Mahmoud Dowlatabadi is an acclaimed and respected writer in Iran. A post stamp has recently been produced in his honor. One of his latest novels, The Colonel, was published in 2009 in German, and later translated in several countries among which the UK, the US, France, etc. In Iran, a samizdat version of the novel is circulating in the black market since the Summer 2014, but the author has vigorously disowned the book as being a fake and a re-translation back from German that ruins his prose and literary texture – Dowlatabadi’s “signature”. In the meanwhile, the original manuscript entitled The Downfall of the Colonel, is waiting since 2008 for a publishing authorization at the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. As of November 2014, the book was still under review at the Ministry, reported the Tehran Times, according to which the novel « is about the life of an Iranian colonel who recalls his memories of families and friends in solitude. »

The Colonel

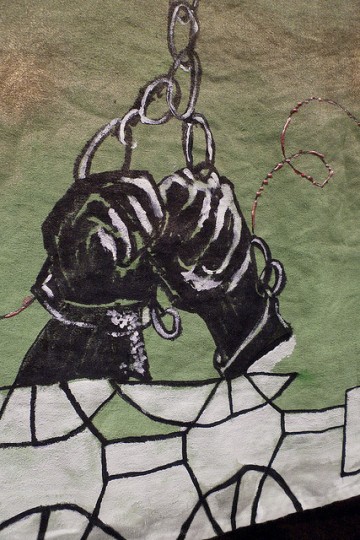

Well, not exactly. The Colonel is about a retired army man, who is summoned one rainy night at the prison office, in order to retrieve the tortured body of his 14 years old daughter Parvaneh. She was arrested a few days before by the Guardians of the Revolution, in possession of leftist leaflets. Now, the colonel must retrieve her body and bury her before dawn. The scene takes place right after the revolution, during the cruel years of the war against Iraq and political repression. It is not the first time that the colonel loses a child: before Parvaneh, one of his son was killed in the revolutionary insurrections, and another one “martyred” on the war front.

Under the pouring rain, an ambulance drives the old colonel and his daughter’s body to the cemetery, accompanied by two police officers who supervise the operations. At the mortuary, the colonel realizes he has no tools to dig the grave and no help to wash the body. He returns back home in the rain to ask the help of his older son Amir. Amir is living in the house’s basement and doesn’t speak anymore, doesn’t go out anymore. He dwells in his nightmarish past, in the torture chambers of the Shah’s political prisons. “As if totally unaffected by the news, as if struggling with a geometry problem: ‘Wasn’t she too young to be hanged?’ ” (Dowlatabadi 2012: 40), replies Amir, who refuses to help. The colonel then sets for his daughter’s house. His daughter, Farzaneh, is married to the ambitious, opportunistic Qorbani: a Hezbollah militiaman who – according to the colonel’s daughter – “smells of blood” when he comes back from prison in the early morning. In the early days of the Revolution, Qorbani was parading his brother-in-law Amir, the heroic communist opponent to the Shah, throughout the town. Now that the wind has turned, he does not spare his contempt and sarcasms for his embarrassing in-laws. Rebuffed by his son-in-law, the colonel borrows a pick and shovel from his daughter and heads back to the cemetery in the rainy night: he does not tell Farzaneh about her sister’s death.

But how to wash the body alone and dig the grave in these late hours of the night? In the mortuary, the colonel sees his late wife, dressed in a shroud and looking alive, except her eyes that glow red “like two bowls of blood”. Years before the events that whipped out the colonel’s children, his wife died by his own hand. Suspecting her of cheating on him, the colonel has murdered her with a knife – a killing for which he went unpunished. Now, in the mortuary, his wife wants to wash their younger daughter’s body and enshrine it. Does this happen? Are the colonel’s fantasies taking the lead at the most unbearable moment, where the soaked old man has no other choice than to perform the washing himself, or let his daughter being buried without a shroud? It is the policemen who help the weak colonel to dig-up the grave in the dark. They remind him that he is not “allowed to put anything on the gravestone”. They finish the work as the story becomes a tale, and the author’s tears merge with that of the colonel, washed by the pouring rain:

“We’re obliged to dig our own children’s graves, but what’s even more shocking is that these crimes are creating a future in which there is no place for truth and human decency. Nobody dares to speak the truth any more. Oh, my poor children… we’re burying you, but you should realise that we are also digging a grave for our future. Can you hear me?” (Dowlatabadi 2012: 72)

The experiences of post-revolution violence in Iran long remained absent from literature or cinema. Farokh Sarkouhi has documented this silence through the most striking event in State violence: the massacres of several thousands of political prisoners in 1988. He states that in Iran during the years 1988-1996, although the events were known in the intellectual circles, they were only mentioned in one short story, one drawings exhibit, and three news articles (one of which covered the drawing exhibit). The artists’ notable, long-lasting silence is both an effect and a cause for the fact that the multi-layered history of violence, which is literally at the foundation of the current Iranian State, has not penetrated collective memory. A process of inclusion of the “public secret” (Taussig 1999) into spheres of acknowledgement and collective representations of the past is slowly setting in motion since the late years 2000.

These fictions and non-fictions tell about a reality that organized both the mechanisms of violence and the binding of silence: the treatment of opponents not so much in their lives as through their deaths. The colonel’s nightmarish night of burial recounts a dislocation of funerary rites. Secret, confiscated, suppressed burials are a recurrent scheme and a matrix in the narratives of State violence in the 1980s. Asking why these episodes are so important in the framing of memory sheds a new light on the effects and mechanisms of violence – as politics of death. The fact that neither of these narratives has yet been published in Iran says a lot about the collective silence instituted and maintained through these politics. The Downfall of the Colonel’s yet to come official, authorized publication inside the country would be an unprecedented development in the disputed writings of the past.

Manuscripts in a drawer: a history of violence

Dowlatabadi wrote The Colonel in the early 1980s, at the time of the events described in the novel, when his friends and fellow intellectuals were executed, and himself summoned for interrogation and warned not to teach at the university anymore. Then, he hid the manuscript in a drawer for decades, in order to be able to go on with his writing and publish notably his three-volume literary success, Bygone Days of the Elderly. In those years, another manuscript was laying quiet in the dust of a drawer. It was the testimony that my grandfather left for us, recalling in details the arrest, imprisonment and execution of two of his daughters: my mother Fatemeh Zarei, and my aunt Fataneh Zarei. Twenty years after his own death, my grandfather’s testimony was published, first in French in 2011, then in English under the title Aziz’s Notebook. At the Hearth of the Iranian Revolution, and finally, in Persian by H&S publishing house in London.

At the time Dowlatabadi was writing the story of The Colonel, another “broken” old man, my grandfather, was summoned, for real, to Shahrak prison in Bandar-Abbas to receive the news of his daughter’s execution and retrieve her body. In his testimony, my grandfather recalls these moments, taking us in the judges’ offices to sign a paper stating he will remain silent, in the morgue that is ungoing a power cut, in the ambulance, in the mortuary, where his wife tries to get a glimpse of her late daughter’s body before it is enshrined, in order to find out what became of the child she was bearing when she was arrested. The events don’t take place in the night and the rain, but in full day’s light, under the unbearable sun of the South. And “melting like snow in the sun”, my grandfather writes, “the large crowd that was thronging the door dispersed” when he came out of the prison with the belongings of his daughter Fataneh and a piece of paper in is hand. “But they were right” he adds, “they did not dare sympathise as they knew that if they expressed their feelings, they would be endangering their children in prison” (Makaremi 2013: 30).

The House of the Mosque

The two narratives write down in secret a history of violence yet to be uncovered, and their authors know that they do not write for the time being. But both narrate this history of violence through one powerful, haunting image: in the wheels of a cruel administrative power, a father must burry his own child, alone and out of sight. This image, which seems to encapsulate the nature and texture of a decade of political violence, is also present in another novel set against this backdrop. In The House by the Mosque published in 2005, Kader Abdollah tells the story of the Iranian Revolution through the saga of a family that owns a congregational mosque in a Northern city. Written in Dutch by an Iranian author who migrated in the Netherlands in 1989, the award-winning novel was translated in 27 languages, but not in Persian as of today.

In the fictional city of Senedjan, the keys of the Mosque belong to the Ghaemmaghami family, who hold the position of Imam from father to son. The life trajectories of the family members over decades tell in a fanciful, poetic mode, the deep changes brought about by waves of modernization and urbanization in the dictatorial regime of the Shah, and the modes of subjectivation that responded to these crises of culture and the self. The writer’s colorful yet large brush paints a world marked by the deep plasticity and uncertainty of both the power apparatuses and the evolving subjectivities. It retraces the streams that crystallize in a revolution Foucault identified as a “laboratory” of our contemporary word, “the most modern form of revolt, and the craziest” (Foucault 2001, p.716). It also provides the depth of field and perspective to sense the vehemence with which the revolution transformed the social world and disrupted individual destinies.

The Mosque that belonged to the family for centuries is confiscated by the new Islamic State, and the Imam issued from the family, dismissed, punished in public for his collaboration with the previous regime and replaced by a revolutionary Imam aligned with Khomeini’s theocratic line. The political Islam that seizes control over society and shapes the new State dislocates a traditional and religious order long in crisis.

We follow the turmoil through Aqa Jaan’s bewildered eyes – the head of the family, guardian of the Mosque’s keys and prominent merchant at the bazaar. Aqa Jaan’s son secretly joined a communist opposition movement. After the revolutionary guards raided a village known for its sympathy with communist guerrilla, Aqa Jaan is called to the prison’s office to retrieve the body of his son who has been executed overnight. The saga reaches a dramatic climax as the old father is driving from village to village with the body of his late son in the back of a pick-up, to look for a cemetery where he could bury him. But in each village, acquaintances lock themselves out of sight, and people stand at the cemetery’s gate to refuse him entry as they fear for their peace and the revolutionary guard’s reprisals. With the help of a cousin, Aqa Jaan finally digs a grave on a hill, under a tree, and buries his son there.

Death politics

These three stories are among the scarce body of works that directly speak about violence in post revolution Iran. They chose to narrate this era through a painful act of sepulcher that reverses the generational order of things. The acts of burial convey the texture and scope of post revolution violence: its experience, perceptions and impact on the social fabric.

In the narratives, the solitary and secret burial merges together different levels of the real, the imaginary and the symbolic.

The scene refers to events that took place in real life as Aziz’s testimony, and many others, recall. It serves as a dramatic matrix in the novels. And it symbolizes the kind of wounds that the experience of violence has left on the social body: a painful, unacceptable confrontation with inflicted deaths that break social taboos. We follow characters whose every step and action are extracted from a place of extreme exhaustion, stupor and modified perceptions – yet fathers do carry on their duty: they burry their children. As for the reasons of the execution, they seem to obey to a logic so impenetrable that it is concealed from the characters and the narrative. The acts, the stakes and the details of the crimes remain distant and obscure to all. The details of the violence exerted on the prisoners tellingly stay “off camera”. What these memories of violence retain are the families and the question of a sepulcher, what they sketch out is a phenomenology of collapse.

The common plots shared by these different narratives, written in ignorance of one another, draws closer attention to the organization of death. In the physical elimination of political opponents, the treatment of bodies has indeed had long lasting political and social effect in securing control and surveillance, in the short term, and shaping collective memory or a shortage of memory – that I call an “economy of silence” – on the long term.

Beyond the political cleansing of post-revolutionary society, the treatment reserved for the bodies of the dead – their being rendered invisible, their profanation, their exclusion – aimed for their symbolic and enduring removal from the social world.

As anthropologist Robert Hertz underscored in his analysis of funerary rites in the early 20th century, the management of the dead connects back to two essential dimensions, which are the position of the deceased in a family and community network, and the maintenance of the symbolic order through the respect of funerary rites. Across different cultures and historical periods, funerary rites involve a treatment of the body (cremation, burial, embalmment, etc.) and a temporality of mourning (the Shiva or “first seven days” in the Jewish culture; the Chehlom or “fortieth day” in Shia culture, etc.). The work of mourning for close friends and family develops through these two constant patterns, which come in a multitude of forms across time and space. Hertz questioned the meaning and social function of these rites for human societies. He showed how they enabled the group to counter and absorb the disorder caused by the intrusion of death into the symbolic order and the social body. Mourning is processed through a “double and painful work of disaggregation and mental syntheses” (Hertz 1928: 79). “Disaggregation” means separating members of the community from a deceased person “who is too big a part of themselves”; and “synthesis” means reintegrating the deceased in a symbolic order and a continuity. This twofold movement, processed through funerary rites, is a condition of the order and continuity of society itself in the face of death.

By dislocating these rites, the treatment of the opponents’ dead bodies attack at a sensitive pivot, where affects, symbolic representations, and the social order develop. The violence deployed on executed prisoners reverberates in concentric circles or produces new effects of constraint and control over the surviving close family and friends, as well as wider (militant, neighbourhood) social networks. This is how the living are governed through the dead – their dead.

Silence: sealing the borders of collective belonging

Interestingly, the stories that introduced this untold, alternative history of post revolution Iran have done it in foreign languages and in other countries. Dowlatabadi’s novel is still waiting for an official authorization at the Ministry of Guidance. The author made it clear more than once that the book would be published in Persian inside Iran, or just remain unpublished: this dissonant voice on the past should be heard from within the Iranian society. By making his request at the Ministry of Guidance public and by mediatizing it, Dowlatabadi is using the veins of literary prestige and moral authority to challenge univocal, instituted discourses and policies of the past.

The discourse on the foundation of the Islamic Republic as a success story and the manifestation of a popular sovereignty lay at the foundation of the national identity constructed after 1979. Since more than 70% of the Iranian population were born after this date and relate to this past only through second hand accounts and history books, reopening the post revolution years of extreme violence and terror bears a high stake in the present.

Aziz’s Notebook has taken a different publishing path: first published in French and English, it has been published in Persian through a publishing house in exile. It is thus not yet available to the Iranian public either. Although first published in translated versions, these two stories were originally written in Persian and inside Iran, at the time of the events. As for The House of the Mosque, which does not exist in Persian, it was directly written in Dutch by an author who has learned this language at the age of 33, and has chosen to speak directly from the hearth of his exilic condition. These linguistic detours and uneasy publishing trajectories offer us stories, and a piece of contemporary history, that have a hard time being told out loud in their own language: a noteworthy feature that shows us how silence and denial have engineered the boundaries of national identity and collective belonging. A collective memory of violence may be hard to build because silence, in the first place, is a tool through which the State reshaped the “collective”.

References

Kader Abdollah (2011). The House of the Mosque. Edinburgh, Canongate Book.

Mahmoud Dowlatabadi (2012). The Colonel, Brooklyn, Melville House.

Chowra Makaremi (2013). Aziz’s Notebook. At the Hearth of the Iranian Revolution. translated by Renuka Georges. Delhi, Yoda Press.

Michel Foucault (2001). Dits et écrits. II, 1976-1988. Paris, Quarto Gallimard.

Robert Hertz (1970 (1928)). Sociologie religeuse et folklore Paris, Presses Universitaires de France.

Michael Taussig (1999). Defacement: : Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford, Stanford University Press.