Allegra is delighted to welcome on board Judith Beyer as a Review Editor! Judith is an anthropologist specializing in legal and political anthropology. She is lecturer at the Department for Social and Cultural Anthropology at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. Prior to that, she held a postdoctoral position at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. Her current research investigates land and property regimes of religious minorities in Myanmar (Burma), and it is among the first long-term anthropological projects to trace the legal, political and social changes that the formerly isolated Southeast Asian country is currently undergoing.

Allegra: Before you started working in Southeast Asia, you wrote a PhD on “Legal pluralism and the ordering of everyday life in Kyrgyzstan.” Can you tell us about your doctoral research and your interest in political and legal anthropology more broadly?

My interest in legal and political anthropology relates to the observation that human action is always political action and that at some point, “law” always seems to play a role. “Law” is the elephant in the room – it usurps the right to define, but escapes definition. To me, the concept of “law” is similar to that of “culture” – equally difficult to pin down, but as opalescent.

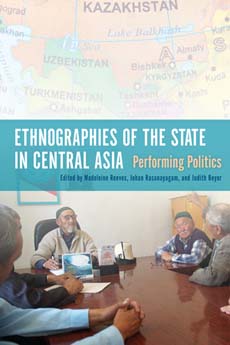

The articles in the book focus on how politics in Central Asia is performed and how, as a result, “the state” is enacted into being. We look at political phantasies, the material aspect of state-making, the dialogical roles of authorities and audiences in creating images of the state and the moral positionings that occur.

We explore “the political” as an on-going reinvention that continues to be shaped by Soviet heritage, but has acquired its very distinct character, which is derived from the fact that all post-Soviet Central Asian states are very new creations. People’s efforts at constructing distinct national ideologies and narratives of nationhood have let us inquire into issues of legitimacy and representation. Central Asian political imaginaries, we argue, should be used comparatively and introduced to other colonial and post-colonial debates from which the region is still absent.

How about your current research interests? How did you move (intellectually) from Central Asia to Myanmar?

Within the German academic system, it is still considered important to broaden your regional expertise by focussing on a different field site for your “second book.” I have had a long-standing interest in Myanmar (Burma), but the country was even more locked in the past than those of the Soviet Union. When I went for a first trip in 2009, after the government had signalled willingness to “open up”, I was immediately taken in by its extremes: the beauty of the place on the one hand, the shy curiosity of the people to whom foreigners were still a rare sight, but also the paranoia of being observed on the other hand – as well as the visible reminders on billboards and in newspapers that “all enemies of the state will be crushed.” I started my fieldwork in December 2012 and have spent a total of six months in the country so far. My project investigates the changing situation of religious minorities in the former capital Yangon. Yangon is a port city and a metropolis, and it was quite a challenge for me after having worked in rural Kyrgyzstan, but I am getting used to a different kind of anthropological research, which is a great opportunity.

I investigate how non-Buddhist religious communities manage to secure, expand and administer their land and property, most of which is located in the downtown area. In the last two years, this particular area has witnessed an incredible increase in value. Buying property there is now more expensive than in New York City. This development is spurred by an unprecedented influx of foreigners in search of business or leisure, and citizens from the countryside in search of work. Not only is there an increasing lack of living space, but also a property market regulated by (former) military government officials who expropriated valuable property, often from religious minorities, in the 1960s. In this volatile economic, legal, and political climate, which is also pervaded by a pernicious ethno-Buddhist-nationalist discourse aimed at the exclusion of others, I investigate how these religions communities sustain themselves.

By which books or authors have you recently been particularly inspired?

Three books about bureaucracy: Kregg Hetherington’s Guerilla Auditors (2011), Akhil Gupta’s Red Tape (2012) and Matthew S. Hull’s Government of Paper (2012): I can directly relate some of their arguments to my field research in Yangon. Plus, they are all well written and fascinating to read.

What persuaded you to take up this position as Allegra Reviews editor and what kind of plans do you have for it?

I like the idea of publishing timely things in a timely fashion. And while there is no official “blind peer review” on platforms like Allegra, for me there simply is no alternative to open access anymore – it’s fast, free, and fair and I enjoy engaging in conversations with people directly after having published an article – something which is rarely happening with classical publications these days. Plus, Allegra is fun and I am looking forward to joining a team of bright people.

We will set up a special Reviews section on the website soon and I will post a list of relevant publications there. For now, you might want to look out for our upcoming publication list on Islam next week. Some of these books we would like our readers to review. If you are interested in writing a review for Allegra, you can contact me at reviews@allegralaboratory.net

I hope to help make Allegra Review a key source when it comes to reviewing current and classic works on and beyond legal anthropology.

Read our previous book reviews here:

Lori Allen.2013. The Rise and Fall of Human Rights: Cynicism and Politics in Occupied Palestine. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. Reviewed by Tobias Kelly, University of Edinburgh.

Michael D. Jackson. 2012. The Other Shore: Essays on writers and writing. University of California Press, 205pp. Reviewed by Fiona Murphy.

De Lauri, Antonio, ed., 2013, War, Antropologia, Vol. 16, Milan.135 pp. Reviewed by Luca Nevola.

Anonymous. ‘6‘. 2013. Zones Sensibles. Reviewed by Julie Billaud.