That humanitarian language, materials, and practice offer a space for politics to hide (Feldman, 2018, p. 131) can probably not be more clearly illustrated than through the fact that the UN Security Council, as genocide unfolds in Gaza, calls – not for a ceasefire – but for a ‘humanitarian pause’ (United Nations, 2023). It is in this humanitarian space that various actors, not least Palestinians themselves, have done and still do, politics. But that not even a so-called ‘humanitarian pause’ can be realised in this very moment raises questions not only of the limits of politics interweaved in humanitarian language, materials, and practice, but also of the research that we as anthropologists of humanitarianism conduct within that same space. It is Israel’s brutal war on Palestinians, alongside its unconditional support by the West, that urges us to talk about these limits.

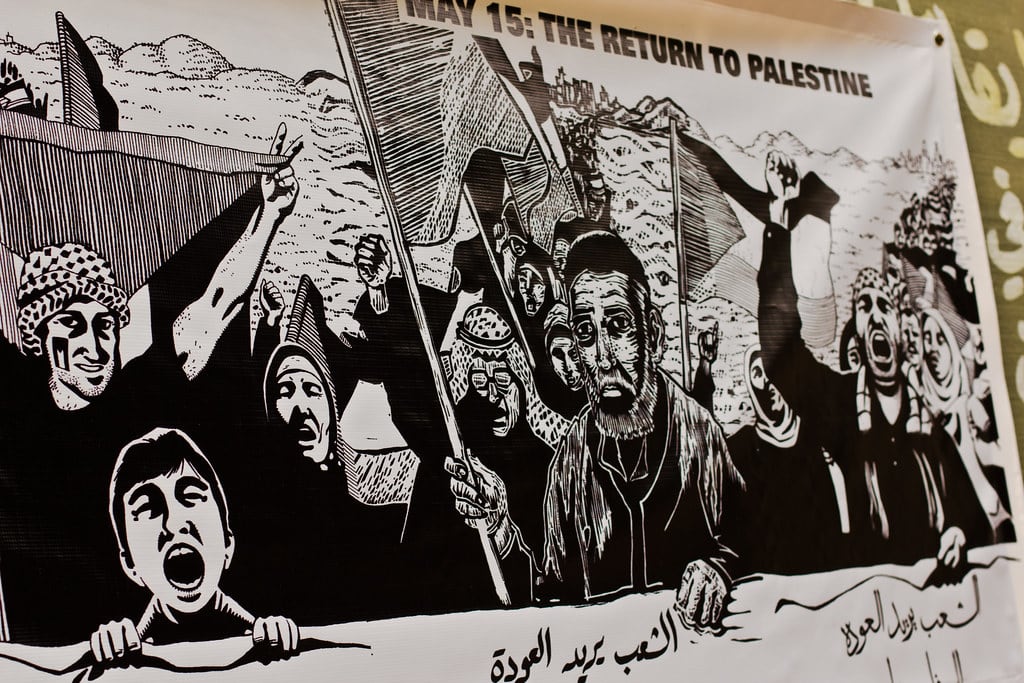

Doing research on humanitarianism, its interventions and everyday practice, I work closely with Syrian refugees and local humanitarians in Jordan. In my PhD, I explore how bureaucratic procedures help to (re)shape and sustain a humanitarian aftermath – the transformation of humanitarian organisations’ emergency interventions into other forms of engagements, stretching far beyond their initial aims (McKay, 2012). Since the Nakba in 1948, following the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967, Palestinians have fled to Jordan in many moments of occupational violence, shaping a demographic, social, and political reality that is ever-felt in Jordan (Massad, 2001). Many of my interlocutors, humanitarians working with Syrian refugees, were Palestinians. While their own experiences of dispossession and displacement often shaped their reflections on the provision of humanitarian assistance to Syrian refugees, these experiences also often informed Syrian refugees’ reflections on displacement, past events, present conditions, and future possibilities. All these experiences unfolded within the humanitarian space that Ilana Feldman discusses; a space that – at best – allows for addressing problems of the here and now, but seldom offers fundamental changes for later and elsewhere. If it is ever a space for politics, it is for a politics of a specific, non-threatening sort. And it is precisely what Feldman points to when she analyses ‘refugee politics.’ Humanitarianism offers a space that allows Palestinians to make claims as refugees – never as Palestinians. As the failed UN resolution on a ‘humanitarian pause’ suggests, it is also a space where humanitarian actors can make subtle political claims.

But what the current siege and bombardment of the occupied Gaza strip make visible – for anthropologists like myself, who work in the region and who have fostered close and lasting relationships with people who are directly or indirectly affected by the ongoing events – is the fact that, like refugees and humanitarians, anthropologists cannot obscure their politics. Doing ethnography involves deep social engagements for months in the same place, with the same people. Many of our encounters and acquaintances then transform into other forms of lasting social relations and friendships. As we leave the physical spaces of our fields, we are mutually invested in sustaining many of these relationships as they have become significant in our personal lives, extending far beyond our research, which only enabled our initial encounters. With Israel’s brutal violence on the people in Gaza, such engagements demand from us to expose our politics.

In the accelerating Islamophobic political context in Europe, which during these last weeks has proved to play such a fundamental role in the direct danger of occupation, it is imperative that no one remains silent. For those of us who are personally and emotionally engaged with people directly or indirectly living the brutal atrocities in Gaza, it is not only a political and moral position as concerned citizens or as researchers, but also a personal, emotionally-charged obligation. Checking up on friends and acquaintances, sharing devastating news with each other on different social media platforms, discussing the current political climate in the world – from protests in Jordan or elsewhere, to the problems of media portrayals in the West and beyond – are meaningful forms of solidarity. While there is no room for uncritical, equivalencing statements like “taking both sides” in these engagements, neither is there in our professional responsibilities as researchers. For, there is a particular anthropological demand that lurks in this growing routinisation of the idea of some people dying – what Ghassan Hage (2020; UNAM-Históricas, 2016) calls ‘cultures of exterminability’.

[T]his demand urges us to take a political stance for which there is evidently no room in the humanitarian space.

In this moment, most western states and institutions not only close their eyes, but unreservedly support the atrocities carried out by the Israeli state in the name of “self-defence” and, simultaneously, wholeheartedly neglect Palestine’s own right to the same. As such, this demand urges us to take a political stance for which there is evidently no room in the humanitarian space. This demand is what conditions the very ethical right (not the noun but rather the adjective ‘right’ as opposed to ‘wrong’) of anthropologists like myself to academically engage with Arab, Muslim, and in this very case, Palestinian communities. I do not mean that we have to agree with the political orientations of our interlocutors, but rather that we need to unconditionally oppose oppression, occupation, and extermination. Making this claim is to say that, in the increasingly polarised political discourse, where Western states’ repeatedly and more intensely engage in a dangerous public de-sensitisation to the death of Palestinians (which also extends to Arabs regardless of nationality and religion), we cannot hide our politics packed in a language of ‘humanitarian critique’. It is not enough. And it is not enough precisely because such subtle political engagement contributes to the temporal break of ‘past destruction’ and ‘present displacement’ and does therefore not really address, but only acknowledges, what has caused present conditions.

Beyond exposing our own politics, it is our responsibility as anthropologists of humanitarianism to ring the alarm when humanitarian language ceases to even accommodate the word “ceasefire.”

But to say that that is not enough implies revisiting the role of anthropologists working on humanitarianism. In my view, our role is not only about asking what the humanitarian space (dis)allows actors to do, but about critically challenging the limits of the space itself. More importantly now that we stand on the brink of genocide, we have a duty to expose the danger when this already limited space disappears. Beyond exposing our own politics, it is our responsibility as anthropologists of humanitarianism to ring the alarm when humanitarian language ceases to even accommodate the word “ceasefire.” We need to ask the question: How has calling for a ceasefire become so political that whoever uses the word is accused of antisemitism? What is next? Claiming that Palestinians are humans? Some would certainly say that we are already there. That Muslims are humans? Or Arabs in general? I am pointing here at the danger of creating a culture that makes a people exterminable (Hage, 2020; UNAM-Históricas, 2016). What if we reach a place when even calling for a ‘humanitarian pause’ becomes too political? Posing this question is a way to refuse this shrinking humanitarian space in which the word “ceasefire” must be interwoven in subtle politics. It is not only our role to highlight, but also to refuse such development. The people in Gaza do not need a humanitarian pause – they need a ceasefire. They need the genocide to end. An end to the occupation. And if it has become too political even for the UN Security Council to utter those words, then at least we, as anthropologists working in the same humanitarian space, should.

Bibliography:

Feldman, I. (2018). Life Lived in Relief: Humanitarian Predicaments and Palestinian Refugee Politics. University of California Press.

Hage, G. (2020). Antiracist Writing. In C. McGranahan (Ed.), Writing Anthropology: Essays on Craft and Commitment. Duke University Press. https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/2730/chapter/2052305/Antiracist-Writing

Massad, J. A. (2001). Colonial effects: The making of national identity in Jordan. Columbia University Press.

McKay, R. (2012). AFTERLIVES: Humanitarian Histories and Critical Subjects in Mozambique. Cultural Anthropology, 27(2), 286–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2012.01144.x

UNAM-Históricas (Director). (2016, September 30). Cultures of exterminability, con Ghassan Hage. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JWfQYBhHqo

United Nations. (2023, October 18). Israel-Gaza crisis: US vetoes Security Council resolution | UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/10/1142507