Earlier this week, Allegra published a critique of Elizabeth Povinelli’s keynote at the EASA 2014 in Tallinn written by Sylvain Piron. It did not take long for the controversy to flair up in the social media as ‘pro-Povinellians’ flew to the rescue of the academic star, denouncing the unfairness of Piron’s harsh judgement. Some elements of Piron’s arguments were certainly ‘raw’ and lacked subtlety. Yet his post also addressed points that need further dissecting – and it certainly can be acclaimed for triggering discussion.

As the moderators of an academic blog, we feel that one of our primary responsibilities is to facilitate debates. To us this duty becomes particularly grave when the future of our discipline is concerned. This angle concretizes the wider context for Povinelli’s talk – a context that we feel has so far remained largely unarticulated. Subsequently we want to offer some critical reflections of our own.

As the moderators of an academic blog, we feel that one of our primary responsibilities is to facilitate debates. To us this duty becomes particularly grave when the future of our discipline is concerned. This angle concretizes the wider context for Povinelli’s talk – a context that we feel has so far remained largely unarticulated. Subsequently we want to offer some critical reflections of our own.

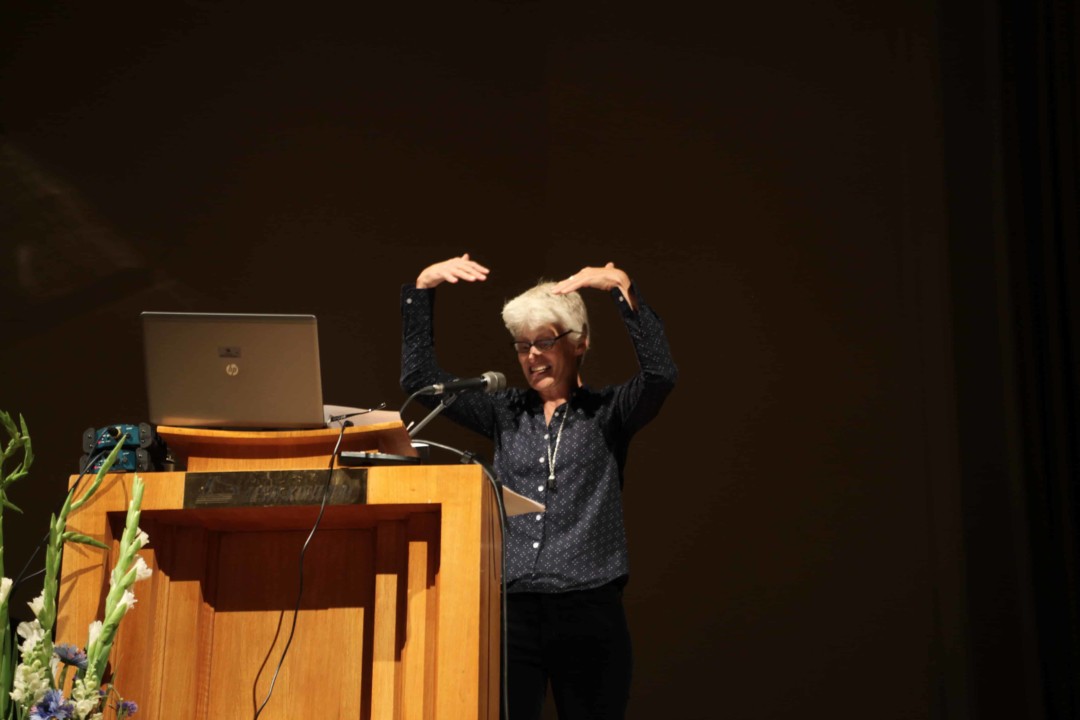

One recurring theme in the critique toward Piron’s analysis has become his focus on Povinelli’s gesturing and body language, with some commentators even suggesting that similar observations would never be written – let alone published – in case of male scholars. Yes, Piron’s observations were detailed, intrusive – certainly intimate, to echo one of the slogan’s for the Tallinn Conference – but we do not want to dismiss of them that easily.

For Povinelli’s persona embodied, or more accurately perhaps, should have embodied, a sense of invigoration, inspiration – the future – of the discipline that we are jointly so passionate about. This was, at least, our reading of the collective mood that characterized this first joint gathering of all the anthropologists who had travelled far and wide – after an interval of two years since the last Conference of the most important professional association of European anthropologists – to eventually find themselves in the magnificent Tallinn Concert Hall.

Expectations ran high – not just toward Povinelli’s speech but for the Conference in general. We all know that times are dark, and let’s not even get started on the absurdity of ongoing university managerial reforms! Perhaps with this Conference we were finally on our way toward collective exhilaration and (renewed?) societal relevance for our arduous professional endeavours.

Against this background Povinelli simply got off on the wrong foot. Even if intended as humorous or ironic, the audience never seemed to forgive her for her opening comment of ‘not really wanting to be there’. And yes, we wonder too: if she didn’t want to come, why did she – or why did she share her hesitation?

Add to this remark issues of European inferiority / American superiority complexes that we briefed at in our preliminary remarks of the talk, and one grasps far better why from thereon her talk sort of fell on a ‘hostile crowd’.

This context explains, perhaps, part of the intensity that her talk awakened. Here we need to be truthful. As much as it pains us to dwell on such collective dismay, we would not be accurate if we did not repeat, again: people really did not like her talk. We could continue here with varying degrees of upset and bodily expression of dissatisfaction that we encountered, but we feel that this message has become sufficiently clear even in their absence.

However, this dislike was ultimately not caused by her body language or symbolic embodiments of ‘hope’, but because of the talk’s content.

What was the fundamental problem? To us, quite bluntly, instead of helping our beloved discipline to break free from a European/North-American legacy that has tended to exoticize the ‘other’ and make him/her become the silent object of the anthropological gaze and Western knowledge consumption, it resonated, even strengthened this troubling legacy.

First there were Povinelli’s persistent reminders of her close intimacy with the natives – the use of the pronoun ‘we’ as if wanting to secure her legitimate position for representing the world of the indigenous groups she studied. “We eat together. We raise kids together. We make films together”. Was she emphasizing that it is extraordinary for an anthropologist to share the everyday activities of her informants?

This question grew more intense as her talk continued, and the ‘other’ made her appearance via her disappearance, sort of. For – even if her projects entertain a more nuanced reality – in her talk the ‘native’s point of view’ never really became a part of the equation.

Instead, we were bombarded by Deleuze’s and Guattari’s abstract notions of intersection and assemblages alongside anthropological buzzwords with virtually no ethnographic grounding. As her talk continued, the geontologies she initially intended to make visible vanished into the ‘black boxes’ of NTIC and mediated communication.

Once again, perhaps because of the ‘wrong foot’ with which things got started, we along with so many of our colleagues left the Concert Hall with a bitter sense of déjà-vu. Further, we found ourselves having nagging doubts toward the EASA Scientific Committee: they could not have invited Povinelli as the keynote speaker precisely because of how her work resonates with colonial superiority complexes…

We all know the following, but in the spirit of doing things properly, let’s go back to the basics. Since Malinowski, the core method of our discipline has been participant observation, a method that (ideally) offers us access to the moral universes and cosmologies of those whom we observe via participating. We are all familiar with conceptualizations of ‘the exotic other’ as well as problems thereof.

Yet, we feel that we need to ask once again: just what is ‘the exotic’ that we study collectively as anthropologists? Something identifiable visibly – marked by colourful ‘tribal’ attire or at minimum, differing racial identifiers – or something less conspicuous and evident, yet simultaneously far more profound? What precisely does ‘the exotic’ mean in our analytical equation? It is to this question that we feel that Povinelli’s choice as a keynote offered a disappointingly familiar, even mundane response.

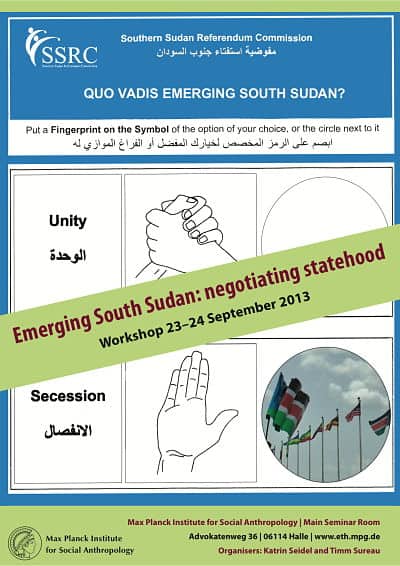

For us this is the fundamental issue at stake that should become also the focal point in regards to Povinelli’s talk and the EASA’s advisory board in inviting her as the keynote speaker. This discussion resonates with the hordes of anthropologists who have concretely moved away from the remote and the exotic, conducting fieldwork instead ‘at home’, in settings where ‘radical difference’ cannot be found but rather ‘radical sameness’ often prevails.

To us, it is as much on the discovery of radical sameness as it is in difference where the truly ‘exotic’ lies.

In addition, globalisation has blurred the divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’, forcing us to think anew the methodological foundations of our discipline and to devise new forms of collaboration. A radical critical anthropology, in our view, implies developing new forms of research collaborations where lateral reason can be stimulated.

As Ghassan Hage argues, anthropology remains ‘a permanent point of first contact’ where it becomes possible to see the ‘weird’ both at our doorstep and further afield.

All of these realizations were, in our view, absent from Povinelli’s account of the Karabing. Despite of the presence of visual ‘exotism’, absent was a sense of the ‘weird’ or new as everything felt familiar. Perhaps unexpectedly, this sentiment was strengthened rather than alleviated by the element of her talk that, undoubtedly, did address something factually new: the technologies that were cardinal in her project.

To us her talk conveyed a notion of collaboration that was marked by an absence of critical engagement with the unintended effects of new technologies in mediating representations of indigenous people’s life world. As one of our colleagues pointed out as we discussed the talk on the same evening:

“Instead of learning from indigenous people how geography and biography are weaved together to produce their unique social imagination, she seemed to blindly trust the new media technologies’ capacity to embed without altering traditional, historical and contemporary knowledge back into the landscape from which it came ».

That indigenous knowledge became a sort of virtual artefact to be displayed in an online museum directly available for consumption did not seem to represent a major ethical problem, since the indigenous people themselves were eager to take part of the experiment. The alteration Povinelli advocated for turned out to apply not to the anthropologist but rather to the already disempowered people she purported to assist in their claims for the recognition of their land.

This brings us back to the main reason of our discomfort we briefly mentioned earlier: namely, the fact that Europe has a long enough history of plunder of other cultures’ material and immaterial heritage to awaken suspicion when similar projects are being reactivated under the disguise of new technologies and post-structuralist justifications.

We want to conclude our discussion – and simultaneously this entire chapter of our EASA 2014 project – by sharing our hesitation in writing this post. Yes, Elizabeth Povinelli’s achievements are vast and her career is so impressive that she likely has the kind of ‘scholarly armour’ to take the critique. This is further likely not the first or worst time that she hears zinging remarks on her work.

But there is still something about the might of the written word, alongside with the immediacy of the online world, which makes us hesitant. There simply is an ‘iffy’ feeling about spilling all this virtual ink over the talk of one single scholar.

What about the perspective of us, the authors of this post? Would we be wiser if we continued to ponder over these views for a bit longer before sharing them in public – certainly it would feel safer to hide behind layers of peer review and the watering-down effect of time.

But are we not addressing here precisely the collective sentiment that contributes to a certain stagnation of our beloved discipline – hence also stripping us of the more general possibility to participate in ongoing societal discussions happening right now?

Is it thus not better that we take a leap of faith and risk something (our reputation?) by actually saying something? Yes, gossip and innuendo have always been inseparable elements of scholarly work, as a wise mentor reminded us as we balanced the best course of action in the case at hand. Would it be better if all of the above was left as just that, or is the possibility to share them with our scholarly community to the benefit of us all?

We know not for certain, but we are persuaded of this: it is both urgent and rewarding to keep addressing these questions & navigating this border to the unknown.

It is in this spirit that we conclude our coverage of this chapter of EASA 2014 and warmly invite you all to join us next week as we celebrate Allie turning 1!

I would like to add to this discussion from outside Europe and the USA. I was not at the keynote in question, but as an Australian I am familiar with some of the conditions that gave rise to the criticisms of Povinelli’s presentation.

I suggest that the response of discomfort to the presentation in part stems from the facts of neo-colonial conditions in Australia that shape interpersonal relationships as well as collaborative projects. This film work was presented at the AAS conference in Canberra last year with the Aboriginal collaborators present and I was reminded of earlier occasions when remote, black, community artists or performers accompany their white anthropologist to the city and are displayed along with their work, to an urban audience. Such occasions commonly evoke some uneasiness that echoes elements of these criticisms.

Vocal, educated and assertive Aboriginal individuals have their voices — and their disputes — heard in Australia, but anthropologists often work with groups who are silenced because they are without mainstream cultural capital. How, or whether, their voices can be brought into the public arena is a difficult and politically fraught question as we know. The anthropologist or linguist can easily appear like the puppet master when she ushers people with different manners into the public domain and invites them to speak.

More commonly, the researcher finds a vocal Aboriginal collaborator with a convenient post-colonial vocabulary to front a collaborative project, or to avoid the visibility of now anthropologically unfashionable ‘difference’, which is often aligned with blackness.

For anthropologists working in settler colonial states there is ‘no space of innocence’, as both indigenous peoples and anthropologists find themselves entangled in all-encompassing public and political processes fraught with complex and ambiguous loyalties and priorities.

I want to add that Beth Povinelli has said that the fundamental focus of her work is the analysis of contemporary liberalism, and it is as a fresh and incisive critic of the liberal governance of Indigenous Australians that her work was eagerly taken up — or rejected — by anthropologists who live and work in Australia.

Thanks for this post. There are plenty of interesting issues to chew over here. I wasn’t at the talk, and don’t want to comment on your treatment of that or its content. I was however struck by your discussion of this thing you like to refer to as “our beloved discipline,” and the suggestion that in some enlightened future there should ideally exist an anthropology that transcends ongoing regional and sub-disciplinary methodological differences. Do you really think that would be a good thing? As an antipodean I was also struck by your focus in this aspect on the European/North American legacy, and wonder where the so-called “global south” (I hate that term) and more specifically real south (eg. of Povinelli’s research and talk and as discussed in the comment above) fits into that divided unit? Perhaps its hiding under the “/” that connects/separates those two entities, or is completely slashed out by it/them? I’m also a bit confused by your comment about peer review. I’m sure you are being very brave indeed in posting this blog entry, but to suggest that the peer review processes is about creating barriers to a somehow more authentic form of immediacy and truth misses the point. Even so, your argument concerning the potential importance of getting initial reactions and opinions out there into the public domain quickly I tend to agree with. I’m pretty sure Elizabeth Povinelli would too.

I just read the post above because Rex over at Savage Minds linked to it in his most recent post. Writing from the US, I am struck by the following sentence: “In addition, globalisation has blurred the divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’, forcing us to think anew the methodological foundations of our discipline and to devise new forms of collaboration.” Current events in Ferguson, Missouri make clear that some ‘us’ and ‘them’ divides have most certainly not been bridged by globalization–certainly not racial divides between Black and White, especially in the US but not only in the US (i.e. this divide also exists in Europe, even if does not take the same exact forms in Europe. As such, I feel troubled by the kind of uncritical claims about globalization being made upon the ability of Elizabeth Povinelli’s White body’s ability to be summoned to speak at the Tallinn conference. I think the problematic claim made above about globalization blurring ‘us’/’them’ divides is predicated upon assumption of a normative White subject which needs to be acknowledged, not taken for granted. Please address.

Any collaboration between anthropologist and “others” is going to be critiqued in this way. She is going to be translating for her peers – there is no way around it. Likewise, if the “natives” take the anthropologist along to some meeting of theirs, there will be the opposite situation. I am not sure what these Euro-critics propose instead. Also, it seems to me that if the Australian aborigines were complaining, but interestingly it is other Euro-anthropologists who seem to be the righteous ones here….

She gave a public lecture at Victoria U. Wellington NZ. I found it totally incomprehensible. It was a monologue in a pretentious rambling style delivered with the air of someone pretending to give a scholarly talk. People walked out in the middle, something unusual in a very civil place.

Just saw Povinelli’s her lecture in Finland, Orivesi, Nordic Summer School – it all had to do with geontopower – a concept she never managed to define, never managed to argue for through any example, instead providing only an incoherent nonsensical ramble about “late liberalism” and the way it relates to geontopower, something that can be boiled down to the life – non-life dichotomy (omg some things have carbon and some don’t – scandal!). She suggested that in this sense the Aboriginal population is being perceived by the people in power as non-life, i.e. as rocks (duh – have there not been many more interesting and fitting social critiques of exactly this power relation before – and I am sorry, even the oppressor can see that these people have an agency…rocks, really, is it not precisely their acts, behavior, modes of enjoyment that, among other things, has been bugging the state?). No single example of this power at play in real social, political or economic encounters. It boiled all down to random name-dropping, some assemblages, and in the end she even got Kant and the sublime completely wrong. An utter disaster. The presentation style can be summed up as: “you have all read Foucault, so I do not have to explain this to you”, and so on – yes, we have read it, but it would be nice to see what exactly in Foucault is being critiqued or remedied by the concept, but alas, forget an answer amidst this verbal vomit. And in between – a little bit of stand up comedy – you know the moments where the American tries to be funny on stage, you know it should be funny, it is not, but still you feel obliged to laugh – sadly the laughing points would have been the only serious points, but alas amidst all the laughter never developed. I was shocked to see this woman being a Franz Boas professor, must be turning in grave this poor chap. – Saying this, I have never read her books, so this is based solely on what she did not manage at all to explain today – but certainly, this performance was the opposite of arousing interest. The concept seems shallow, unthought through, intellectually unexciting. As a female anthropologist I felt double shame, for the discipline and women in it. Way to make itself irrelevant in contemporary world where anthropology is most needed.