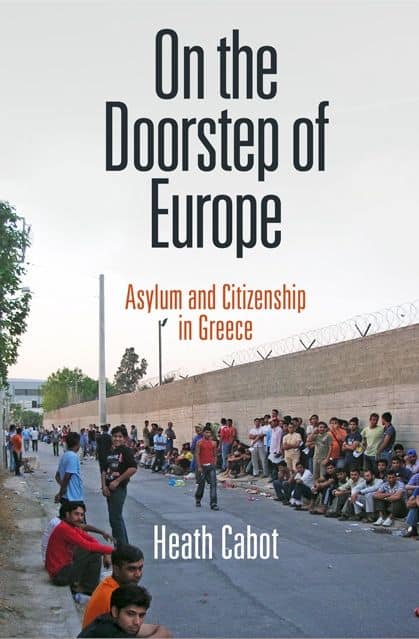

Heath Cabot’s first monograph, entitled « On the Doorstep of Europe: Asylum and Citizenship in Greece », will come out with the University of Pennsylvania Press, in its series The Ethnography of Political Violence, in June 2014. The book is an ethnographic exploration of the regime of political asylum in Greece that unpacks the dilemmas posed by both human rights law and European governance. Allegra had the privilege to ‘sit down’ with her for a (virtual) discussion on her book and on the European asylum crisis.

Allegra: Your book is based on long term fieldwork in the legal department of an Athens based NGO (which you call Athens Refugee Service) in charge of processing asylum claims. Why did you decide to study ‘asylum’ from the perspective of bureaucracy? And why from Athens?

Heath: My interest in and emphasis on bureaucracy did not precede the project. The NGO site was, in many ways, a site of convenience, as I believe many of our fieldsites are. The NGO – which manages thousands of clients — provided an entry-point into a complex nexus of phenomena that, to me, constituted asylum as a process. Lawyers, asylum seekers, interpreters, social workers, police, bureaucratic forms (both as aesthetic forms and, literally, documents), and intense intellectual, ethical, and emotional engagements – all emerged at this site. I was also able to track these persons and things outward from this small office into the wider city, the wider country (to the borders), and even elsewhere in Europe (IE, the European Parliament and other countries where persons travelled after coming to Greece, primarily Italy). The book, however, focuses largely on the office and the work in Athens, since it was just so rich, but I try to show that the office is entangled in so much more.

Heath: My interest in and emphasis on bureaucracy did not precede the project. The NGO site was, in many ways, a site of convenience, as I believe many of our fieldsites are. The NGO – which manages thousands of clients — provided an entry-point into a complex nexus of phenomena that, to me, constituted asylum as a process. Lawyers, asylum seekers, interpreters, social workers, police, bureaucratic forms (both as aesthetic forms and, literally, documents), and intense intellectual, ethical, and emotional engagements – all emerged at this site. I was also able to track these persons and things outward from this small office into the wider city, the wider country (to the borders), and even elsewhere in Europe (IE, the European Parliament and other countries where persons travelled after coming to Greece, primarily Italy). The book, however, focuses largely on the office and the work in Athens, since it was just so rich, but I try to show that the office is entangled in so much more.

Athens is, quite simply, the bureaucratic center of the asylum process, so it made sense to locate the study in Athens. But an unintended aspect of the book was that it also became an exploration of the dramas that are transforming the city itself. As I inhabited and moved through this city, through the networks that I encountered there, I began to trace the urban transformations taking place through immigration and also asylum, as Greece has had to come face to face with (if not accept) its own diverse histories and the presence of new “others” who now claim lives and entitlements there (though often without success or only partial success). Ultimately, the book is about citizenship: about who gets to inhabit the polis (literally, the Athenian polis, but also a city of the imagination, myth, and of speech – which I frame as I site of recognition – formal and informal — of persons in a polity).

Allegra: The book is built around the notion of ‘tragedy’, and it is even composed of 3 acts, like in a classic Greek drama. The emblematic image that comes to mind when one thinks of the tragedy of asylum in Europe is one of a boat full of migrants sinking on the shores of Lampedusa. But the picture that comes out of your book is somewhat more complex as you suggest that tragedy also includes a transformational dimension. Can you tell us a bit more about the significance of this metaphor for your argument?

Heath: One has to be very careful with employing tragedy in exploring migration and asylum, because it is very easy for it to become a caricature: as anthropologists and perhaps advocates, we can very easily reproduce the very images and narratives that certain publics – and bureaucratic audiences – want to be “tragic,” in a more simplistic sense. For instance, the “standard” refugee story, which speaks of displacement and violence, as well as those very real images of sea-death and unspeakable loss (in Lampedusa and in the Aegean) are often discussed as “tragedy,” in a way that does not do justice to their unspeakability. Moreover, as I and others show, such narratives themselves can cause profound violence and exclusion, demanding that persons present themselves as vulnerable victims in particular ways in order to gain protection. But tragedy, as a dramatic form, is much richer and more complex than that, and I think it is worth recuperating (just see Judith Butler’s recent book with Athina Athanasiou). It is about an active emotional encounter with one who is simultaneously self and other. The heroes of tragic drama were themselves often in exile, often seeking refuge, and they ultimately emerged as both the human heart of the polis and the city’s cast-aways. And don’t forget, the sovereign itself was often unjust (IE, Creon in Antigone), but the hero heralded a kind of city that could – perhaps only in death — transcend the sovereign. Through the encounter with the drama, the active is able to see him or herself in a kind of mimesis that catalyzes a release of a spirit of excess and emotion, as well as the capacity to see the world (and the self and the city) in a new way.

Heath: One has to be very careful with employing tragedy in exploring migration and asylum, because it is very easy for it to become a caricature: as anthropologists and perhaps advocates, we can very easily reproduce the very images and narratives that certain publics – and bureaucratic audiences – want to be “tragic,” in a more simplistic sense. For instance, the “standard” refugee story, which speaks of displacement and violence, as well as those very real images of sea-death and unspeakable loss (in Lampedusa and in the Aegean) are often discussed as “tragedy,” in a way that does not do justice to their unspeakability. Moreover, as I and others show, such narratives themselves can cause profound violence and exclusion, demanding that persons present themselves as vulnerable victims in particular ways in order to gain protection. But tragedy, as a dramatic form, is much richer and more complex than that, and I think it is worth recuperating (just see Judith Butler’s recent book with Athina Athanasiou). It is about an active emotional encounter with one who is simultaneously self and other. The heroes of tragic drama were themselves often in exile, often seeking refuge, and they ultimately emerged as both the human heart of the polis and the city’s cast-aways. And don’t forget, the sovereign itself was often unjust (IE, Creon in Antigone), but the hero heralded a kind of city that could – perhaps only in death — transcend the sovereign. Through the encounter with the drama, the active is able to see him or herself in a kind of mimesis that catalyzes a release of a spirit of excess and emotion, as well as the capacity to see the world (and the self and the city) in a new way.

In contemporary Greece, tragic drama is often a source of humor (just see the classic film Never on Sunday), of joking but penetrative commentary, and it also haunts the archaeological landscape. I settled on the image of the Eumenides as a kind of backdrop to the book because it provided a way to think of justice outside the formal framework of judgment, as well as the transformative effects of events that happen at the margins of formal law. The book is about just that. In writing, I also became more and more interested in the overlaps between the similar aesthetics that characterize the law, ethnographic writing and knowledge, and tragic drama (in the more complex sense). The case, the interview, and other forms endemic to both asylum seeking and ethnography all contain aspects of “social drama” (see Llewellyn and Hoebel, Gluckman, and Turner). What I found in my examination of encounters between asylum seekers and NGO workers is that transformation (of opinions, of norms, of advocacy strategies, and of ethics) were overwhelming aspects of the experiences of aid workers and in many cases asylum seekers as well. These transformations, however, were NOT always redemptive. But there was a dialogical aspect to them, even in their moments of violence. Finally, an emphasis on the tragic – an overwhelming sense of the impossibility for ameliorative action on the part of aid workers — provided a way for me to characterize the humanitarian ethics at work at the NGO.

Allegra: Limbo is at the heart of the asylum regime, not only for the asylum seekers whose future lives very much depend on the decisions taken by civil servants, but also for the bureaucrats caught in the complexities of European governance. For instance, you qualify the bureaucratic procedures constitutive of the asylum regime as mythopoesis or ‘myth-making’. How do ‘stories’ become audible (or not) in asylum claims?

Heath: The defining feature of the asylum process, as I have found it, is radical uncertainty for all involved. It entails forms of judgment based on nothing but things like stories and performances. And for claimants and bureaucrats alike, the system is so convoluted and chimerical that traditional forms of knowledge practice (things like evidence, consistency, and credibility) – while formally valorized – are persistently exposed in their failures.

For me, mythopoesis refers to the practices through which asylum seekers, aid workers, and bureaucrats seek to manage radical uncertainty. It refers to the reliance on folk knowledge, rumours, fantasy, deep speculation, the ghostliness that persons take on in the encounter with the law, and other forms of knowledge that haunt the asylum process. Nevertheless, the “story” – the refugee story – must somehow be made to speak or be spoken in a way that the law might recognize. The tension between the required speakability of that story, and the unspeakabilities that mythopoesis underscores, is at the center of these bureaucratic encounters.

I found that more often than not, the mythopoetic aspects of judgment and bureaucracy greatly overwhelmed the more speakable aspects – and that aid workers, clients, and bureaucrats often recognized that openly. The “speakable” – the demands of formal law – was the “as if” that everyone inhabited, but most often with the recognition that it was insufficient.

Allegra: Your book is also about the unexpected ways in which asylum seekers manage to maintain some degree of agency, even in situations where the ‘theatre of the law’ tends to discipline and reduce their capacity to speak. How do these ‘legal encounters’ sometimes create the conditions of possibility for undermining the system from within?

Heath: I think my empirical emphasis on the dialogical aspects of aid encounters provides space for showing how asylum seekers weren’t simply made to “fit” particular typologies of worth and deservingness, but sometimes shaped those typologies, actively and sometimes less actively. Moreover, I tried to take seriously also the refusal of many to speak the stories that they were supposed to speak. Exclusion (and in one particular case, even death) was often the result of such refusals. But the marks they left on those they encountered – a kind of haunting – frequently had lasting effects on the ways in which advocates and decision makers approached future judgments. I also tracked how cases were often built from “below” through the slow accretion of information that asylum seekers actively produced, which shaped and reshaped the kinds of cases that became possible through a kind of (asymmetrical of course) collaboration with advocates.

Allegra: The exclusion of ‘strangers’ – like the ritual exile of the ‘pharmakos’ aimed at purifying the polis after disasters in Ancient Greece – is also a means to redefine terms of belonging and citizenship. With the re-emergence of neo-Nazi groups like Golden Dawn is the danger of an increasingly exclusionary form of citizenship more real?

Heath: Yes, indeed. Very much. It’s terrifying. But I also see SOME possibility here for new forms of citizenship. While I was conducting my primary fieldwork (2006-2008), migrants and asylum seekers were greeted with a kind of toleration – a quiet toleration. But (see Robert Hayden’s work) “tolerance” is often built on forms of invisibility and ongoing exclusion, not real forms of co-presence. What is now happening is that migrants and “foreign” residents (IE, those who cannot lay claim to blood ties with the territory of Greece) are demanding entitlements in the public sphere in new and often radical ways, and anti-racism movements are growing powerfully, alongside these rising forms of explicit and violent racism.

Allegra : What does your study of the regime of asylum in Greece reveal about Europe as a political project more generally ?

Heath: I think my study shows that in Europe (at least in its current configuration), the management of migration and asylum (and perhaps also finance) works only through the ongoing marginalization of those countries on its geopolitical and « moral » borders. Europe is only possibe with the sleight of hand that allows its borders to take the fall for the failures of the whole. Europe « needs » Greece – and to use and abuse it. I hope there are other possibilities for Europe, but from my perspective on Europe’s thresholds, it’s hard to see otherwise.

For more academic insights on Greece:

– Read our interview with Dimitris Dalakoglou on state, violence, infrastructures and public space in Greece here

– Cabot, Heath. 2012. « The Governance of Things: Documenting Limbo in the Greek Asylum Procedure ». PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 35 (1): 11‑29.

———. 2013. « The Social Aesthetics of Eligibility: NGO Aid and Indeterminacy in the Greek Asylum Process ». American Ethnologist 40 (3): 452‑66.

Cowan, Jane K. 1990. Dance and the Body Politic in Northern Greece. Princeton University Press.