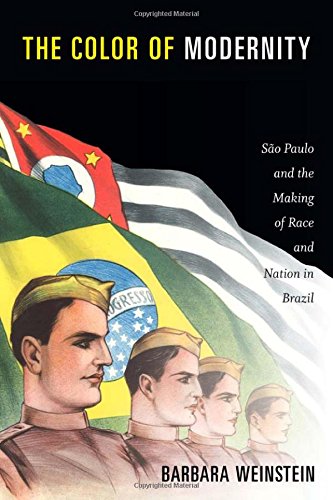

The Color of Modernity. São Paulo and the Making of Race and Nation in Brazil is an ambitious effort to rethink the formation of a regional identity and perceptions of race in São Paulo from the 1920s through the 1950s. Barbara Weinstein, Silver professor of Latin American and Caribbean history at New York University, examines how residents of São Paulo constructed a paulista identity associated with “whiteness” in opposition to other areas of Brazil and how this affected long-term processes of modernity, progress and democratization.

This racialized regionalism reproduced regional inequalities, Weinstein argues, as São Paulo became synonymous with prosperity, while Brazil’s Northeast, a region plagued by drought and poverty, came to be represented as backward and São Paulo’s racial “Other.”

This view of regional difference later led to development policies that intensified these inequalities and hindered democratization.

The book centers on two “special occasions” in the 20th century that contributed to “paulista exceptionalism”: the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution and 1954’s IV Centenário, the quadricentennial of São Paulo’s founding. In a diligent and exhaustive manner, Weinstein relies on a large variety of sources including memoirs, press, music, films, photography, books, graphic design, exhibitions and staged spectacles for illuminating multiple perspectives and narratives that underline the constituency and representation of these particular historical moments.

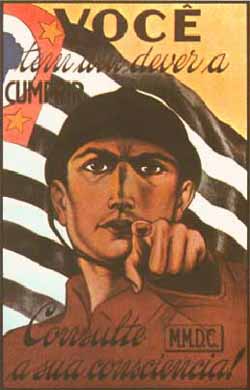

Consequently, the book is divided into two parts. The first one, “The War of São Paulo” (pp. 27-217) comes after the short introduction and examines the civil war that took place during the initial period of the region’s economic and demographic growth following the coffee boom in the 1920s. In 1932, after gaucho politician Getúlio Vargas and his military had seized power through a coup d’état (1930), the state of São Paulo risked losing its autonomy and its citizens were mobilized for war against the federal government. Weinstein highlights the racist arguments underlying the conflict by showing that the Constitutionalist Campaign was discursively constructed as being white, male, and middle class, while reality was much more complex: The battalions included immigrants, proletarians, artists and Afrobrazilians, who joined the war through the Legião Negra, a self-identified all-back battalion. And finally, although women had supported the movement as sewers, nurses or hard fighting combatants, they were generally portrayed in a depoliticizing manner as sober, civic-minded white housewives. The final chapter of this first part highlights regional counter-discourses to this narrative of paulista superiority and concentrates especially on the press from Brazil’s Northeast, that was imagined to be Sao Paulo’s black, underdeveloped, poverty-stricken, miserable, folkloric counterpart.

The book’s second part, “Commemorating São Paulo” (pp. 221- 343) deals with the massive program of commemorations, spectacles, and cultural events that marked the four hundredth anniversary of Sao Paulo’s 1554 founding during the final months of 1954. Weinstein here focuses on the conflicts within and between different commissions, politicians, architects, journalists, artists, and the wider public that struggled over competing ideas how to present the city, the region or the nation – not only towards the ‘povo’, but also towards a larger, global audience. The event was supposed to teach a sense of the city’s particularities, its modernity and future promises during a political period that was shaped by (middle-class) pessimism due to political instability, rising costs of living, factory shutdowns, loss of wages and, finally, also the suicide of Getúlio Vargas in August 1954, who had returned to power in 1951 as the elected president of Brazil, which interrupted the inauguration of the memorial event for two weeks.

Different from the 1930s, the triumph – or myth – of racial democracy by that time constituted the dominant discourse of national identity, which had a particular impact on questions how ‘history’ should be represented in public pedagogy. The racialized connotation of this event becomes most obvious in the debate over a monument for the ‘mãe preta’, the black mother, which was included rather hesitantly into the event’s official programme. Interestingly, Weinstein also reflects on how the constitutionalist revolution of 1932 was included into the festivities, where it received a ‘glossy representation’ (p. 317), representing it as a moment of social unity and harmony. In fact it was in 1954 that ‘9 de Julho’, the beginning of the uprising in 1932, achieved its particular meaning for the constitution of the paulistinidade, being interpreted as a progressive and heroic ‘civic moment’ produced by the educated white middle-class.

Different from the 1930s, the triumph – or myth – of racial democracy by that time constituted the dominant discourse of national identity, which had a particular impact on questions how ‘history’ should be represented in public pedagogy. The racialized connotation of this event becomes most obvious in the debate over a monument for the ‘mãe preta’, the black mother, which was included rather hesitantly into the event’s official programme. Interestingly, Weinstein also reflects on how the constitutionalist revolution of 1932 was included into the festivities, where it received a ‘glossy representation’ (p. 317), representing it as a moment of social unity and harmony. In fact it was in 1954 that ‘9 de Julho’, the beginning of the uprising in 1932, achieved its particular meaning for the constitution of the paulistinidade, being interpreted as a progressive and heroic ‘civic moment’ produced by the educated white middle-class.

Weinstein clearly shows that the particular conditions of the present are decisive for understanding how historical events are remembered and commemorated and how they not only serve contemporary political and populist interests, but also visions of the future.

In this case, the memory of the Constitutionalist Revolution had been re-signified as a struggle for democracy. The negative image of Brazilian regions other than São Paulo served the revival of hierarchies, as these were designated as a locus of political extremism and disorder. Curiously, any reference to an alleged ‘communist threat’ was absent from the commemorations, although the 1950s were also a time of Cold War and strong anticommunism.

In the epilogue and conclusion (pp. 331-343) Weinstein reflects on a more theoretical level on the question of historical continuities and critically examines a potential connection between the events in 1932, 1954 and 1963, when the Brazilian military seized power and installed 21 years of authoritarian rule. She argues that these events, albeit their enormous differences, and the discourses on regional superiority communicated therein, made certain political positions ‘thinkable’ among certain sectors of society; they do not only reflect, but actively shape identities in the interests of the respective political moment.

The Color of Modernity provides us with a fine-grained representation of history that teaches us about the particularities of regionalism, nationalism, but also modernity, meanings of race and democracy in Brazil.

Barbara Weinstein does not include a separate chapter that would describe or defend her theoretical framework or methodological choices at length – these reflections are rather part and parcel of her detailed analysis. I recommend this book to any (informed) reader, who is not only interested in the particularities of 20th century Brazil, but who also wants to understand how history and histories are done through the continuity of time.

Weinstein, Barbara. 2015. The Color of Modernity. São Paulo and the Making of Race and Nation in Brazil. Durham and London: Duke University Press. 472 pp. Pb: 29.95$. ISBN: 978-0-8223-5777-3

**********

Featured image (cropped): ‘São Paulo’ by Marcelo Druck, flickr, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)