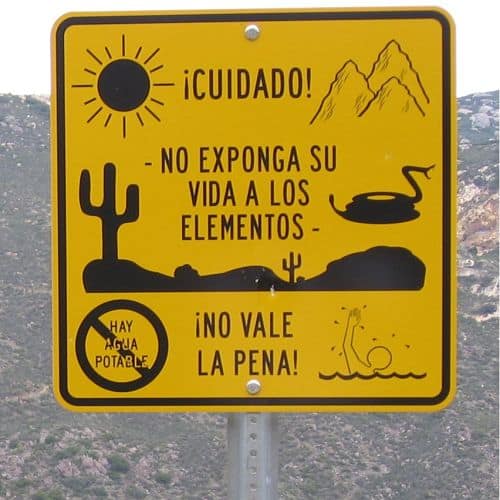

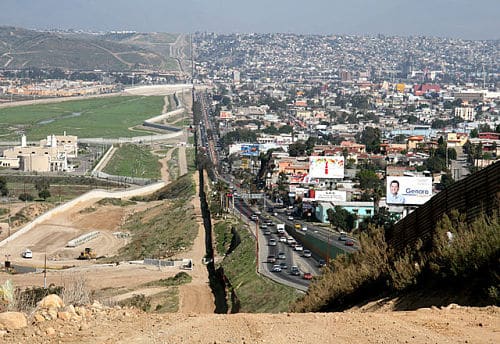

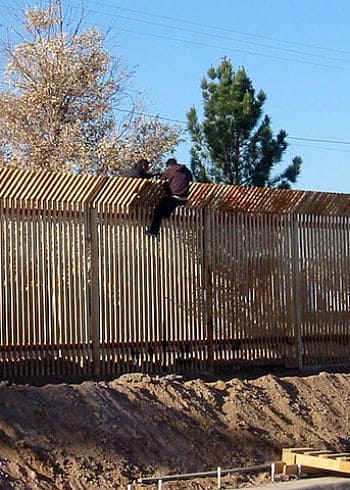

Clandestine migration across the US-Mexico border is a dangerous process. Not only must one avoid detection by US authorities, but also encounters with bandits known as bajadores, drug smugglers, and venomous snakes. Migrants must also endure a long, difficult walk, the extreme temperatures of the Sonoran Desert, and the lack of water in the area.

Exposure to the elements, most notably hyperthermia, is the leading cause of migrant death in southern Arizona, with over 2,413 known migrant deaths occurring between FY 1990 and 2013 in this US state alone. Choosing a reliable, trustworthy guide is paramount in ensuring one’s safety, avoiding detection by US authorities, and successfully reaching one’s desired destination.

But how can scholars evaluate the quality of services in informal economies? What are the criteria used for judging people’s satisfaction with these types of services? In the context of unauthorized migration, the media and some academics tend to portray human smugglers as subjects without a moral compass, often situated on two extreme poles as either ‘villains’ or ‘heroes’.

It is important to develop a richer perspective on smuggling, one that takes into account the diversity of contexts and individual experiences among actors on both sides of this transaction – that is, smuggling facilitators and those who rely on their services. Our research examines the factors associated with migrants’ satisfaction with the services provided by their smugglers, known locally as coyotes. We also examine whether or not migrants would recommend the same smuggler to a family member or close friend.

We examine migrants’ satisfaction with and recommendations of coyotes by drawing on data gathered in the second wave of the Migration Border Crossing Study (MBCS). The MBCS is a unique data source consisting of surveys with Mexican migrants in five different border cities and Mexico DF. In order to be eligible to participate in the MBCS, migrants must have attempted a border crossing in the post-9/11 era, been apprehended by any US authority (either while crossing or in their destination community), and repatriated to Mexico within a month prior to being surveyed.

For this particular analysis, we focused exclusively on the 600 respondents who most recently crossed with a coyote within five years of being surveyed. And while all MBCS respondents had been removed from the US, the sample does include a mix of people who successfully made it to their desired destination as well as who had not.

What satisfies the smuggled?

Overall, we find that there is little variation in coyote satisfaction according to demographic characteristics or smuggling fees. Rather, satisfaction is best explained by instrumental outcomes and effective protection from risky situations.

For instance, migrants who successfully reached their desired US destination were more likely to report satisfaction, while border crossers who were abandoned or physically mistreated by traveling companions, or witnessed the physical mistreatment or abandonment of others, were less likely to report satisfaction with their coyote.

However, our research also uncovers an interesting relationship between ‘satisfaction’ and ‘recommending’ a coyote to family/friends. First and foremost, and unsurprisingly, people who were unsatisfied with their coyotes were overwhelmingly less likely to recommend them to a family member or friend. However, this relationship is not as straightforward for people who reported satisfaction with their coyote.

For example, 68% of MBCS respondents who used the services of a coyote during their most recent crossing attempt were satisfied with their guide. When asked whether or not they would recommend their coyote to a family member or friend, only 38% of respondents indicated that they would. Furthermore, among the migrants who stated that they were satisfied with the services provided by their coyotes, only 53% would recommend their guide to a loved one.

Why would someone be satisfied and yet not be willing to provide a recommendation?

This disconnect represents one of the core challenges for evaluating the relationships between clandestine service providers and their clientele. First, the coyote-migrant relationship has some unique characteristics that are not wholly transferable to say, drug users and drug dealers. While both migrants and drug users rely on a certain level of trust that operates outside of the normal guarantees of society, entrusting one’s physical wellbeing to a guide is different from the more transactional nature of most illegal services.

A migrant’s well-being and safety are the direct responsibility of the coyote, not just their delivery to a foreign country. There are no third party enforcers in the clandestine world that can protect one from various forms of victimization or bad faith actors.

For example, in the formal economy, if someone does not deliver goods or services that were paid for there is generally some legal recourse. However, in the informal economy, the only recourse is violence.

We found some important differences in what drives people’s logic for a satisfactory interaction, versus why they would or would not give a recommendation. Namely, satisfaction is a product of instrumental factors (e.g., success, abandonment etc.), while a recommendation has a more expressive, qualitative dimension.

As noted above, people who were satisfied with their coyote were much more likely to have successfully crossed the border. Conversely, those who had been abandoned or witnessed others be abandoned were much less likely to be satisfied. However, when analyzing open-ended responses about whether people would or would not recommend their guides, they relied heavily on the frames of trust, treatment, and smuggler conduct.

This is an important difference that opens up new questions about migration and smuggling as a whole. Because the smuggler-migrant relationship is one born out of necessity, the need to cross the border likely outweighs issues of treatment, trust or quality; however, when thinking about subjecting a loved one to the same treatment, these issues become far more important.

For migrants, especially in the predominantly male Mexican population we surveyed, the expectations of good treatment are rather low. It is important to distinguish between the cold calculations born out of the desperation to cross a border illegally, subjecting oneself to extreme danger and even risk of death, and the idea of entrusting a loved one’s well-being to this person, a person whose motives and actions are outside of anyone’s control.

Our co-producer openDemocracy offers more food for thought on human smuggling:

- Beyond common-sense notions of human smuggling in the Americas, by SOLEDAD ÁLVAREZ-VELASCO and MARTHA RUIZ

- Smuggling as social negotiation: pathways of Central American migrants in Mexico, by YAATSIL GUEVARA GONZÁLEZ

- The call to become a smuggler, by LUIGI ACHILLI

- Precarious livelihoods in eastern Indonesia: of fishermen and people smugglers, by

- Governing migrant smuggling: a criminality approach is not sufficient, by ANNA TRIANDAFYLLIDOU

- The struggle of mobility: organising high-risk migration from the Horn of Africa, by TEKALIGN AYALEW MENGISTE

- Communities of smugglers and the smuggled, by NASSIM MAJIDI

**********

Featured image: Border Patrol sign in California warning “Caution! Do not expose your life to the elements. It’s not worth it!”, via Wikimedia Commons