“Tuesday

8:30 – Good morning circle

9:00 – I’m raising the children

you have forgotten.

10:15 – And you have no

goddamned clue.

11:05 – Lunch

12:10 – Just. Pay. Me. Pay me.

12:55 – I refuse to fold my hands.

1:40 – Would you love them

as your own? As I do?

2:30 – Dismissal”

(Ewing 2017, 83).

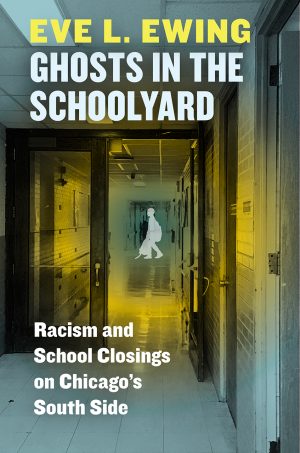

The above epigraph comes from Ewing’s Electric Arches, where she condenses the life of a teacher in a system that limits the value of education, and seeks to see education as simply a mechanism for industry with limited impact on children and society writ large. Ghosts in the Schoolyard, like Ewing’s poetry, is not an academic treatise, but “a story that is revelatory based on the experiences of my own life and the lives of community members living in the shadow of history” (7). Born and raised in Chicago, Ewing is a sociologist of education and writer. She is a graduate of Harvard University and is currently an Assistant Professor at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration. Their work focuses on social structures such as racism and social inequality.

It is a testimony, acting as witness (174) to the blatant and unabashed racist and wanton destruction of African American communities in Chicago.

This book is exactly that: an account of community in the historically African American neighbourhood of Bronzeville on the South Side of Chicago; and is a well-wrought analysis of educational policies, the impact these have on the students & teachers, and the ways that community groups sought to fight back against the Chicago Public School (CPS) decisions and narratives to preserve the educational futures of their children. The book refuses and refutes suggestions that these two components are separable.

Ghosts in the Schoolyard takes as its locus the 2013 closings of Chicago Public Schools. The original target was to close as many as 330 schools of which 90 percent “were majority black, and 71 percent had mostly black teachers” (5). These closures were billed by CPS and the city as necessary due to the schools being underutilized and underresourced. Based on Chicago’s racist and economic segregation practices, the reality for these students was that “…students leaving a school facing challenges are likely to end up in an equally challenged school close by” (9). These closures are, as Ewing illustrates, part of a broader-system of historical (and current) processes and structures which dictate and perpetuate racist and oppressive regimes; while, at the same time, demonstrating the ways that these communities fight for justice and seek to maintain the history and richness they have built. Throughout, what is clear is that “losing a school is losing a piece of a history, a piece of self-understanding and personal narrative” (145); and that it is impossible to separate these closures from broader forms of harm and violence.

In examining the school closures, Ewing deftly addresses the structural problems while maintaining the voices of those impacted by these issues.

Throughout the process of hearings regarding the school closures, the narrative of Chicago Public Schools was that they were simply ‘failing’ and that by closing these schools students would, in the end, get a better education. By the end of the 2012-2013 school year they ended up closing 49 of these schools. An astounding 42 percent of displaced students ended up in the lowest-ranked schools. These closures were a part of a wider set of policies designed as part of the “expansion of ‘choice’ within CPS” (23), where this ‘choice’ was unevenly distributed by neighbourhood, race, and economic status. While CPS framed the community as driving the process and hearings, for Ewing, as she lays out thoroughly, Chicago Public Schools had predetermined the outcome long before the discussion began.

Expanding out from the 2013 school closures, Ewing situates them in the context of housing projects and segregation in Chicago’s South Side neighbourhood of Bronzeville. By 1970 nearly half of Bronzeville residents were living in housing projects (73), with the majority of residents under the age of 18.

Tying these pieces together, Ewing notes that ‘Segregation, restrictive covenants, Willis Wagons, demolition of public housing – these policies all laid the groundwork for the present reality of empty schools dotting the landscape’ (90).

There is, then, a demand for historical analysis and recognition; to view the recent school closures as isolated is, itself, a form of violence that denies and seeks to dismiss the racist history of Chicago, the Chicago Housing Authority, and Chicago Public Schools. Ewing notes, we “see a system that fails to take responsibility for creating the conditions of that social instability, preferring to act as though it’s all a matter of individuals’ pulling themselves up by their bootstraps and teachers’ needing to work harder” (123).

Ewing’s refusal to forgo structures for people, or people for structures, is what makes this book incendiary.

The systems of racism and neoliberalism are hellbent on pushing individuals to compete against each other, with the end goal of leaving the systems untouched. Through this, Ghosts in the Schoolyard is able to theorize ‘institutional mourning – the idea that we can mourn lost institutions just as we mourn lost people’ (14).

Ewing writes, ‘death that results from extreme violence, especially state violence, can feel anything but natural’ (142). These deaths are not just of people, but of institutions, communities, dreams, and possibilities. Throughout the book she brilliantly makes the case that schools are an integral part of a community, and that their destruction constitutes an attack on the people through indirect means.

Activists in Chicago organized in March 2019 calling for more funding for schools, not more police (photo by Charles Edward Miller, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In preparing to teach my class on neoliberalism this semester, I scribbled on one of the assigned readings: “Are you upset yet?” This book is upsetting. It documents the racist, classist, and oppressive structures and people that are tearing communities apart; and the ways that school children are taught this through the lived realities of disempowerment, diminishment, and deprioritization. While all that is true, the communities on the South Side of Chicago are still there, “despite all attempts to eradicate us” (154), and they are still fighting for their right to self-determination and education. In his A People’s History of Chicago, Kevin Coval annunciates the ways that Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Chicago need to redress the injustices they have fashioned. In amongst a wide litany of atonements, they must:

“atone for the smug assuredness

atone for the maintenance of two cities

stratified & unrecognizable to the other

atone for the bounty of the north side

the scarcity of the south

the want of the west

atone for the erasure of the public

school, space, housing, parking” (Coval 2017, 118).

Ewing’s masterful book delivers a clear message: that people’s well-being is contingent on everyone in the community: “If I am because you are, it follows that my understanding of myself is bound up to my relation to you and my place within our network of relationships” (131). At its core, while Ewing documents racists practices and their impacts, she shines light most heavily on the ways in which communities rebute and refuse them.

This trajectory is continued in Ewing’s forthcoming book 1919 , an exploration of the race riot that happened in the year 1919 in Chicago. She elegantly and powerfully continues to voice the interconnections between individuals, institutions, and the force of history. From the poem this is a map:

“this is a map of my body

this is the blood of my rivers

this is the bruise of my marshland

this is the sinew of my furthest ridge, and

this is a map of the railroad.

and if I could stand and walk I could make it all the way back

to my granny, pinching snuff and humming

and if she looked up she would say boy, my baby,

where you been all this time.”

(Ewing 2019, p44).

References:

Ewing, Eve. 2018. Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018

Ewing, Eve. 2017. Electric Arches. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Ewing, Eve. 2019. 1919. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Coval, Kevin. 2017. A People’s History of Chicago. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Featured image by Feliphe Schiarolli on Unsplash