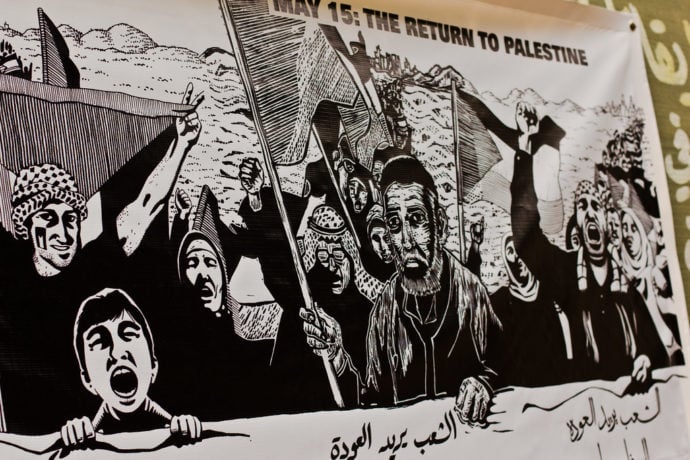

There has never been a better documented war than the one unfolding in Palestine at the moment. As Elshaik, Martinez and Shaer write in their contribution to Allegra’s Framing Gaza thread:

“Daily, images, videos and voice notes proliferate faster than they can be witnessed or heard or known. We have numbers, data visualizations, graphs and charts of death tolls and aid trucks and calorie counts. […] And of course, [we have] human rights violation reports, health analyses, compendiums of laws. We have transcripts of government officials calling for Gaza to be flattened, leveled, made uninhabitable.”

The facts of war can no longer be disputed. Instead, what is at stake is how violence and harm are framed: how certain kinds of violence are made visible, and others invisibilised, and how certain forms of suffering become illegitimate. We must resist this selectivity, or ‘willed blindness’, as Lila Abu Lughod put it.

When our own colleagues start censoring themselves for fear of being sanctioned, we may want to ask: what is scholarship good for?

In the dominant framing, most Western governments have unquestioningly endorsed Israel’s right to self-defence as an absolute, however tenuous that might look from an international law perspective. When even a mention of economic sanctions becomes a legally punishable offence (such as it is the case in Germany), when any call for, in a first step, simply a halt to the indiscriminate killing of civilians by state armed forces is equated with Antisemitism, governments and societies in Europe lose any claim to being the supposed guardians of an international rights-based order.

Rather than trying to actively help find solutions to the current conflict that is claiming thousands of civilian lives, the debates in many parts of Europe have been chiefly about who said what, and what kinds of questions and political opinions are deemed verboten. As a consequence, the space for debate and for expressing solidarity with Palestinians has considerably shrunk, alarmingly also at universities where we would expect vigorous and nuanced discussion to be possible and welcomed. Instead, many universities have lent themselves to staging McCarthyesque spectacles of denunciations, ritual self-flagellations and dismissals. When our own colleagues start censoring themselves for fear of being sanctioned, we may want to ask: what is scholarship good for?

Allegra was created to be more than just another anthropology publication. We want to foster a sense of community, mutual support and engaged scholarship that the neoliberal university has gradually destroyed. Our editorial collective is less concerned with demands for conceptual and theoretical ‘newness’ and anthropological ‘turns’ than with making the world safe for human difference. We are defending a vision of anthropology that is ‘in the world’, i.e a ‘worldly’ anthropology, that produces theories that can be used as stones. In that spirit, we seek to amplify voices that often remain marginalised, particularly voices that talk to experiences of violence and the legacies of colonialism, and to recentre a postcolonial framing that despite calls to decolonise our universities still remains marginal or wilfully misinterpreted.

We felt that an open thread would provide space for immediacy and for these voices to be read.

We know, from people who have told us informally, from comments when discussing other matters, and from authors who have withdrawn pieces from Allegra in the middle of the review process, that we’ve not made everyone happy. And, of course, we understand. We understand that given the heaviness of history in certain parts of Europe, and the structures that seek to repress those certain views, not everyone feels comfortable or safe publishing on a site that includes pieces that frame Palestine-Israeli relations in terms of settler colonialism, apartheid and genocide. Yet we fully assume our killjoy status, to use feminist scholar Sara Ahmed’s expression, because we believe that the purpose of critical scholarship is primarily to challenge the status quo.

We felt that an open thread would provide space for immediacy and for these voices to be read. The authors we published in our Framing Gaza thread are scholars of the Middle East, or decolonial scholars who mobilise their knowledge of postcolonialism to offer analyses of the current conflict that unpack and disrupt the dominant frame.

Unpacking and disrupting the dominant frame also means that we should ask questions about how the institutions to which we belong are complicit in perpetuating the occupation of Palestinian territories. As many Israeli and Palestinian anthropologists themselves have highlighted, the inclusion of Israeli academic institutions in European funding mechanisms contributes directly to the ongoing repression of Palestinians. There is ample evidence that in Israel, academic disciplines from technology to the social sciences are implicated in the occupation. Now that there is no single functioning university left in Gaza, it is surely the moment for such reflection and collective action.

Just like trade union work within our institutions is important to address issues relating to labour, we can think about what our departments, institutions and wider networks can do in response to the latest surge of violence in Palestine. In this regard, we can build on past examples of solidarity within academia. Conflicts and repression in Myanmar, Ukraine and Turkey led universities to open up scholarships and places to scholars and students alike whose work or study was interrupted or academic freedom curtailed. As South Africans know from their own experience, liberation and higher levels of equality come rarely from internal resistance alone and are dependent on complex interplays with external forms of pressure.