of my great grandfather does not correspond to the “typical” narrative of the American dream.

One week before going to Ellis Island, I myself had gone through immigration control in one of the hangars of JFK airport. Like my great grandfather, I was also 32 years old. I was not married though, nor did I have any children or anyone else to support back home. There was just me, with my hopes, expectations, and fears. Contrary to him, I am highly educated and could speak English. However, when I stood in the Registry Room in Ellis Island, where migrants used to be interrogated by migration officers, I could not help comparing it to the big hangar of JFK airport. Did Attilio also feel as small and fragile in front of the immigration officer as I did? This is difficult to tell.

Travelling within Europe with a European passport, I never experienced the weight of the state or the restrictions of borders. Waiting for my turn in line in the hangar of JFK, I felt the tension of having to face the immigration officer, even knowing that all of my documents were in order. I felt the fear of thinking that access to this new chapter of my life would depend on someone else making decisions on my behalf.

I felt shame for feeling all of the above, for my lack of courage and self-reflection on the many privileges that I had never questioned before. I thought of the man whom I had met a few weeks before at the American consulate in Milan. While my visa request was approved, his was denied. It is not easy to be a young, colored, and bearded man from Morocco and travel to the US nowadays.

In the hangar of JFK, I hid my tension behind a smile and my credentials. A few days later, in the Registry Room of Ellis Island, there was nobody to smile at, just an empty space filled with large American flags. I cried. That was one of the many moments when I felt the extent to which history is more than the professional empiricism required by the modern standards of scholarly work. There was and there is another truth and other truths, one that no document or archive can recollect, especially when they do not exist anymore. On my visit to Ellis Island, there was a truth that passed through my veins and body before reaching the intellect.

Since then, I have carried out some research on my great grandfather. I contacted the local city hall in Winsted to see whether there were any documents left. Unfortunately, I was not successful. I tried to connect with descendants of Italians in Winsted but their families migrated later than my great grandfather.[vii] My own father conducted some research in the church archives back in Sant’Urbano. For my family and I, the past seemed much closer all of a sudden. Questions of memory, wounds, trauma, and survival were once again brought to light. We empathized with the suffering of Attilio, who was separated from his family and could not cope with those tremendous changes. I thought of those who stayed behind, his wife who became a widower at a very young age and the two children who were raised without a father.

I cannot help but think that this part of my family has endured the experience of migration, physical and psychological privation, warfare, and the epigenetic silent consequences of violence. But I also know that, despite everything, there have been marriages, births, laughs, life, and much lively discussions. In one of the last interviews of Tony Judt for the book Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, he said “the historian’s first responsibility is to get it right – to find out what happened in the past, think of some way to convey it which is both effective and true, and do it.”[viii]

Questioning the history of my own family has brought together the methodological tools of my profession with the fact of facing the silent wounds that passed on from one generation to another.

A hundred years are what separate and bring together my great grandfather and I. Many things have changed and many others have not. Italians are no longer the poorest and least skilled migrants to strive for a better life. Global migration now has different geographies that push desperate people to embark on unsafe boats across the Mediterranean Sea. They risk everything and sometimes they lose it all. These voyages are on the front pages of newspapers on a daily basis. Governments, international organizations, and NGOs constantly struggle with the limits of national sovereignty and the imperative of helping migrants in need.

For how much my life is different from that of my great grandfather, I also did not have much choice about leaving my family and the hills and mountains of my childhood behind. Of course, there is Skype and many other ways to be in touch with those who count in your life. Surely it would be unfair not to frame my migration within a sense of curiosity and knowledge that has been a driving force in my life. However, my own experience belongs to a much larger phenomenon. The 47th report of the Censis, released in 2013, says that the number of Italians going abroad is constantly increasing. In addition to the largely discussed phenomenon of the so-called cervelli in fuga (running brains), there are several other reasons behind it ranging from the interesting opportunities offered by an interconnected world to the frustration and disenchantment with a country where there are very few jobs.[ix]

While there is something disheartening about being a historian and working on topics connected to migration, I also believe that, as a profession, we run into stories that we have the responsibility to understand and share, even when this entails opening up the history of our own families. In times of uncertainty, increasing xenophobia, racism, warfare, outbreaks, and protracted humanitarian emergencies, writing and sharing history is more than ever a political commitment.

My gratitude goes to my father, Attilio Piana, who conducted research in the church archives of Sant’Urbano and who mobilized our family in a spontaneous project of memory recollection. Thanks to the T-riders and my fellow colleagues at the Telluride Association Michigan Branch for engaging with my professional and personal query. Things that maturate for long months can take only a few hours to be written.

Notes

[i] Emanuel Carnevali and Dennis Barone, Furnished Rooms (New York, NY: Bordighera Press, 2006), 70.

[ii] Alisse Waterston, My Father’s Wars: Migration, Memory, and the Violence of a Century (New York: Routledge, 2014). See the prologue. Thanks to Riccardo Bocco for suggesting it.

[iii] See http://www.nps.gov/elis/index.htm (last seen May 2, 2015). Since the early 1970s, an oral history project has been going on with the scope of recording the memories of those who arrived and were checked at Ellis Island, as well as immigration officers, military and medical staff. See http://www.libertyellisfoundati on.org/oral-histories (last seen May 2, 2015). See also the documentary “Island of Hope. Islands of Hopes.”

[iv] Much has been written on the Italian emigration to the United States. For some references see Francesco Durante, Italoamericana: Storia e Letteratura degli Italiani Negli Stati Uniti (Milano: Mondadori, 2001).Emilio Franzina, Gli Italiani Al Nuovo Mondo: L’emigrazione Italiana in America 1492-1942 (Milano: A. Mondadori, 1995). More generally, Piero Bevilacqua, Andreina De Clementi, and Emilio Franzina, Storia Dell’emigrazione Italiana (Roma: Donzelli, 2001).

[v] Registry of Ellis Island, States immigration officer at the port of arrival. Must upon arrival delivers lists thereof to the immigration officer. This (white) sheet is for the listing of STEERAGE PASSENGERS ONLY. Arriving at the port of New York, April 19, 1913.

[vi] Roger Daniels, Coming to America: History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1990). See the good book by Sabina Donati, A Political History of National Citizenship and Identity in Italy, 1861–1950 (Stanford University Press, 2013), in particular chapter 4 “O Migranti o Briganti:Italian Emigration and Nationality Policies in the Peninsula,” which tackles the changing attitude of the Italian liberal state towards first and second generation immigrants.

[vii] See the Cornelio Legacy Film, https://winsted1948.wordpress.com/ (last seen May 2, 2015).

[viii] “Postwar: an Interview with Tony Judt,” by Donald A. Yerxa, in Historically Speaking, The Bulletin of the Historical Society, Volume II, Number 3, January-February 2006.

[ix] Rapporto Censis, La società italiana al 2013.