“How can we ever forgive them?” I find myself asking over the past month and a half. I do not raise the possibility of forgiveness to suggest a moral high ground nor to dictate ethical conduct for the victims of genocide. Indeed, to talk about forgiveness in a time of televised genocide may just as well be talking about the impossibility of forgiveness. Yet, the topic has already been raised, if surreptitiously. Judith Butler, in a widely shared essay in the London Review of Books published on October 19[1] (and since translated into Arabic[2]) asks Palestinians and Israelis to imagine a future in which all parties “live together in freedom, non-violence, equality and justice,” and for the world to accommodate this difficult task by producing a generation of “dreamers” and the like. It is true that Butler prefaces this rosy vision of the future by acknowledging decades of Palestinian suffering under Israeli occupation, albeit this acknowledgement is itself prefaced by her proclaiming any possible justification for Hamas’s uprising on October 7 as “corrupt moral reasoning.” It is also true that Judith Butler has engaged with Palestine for too long to slight her as a mere spectator-pundit; the kind of detached political commentator that has thrived on talk shows and tweets since October 7. No, Butler, apart from being a groundbreaking theorist of gender and politics, has genuine Palestine credentials. She has written a book on Jewish critiques of Zionism,[3] she has lended her name to countless letters in support of boycotts against Israel and legal appeals in support of troubled Palestinian scholars, she has given visiting lectures at Birzeit University near Ramallah, and in 2006 she made the brave (but, in the West, unacceptable) observation that Hamas belongs to the Global Left; a comment that she later retracted. There can be no doubt that Butler means well. But by asking Palestinians to somehow ignore a near-century of oppression in service of a still-hazy just future, and asking Israelis, in turn, to absolve the “corrupt moral reasoning” of Palestinians, she employs a kind of moral philosophy that asks the victims of violence to share the burden of responsibility with the perpetrators of the same violence, and vice versa. In very unphilosophical terms, she asks everyone to put their differences aside and just move on.

There is a genealogy to such thinking. In a stunning section of her magnum opus The Human Condition,[4] Hannah Arendt outlines two ways of navigating predicaments one encounters in the world; those which she calls “faculties” of human action. One is by punishment and retribution, a kind of action best exemplified by the vengeful God of Last Judgment. The second is forgiveness, which, according to Arendt, was first “discovered” by Jesus of Nazareth in his dying moments on the cross. Jesus’s discovery is radical, writes Arendt, because in the Judaeo-Hellenic context of 1st-century Palestine, it was understood that the power to forgive belongs only to God. By bringing this divine power to the realm of human affairs, Jesus made way for political possibility previously unavailable to mere mortals. Forgiveness, thus, is radical politics.

In very unphilosophical terms, Butler asks everyone to put their differences aside and just move on.

But Arendt herself was a mere mortal, and, thus, inconsistent. She saw Jesus’s discovery of forgiveness as the “miracle that saves the world,” but she was herself unable to forgive. It is often ignored that despite her well-known verdict of Nazi evil being ultimately “banal,” Arendt also concurred with the court’s verdict that Adolf Eichmann should be put to death.[5] Butler, writing about Arendt’s perplexing lines of thought on the matter, offers the following analysis: “No one dies as a consequence of Arendt’s judgment and words, and yet perhaps they show us less the reason for the death penalty than its conflicted and theatrical vacillation between vengeance and some other version of justice.”[6]

What might forgiveness as another version of justice look like? In a (relatively) recent book that has all the complexities and contradictions worthy of a classic, Mahmood Mamdani explores two models of possible aftermaths of political catastrophe.[7] The first is the denazification process taken by postwar Germany, and the second is the end of apartheid in South Africa. An even cursory look at this typology shows that it is almost analogous to Arendt’s two faculties of human action (I say almost and not exactly, for reasons to be explained later): retribution, on the one hand, and forgiveness on the other. Denazification entailed the ethnic cleansing of 12 million Germans from Central and Eastern Europe into the two postwar Germanies, show trials of SS officials in Nuremberg, and a peculiar self-flagellation at the level of national identity that continues to persist in the modern German state; particularly in its unqualified support for the welfare of the world’s Jews for which Germany sees Israel as the indisputable guarantor. There is also the millions of Deutschmarks paid in reparations to families of victims of the Holocaust, the total subjugation of West German manufacturing and military interests to the United States in the immediate postwar period, and periodic celebrations marking the anniversary of its own surrender to the Allied forces, now understood to be Germany’s liberation from itself. In denazification, there is a clear perpetrator—Germans—and a clear victim—Jews.

Although Mamdani does not use the term, it is forgiveness that characterizes his second model, that best exemplified by South Africa. For Mamdani, post-apartheid South Africa collapses identities of perpetrator and victim into a broader category of “survivors;” survivors meaning those who together “witnessed” a protracted moral and political South African nightmare, and together survived it. Features of this model include the establishment of institutions like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in which both colonizer and colonized work together towards new political frontiers, no retribution against the perpetrators of violence (in fact, the category of perpetrator does not exist), and other such concessions. Mamdani makes clear that it is this model that is the only viable way forward for Palestine: a “non-national” state that is not exactly a binationalism of Jewish/Arab democracy but, rather, an anonymous political project that is a homeland for all, and without identitarian national markers. He writes: “The Palestinian moment will arrive when enough Israeli Jews are confident that they will be counted among Zionism’s survivors.” In this, Mamdani’s vision is in agreement with Butler’s call for “dreamers.”

Watching now the carpet bombings of entire neighborhoods, the bravado military conquests of hospitals, the psychological humiliation of evacuees, the denial of basic amenities and nourishment to over two million people, the repeated propaganda lies and fake news, the arrogant lauding of genocide by elected officials, the Abu Ghraib-style abuse of political prisoners, the extrajudicial killings in the West Bank, and more (the list is by no means exhaustive), one wonders how anyone can take Mamdani’s survivor model seriously. Is the hindrance to a just future in Palestine really in the hands of Israeli Jews who are as yet unconvinced whether or not to take the leap of faith to “survive” Zionism? And can the political solution that was devised to end South African apartheid really be viable in a Palestine ravaged by psychotic Israeli hellfire? It should be mentioned here that the anonymous category of “survivor” was first coined by Wynand Malan, the Afrikaner member of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It could not have been otherwise. Mamdani mentions this curiosity, but does not give it any importance.

Can the political solution that was devised to end South African apartheid really be viable in a Palestine ravaged by psychotic Israeli hellfire?

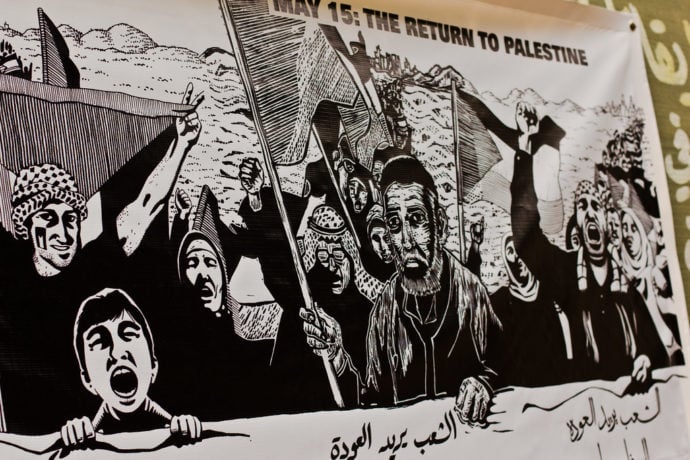

The wider problem here is the discursive limits regarding what kinds of futures and political projects are welcomed by a community of scholars that would of course prefer a reprieve from endless cycles of violence. Mamdani is an established scholar, the kind who is able to get away with sweeping moral reasoning in parts of the world where he might not have a libidinal stake in the game. Even in less agitating times, I was struck by Mamdani’s argument from an earlier book that Darfur was perhaps not a genuine genocide, whereas Rwanda was.[8] The point is not whether Mamdani is correct or incorrect, but that the matter of genocide, especially keeping in mind that the reader might also be the victim, requires a certain sensitivity, a certain humility and tact. Mamdani is astute in noting that political realities in Israel/Palestine are never static, and he observes shifts in Israeli political trends over the past century and a half that inform his prescribing the survivor model. But Mamdani seems ignorant of shifting Palestinian trends also. The binationalism once favored by many Palestinian activists, and critiqued by Mamdani, has over the past decade transformed not into a survivor paradigm but into an Algerian model of revolutionary decolonization; one in which there is no future for the colonizer, less so as a survivor. This is an understandable development, regardless of moral judgment, and especially for younger generations of Palestinians who have never known, or are too young to remember, anything but the misery of the current status quo. One indication of this development is the shift in terminology. In the spirit of Confucius’s famous dictum that “the beginning of wisdom is the ability to call things by their right names,” the new activists refer to all Israelis as “settlers” and all Israeli localities, from those in the West Bank hilltops to Tel Aviv, as “settlements.” The new activists are also highly literate in the pedagogy of the oppressed, well-read in Fanon and Kanafani, and they know that the currently televised genocide is not event but structure, with each and every one of its components already practiced for decades; only that it is has now escalated to a scale previously unseen, and that the world is now again looking.

The new activists are also highly literate in the pedagogy of the oppressed, well-read in Fanon and Kanafani, and they know that the currently televised genocide is not event but structure.

I do not think that Palestine is Algeria, nor that the Jewish relationship to Palestine is exactly symmetrical to the French relationship to Algeria. In some ways, France was a more benevolent colonizer than Israel can ever be, eventually granting French citizenship to all Algerians and stealthily adopting Algerian decolonization into its own Hegelian self-image of liberté-égalité-fraternité.[9] This is not to say that the French colonization project in North Africa was anything but brutal. It was brutal, entailing massacre after massacre that have left permanent psycho-social scars. But these are the standards to which Israel has lowered itself. In other ways, Israelis do not have a metropole to which to flee like the French pieds-noirs did, should Zionism be violently overthrown. The point, however, is that if one feels the Palestinian tragedy authentically in one’s bones, as any serious scholar writing about Palestine should, then it is imperative to be empathetic to these intricacies and nuances of political futures that reflect the reality of the Palestinian experience. Lecturing to Palestinians about corrupt moral reasoning, in its various forms, is the antithesis to such empathy.

“How can we ever forgive them?” I still find myself asking. In my more sober moments, I know that forgiveness is inevitable. I do not mean here forgiveness as radical politics, as per Arendt, nor as political concession. Rather, forgiveness is an unavoidable reality of everyday life, of encountering the face of the Other, of not responding to genocide with counter-genocide. Forgiveness of this kind is difficult and constant work. Palestinian activists may very well discover in the end that forgiveness is the pragmatic political solution, even the moral one, but this is something that has to be discovered through experimentation—as Jesus did—and not prescribed by top-down moral reasoning. Jacques Derrida once wrote that only the unforgivable is truly forgivable, for otherwise it would not be a thing worthy of forgiveness.[10] He also frowned upon “transactional” impetuses towards forgiveness that rely on the logic of economic exchange, as Mamdani’s survivor model does. It is because of this that I distinguish Butler from Mamdani, and Arendt from both. Arendt’s call for forgiveness is not a call to move on. Rather, it is a call for a revolution of consciousness, and her own inability to forgive Eichmann shows a vulnerability and struggle-of-the-self that touches my heart.

Arendt’s call for forgiveness is not a call to move on. Rather, it is a call for a revolution of consciousness.

But here there are intrigues. I return now to the image of Jesus on the cross, that which Arendt locates as the site of the discovery of forgiveness as human action. Luke 23:46 is the biblical verse generally considered to be the climax of Jesus’s mission. By this point in the Passion narrative, Jesus has already forgiven his executioners, and a solar eclipse is passing over Jerusalem, bringing darkness over the earth. Jesus, with his last gasps of breath, entrusts his spirit to the custodianship of God. He then dies on the cross: “Jesus called out with a loud voice, ‘Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.’ When he had said this, he breathed his last.”

In Arabic translations of the Gospels, probably some of their earliest translations ever made, at least orally, the action of his death (the Greek exepneusen) is translated as aslam—meaning “I submit” or “I surrender;” essentially the same form that six centuries later gives Islam its name. If forgiveness is radical politics, or if one must one way or another be compelled or obliged to forgive, take this language game as a warning against confusing this politics with surrender. Take care also to consider the awesomeness of what resurrects when a movement is violently extinguished.

References:

[1] Butler, Judith. 2023. “The Compass of Mourning.” London Review of Books 45(20): https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n20/judith-butler/the-compass-of-mourning.

[2] https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/45447/بوصلة-الحداد

[3] Butler, Judith. 2012. Parting Ways: Jewishness and the Critique of Zionism. New York: Columbia University Press.

[4] Arendt, Hannah. 1958. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[5] Arendt, Hannah. 1963. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Viking Press.

[6] Butler, Judith. 2011. “Hannah Arendt’s Death Sentences.” Comparative Literature Studies 48(3): 280-295.

[7] Mamdani, Mahmood. 2020. Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

[8] Mamdani, Mahmood. 2009. Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror. New York: Pantheon Books.

[9] See: Shepard, Todd. 2008. The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

[10] Derrida, Jacques. 2011. On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness. London: Routledge.