Empowering the Next Generation of Digital, Public Anthropologists

In Yorkshire, England with a backdrop of bleating sheep and patchwork fields, archaeologists-in-training investigate, explore, and experience WW1-era military barracks, or what remains of them. They guide school children armed with trowels, who assault the carefully excavated trenches. Grey-haired, wind-weathered residents of nearby hamlets peer over the barbed fence, telling stories that are collected, queried, and valued. Apps are created. Interactive exhibits crafted. Articles written. This is a classroom.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, in Newfoundland, Canada, students work in a bright lab where once clean lab coats are patterned with dust, dirt, sediment and soil that is over 4000 years old. There are no artifacts to be found, but those are not what they are looking for. Their trowel is a microscope and the excavation takes place within a test tube. This is archaeology on a microscale. They are mentored, and they mentor each other; they design research and apply for grants; and they are successful. Sometimes they aren’t. Twice a year they trade their lab coats for dress shirts and present their work at conferences. This too, is a classroom.

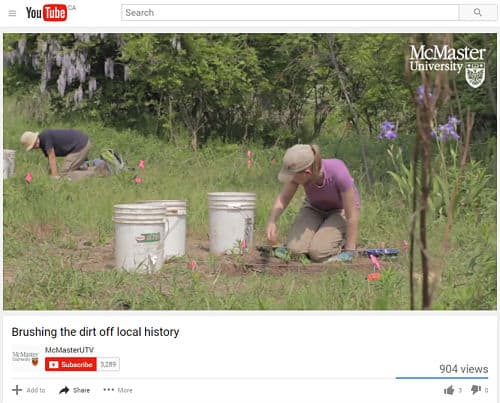

Elsewhere, in one of the most densely populated regions of Canada, connected to the whole gamut of humanity and simultaneously swallowed up by urban anonymity, there is a classroom in the basement of an industrial park that morphs into a digital framework, a virtual network of knowledge, dialogue, and inspiration. In this basement, over 50 years of archaeological practice resulted in the accumulation of over half a million artifacts, and this number continues to grow. Throughout the summer, students become research assistants who, through meticulous data entry transform forgotten collections by placing them into a digital context that links, sustains and conserves the past and connects communities to their heritage.

Around the world, students Instagram life in the #lab and their daily adventures in #fieldwork. Facebook groups are formed to share their funny pictures, organize #nerdparties, and coffee shop study sessions (#allnighter #studentlife). They blog their assignments, making anthropology visible and accessible in a much wider world. Their ideas are retweeted, commented on, and drawn into increasingly digital formats. The atmosphere is charged with ideas, and sometimes dreams of meeting an anthropologist who has inspired them. Some emerging anthropologists would #fangirl at the chance to get a selfie with Mead, Boaz, Benedict, Goodall, Schepper-Huges, Hodder, Harroway, Parker-Pearson, Joyce. This is a classroom that is unsupervised. It operates 24 hours a day, on phones, tablets and laptops, from bunkbeds, busses, kitchen tables, libraries and anywhere and everywhere with wi-fi and an idea.

Students are building a new classroom, one that doesn’t have any desks.

Together with instructors, teaching assistants and staff, they are part of a movement that is crafting a new student and a new way to learn. These dynamic, open classrooms stand in contrast to the traditionally insulated, static campuses of universities. The seasonal ceremonies of exams, ritual cramming, consumption and re-distribution of high-caffeine, sugar-based feasts, and the sacred arts of writing essays, secreted away to sealed department closets and filing cabinets, or worse, shredders and recycling bins, are entrenched in the timeless traditions that built the monolithic ivory towers of academia.

The obscurity of campuses is complemented by the heavy financial burdens of tuition and textbook costs today that persistently exclude more than they include in the revered process of bestowing degrees, scrolls of success which, in the end, may or may not prove to be fruitful. These ceremonies, regalia, and symbols have lost their meaning for many students. No one cares about who carries the scepter at graduation; #graduation is the new scepter. This is what the public sees. They do not see the honours thesis, printed and bound though it may be, nor do they see the mountains of transcribed interview notes, library books, and archived drafts. The public sees the blogs, the selfies, the tweets. And although social media might not reach everyone (#whatsafacebook #dothetwitter), there’s email, and printers. And someone who holds their phone up to show a friend, who tells their neighbour, who discusses it with their community group. And this is how anthropology is ‘going viral’ today.

#WhatsaPublicAnthropology

For universities to truly move beyond what has been criticised as cultish, or even colonial, to uphold the tenants of diversity, access and impact, the very concept of the classroom needs to be revolutionised. And for anthropology to take the next step to advance the pioneering works of public engagement, which transformed academic research in the twentieth century (#tbt), higher education needs to be designed to empower twenty-first century anthropologists. How can we provide the next generation with the tools, passion, and confidence to have public impact, if their education is, at its core, insular and inward-looking?

The answer lies in opening classrooms, physically and virtually, to take students, teachers and research public.

The generation gap is never clearer in academia than when professors are overheard bemoaning the fact that their students don’t do the assigned readings (but ‘waste hours’ on Reddit), or are consumed with chatting online, when they won’t raise their hand in class. There is no end of clunky learning technologies that have been rolled out to engage these ‘digital natives’ that seem to only result in exacerbating the problem. Video captures of lectures, expensive hand-held devices to quiz and probe students, and private discussion boards on unwieldy web-based services have not produced the creative, engaged, critical thinkers that technology companies sold us on. When a student clicks yes or no to a question, or ‘logs on’ to fill out a multiple choice quiz, it removes their voice. It denies them the fluidity and flexibility to develop ideas and express themselves, work through problems and make connections to a world beyond the ‘digital learning environment’. These are just some of the inherent skills that are learned through anthropology and the foundations required to build strong, thoughtful, public anthropologists.

The truth is that these endeavours are still so far removed from the reality of anthropology that they cannot stimulate the public researchers of the future.

Modernising learning should be about augmenting reality, not isolating students from it even further. This doesn’t mean strapping students into virtual reality goggles that bring them three-dimensional lecture experiences from the comfort of home (#ArmchairAnthropology) or writing lectures as BuzzFeed articles, or rather ‘listicles’ that can teach you ‘Ten things you should know about cultural appropriation’. Rather, it should be about giving students the chance to engage with experiences akin to those that are used in the careers they are preparing for.

Dynamic applications of technology have already infiltrated anthropological research – there are tablets for fieldwork, apps for taking ethnographic notes, social media outlets for building community collaborations, and printers that reproduce ancient artifacts in a matter of hours. To address issues of inclusion, access to the equipment necessary to engage in these technologies also needs to be available to all students. Moving away from the outmoded concept of the ‘digital native’, there needs to be recognition of the fact that not all students have smart phones glued to their palms. At the same time, most employers expect a high level of digital literacy, particularly from younger generations. Digital anthropology training is therefore not solely about public engagement, but also ensuring that all students have equal opportunity to build the skills necessary for employment.

Removing university students from these realities is a disservice to them, to the societies that fund research in the social sciences, and to the future of the discipline. So too is the practice of keeping students out of the public realm until they are ‘experienced enough’ to handle it. Let’s face it – students are really good at public relations. They know how to talk to people, and sometimes they even enjoy it. They do a brilliant job at being real (sometimes too good of a job, but #NoOneIsPerfect). Whether they go out to the community in person, or collaborate with them digitally, they make anthropology accessible, fun, and inspiring. They are enthusiastic, approachable and down-to-earth. Dismantling the public image of anthropology, they also engage youth and secondary school students and inspire the future, future of the discipline. So why not make them more than just #instafamous, but actually active agents in the public anthropology that we strive for?

#StepItUp

It can start small: a blog-based assignment, writing an insightful 140-character tweet that captures an essay or research project’s thesis, or crafting a poster or an infographic. Incorporating small changes to course frameworks and classroom dynamics break the ice for students and professors alike, who are often nervous about taking their work public. Teaching and learning are deeply personal, and the shift from the security and insulation of the ivory tower to the unpredictable and exposed open classroom can feel like working in a fishbowl. But progressive and collaborative development of public engagement skills serve to build confidence and competence in anthropologists of all levels.

Recording podcasts or vlogs instead of or alongside of in-class presentations expands audiences and opportunities for feedback. Participating in (or even organizing) museum open days and community walks transforms students into teachers. Storifying events, ethnographies, or anthropological discourse can be used as both an analytical tool and a way of communicating findings. Creating interactive web platforms disseminates research findings written for general audiences. Building digital maps and apps with communities showcases and preserves culture, memories and heritage. As students amass portfolios of projects that demonstrate their skills and qualifications, they also contribute to quality anthropological research that confronts mystery, myth and pseudoscience. If students have already mastered digital platforms by using software like Prezzi to show their results, Qgis to created layered maps and Piktochart to make infographics, the next challenge might be to design their own anthro-technology.

Let’s be bold – imagine if classes were held in public spaces of campuses, libraries and parks, where any interested community members and students can be invited to join in, earn credit or just enjoy.

Cyber hangouts and ‘unconferences’ can be used to further break down barriers and build collaborations that spill out of the university and gain momentum with each new connection. These approaches engage students in projects and networks that will provide them with lifelong opportunities, rather than a short semester of focus.

Ultimately, the classroom can be anywhere and anything. Today, whether enrolled at a university or not, we can all carry the classroom of anthropology with us. Instead of waiting for film roles to be developed, in an instant an anthropological moment is captured on a phone, messaged to a friend, emailed to colleague or connected to networks of images in virtual galleries. Anyone with a smart phone or tablet can record an interview or a cultural event at any time. Rather than wait years for a book to be published, data can be shared fresh from the field.

This also means that we need to update how we teach students about the act of doing anthropology, and how we conceptualise it ourselves. Suddenly courses begin with photo release forms and discussions of social media usage alongside the traditional spiel of academic dishonesty. New definitions of academic integrity and research need to be considered.

The ethics of digital anthropology are transforming day to day, and we need to collaborate as much on responsible media usage as on the subjects of anthropological research.

We also need to understand and address boundaries.

#SorryNotSorry

This very process, however, builds accountability into the higher education system, which has been sorely lacking from traditional university programs. Whenever anthropologists write or speak about research, their words, ideas, and conclusions have impact. Sometimes they create positive changes, galvanise communities, advocate for them. But sometimes they can be hurtful, confusing, or even oppressive. Anthropology has a deeply concerning colonial history of disempowering cultural groups, and the legacies from this troublesome past create frequent pitfalls today. Public anthropology is about healing those fissures that have created divides between researchers and communities by building collaborative relationships, recognizing other voices and authorities, and creating space for alternative ways of knowing. However, as soon as we close students off in classrooms and the practice of private essays and exams, the sense of duty and responsibility dissipate.

Opening classrooms does not simply mean setting students loose to wreak havoc on the world. These experiences have to be complemented with frank and insightful discussions of these histories of tension, self-critique and reflection, and structured opportunities to take action. The good thing is that lessons in decolonising language come naturally when students’ words are actually going to impact people. Complex issues in ethics, politics and practice are best explored and understood through application.

However, there are also broader questions that remain, blurring the lines of the various ‘publics’ in anthropology. How far do ethical policies stretch? If an anthropologist tweets on their own time, are they obligated to follow the ethical frameworks of universities and professional associations? Does public anthropology mean there is no such thing as ‘private’ for the anthropologist? Who is responsible for mediating and shaping students’ use of social media on anthropological (and non-anthropological) subjects? As digital media advances, and research is crafted to be more and more centred on the public, the visible, and the impactful, the scales of public expand to complicate long-standing ethical and political implications of research.

We are all #ModernDayMargaretMeads

The current challenge, then, is to redefine public anthropology, and who gets to do it. Part of that is weaving students into the process; the other part is developing teaching and research alongside and in combination with modern technologies. Reconceptualising higher education from structured, closed classrooms, to open, accessible and inclusive physical and digital environments for engagement, innovation, and advocacy, is at the core.

This isn’t about gimmicks; it isn’t about a publicity stunt, but rather embracing our public responsibility.

The responsibility doesn’t simply fall to university instructors, either. Opening up classrooms only really works if there are people on the other side to engage with students, share their perspectives and collaborate. If public anthropology is the ideal, then we all need to be part of the discourse, read blogs, listen to podcasts, be an active voice in comments sections. Be critical of information, news headlines, biases and discourse, and demand better. Take opportunities to collaborate on projects, infiltrate classrooms, build bridges between campuses and communities, near and far. We all need to be part of defining and creating what is relevant, in anthropology and beyond.

Margaret Mead, one of the earliest public anthropologists, measured “success in terms of the contributions an individual makes to her or his fellow human beings.” Although she didn’t tweet her vision for anthropology, it embraced open dialogue, impact, and cooperation. Today, what might start with a hashtag, a poster in a coffee shop about a public lecture, a field course with a syllabus defined by community groups, a free, open access book, might achieve the goal of anthropology, as defined by Ruth Benedict: making the world safe for human differences. With new visions of what anthropology could be, how it is taught, and to whom, could we even go one step further than these early public anthropologists imagined, and make the world thrive on human difference? #DareToDream