Part Four: “When will this Covid be over?”

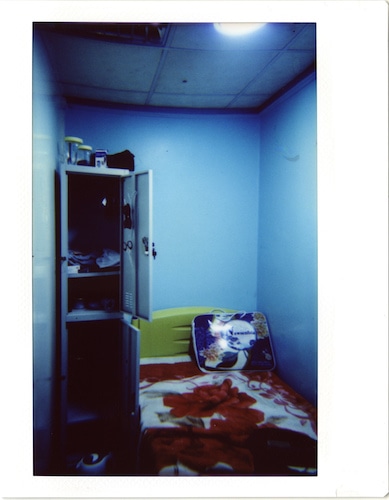

During the first month of T.’s search for work in Dubai, Covid-19 felt like something that had happened last spring. We might have quite forgotten about it, were it not for the obligatory masks and the ongoing shortage of airport jobs. Dubai had chosen to stay open, protected by a discipline of masks and social distancing. However, the discipline was comparatively loose. Cafés, restaurants, bars and shops have remained open (except for those that went bankrupt during or after the lockdown, and there are frighteningly many of them). Most people live in shared accommodations where they interact at close proximity. In the dormitory I lived in, and in others I visited, social distancing is impossible. Eight men shared a room – and this was a spacious arrangement; the room was large and might have easily been made to accommodate 15, even 20. Eating shared meals from shared plates was a daily emotional highlight that we were unwilling to give up. In the Dubai metro, which is the city’s fastest and very efficient means of public transportation, only half of the seats are in use to maintain distance among passengers, but passengers stand shoulder to shoulder in full rush hour-trains. This invited some to comment jokingly that you can only get Covid while seated, but not while standing.

In the dormitory I lived in, and in others I visited, social distancing is impossible.

And yet, Dubai’s attempt to maintain the impression of itself as an island of normality with the situation well under control was successful, because it was something that most people in the city desired as well. They urgently wanted and needed business as usual. Just before New Year, the infection numbers, which had remained miraculously stable for almost two months, suddenly jumped and kept rising fast. By the second half of January, it became increasingly clear that Dubai’s strategy to stay open by means of masks and distancing was resulting in an increasingly uncontrollable outbreak of the pandemic.

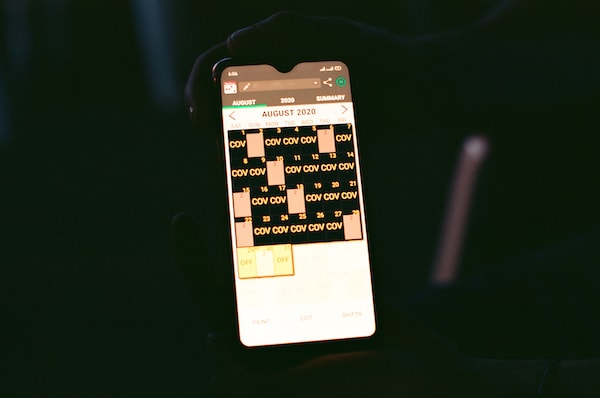

One day in late January, T., his former colleague W., and I went to an open interview for a data entry job at a private hospital. Although T. had a new job, he didn’t feel secure in it. He was still on a trial period, and the company could still sack him from one day to another. Thus, he decided to keep looking for alternatives until the end of his trial period. Arriving on the bus from Ajman where we had spent the weekend, T. went to his accommodation in the Deira neighbourhood of Dubai to change into his suit for the interview, and returned with dramatic news. One of his roommates had tested positive for Covid (at his work, he was required to test regularly). The infected roommate was alone in his room, and the five other inhabitants of the room didn’t know where to spend the night, fearing that they might get quarantined as well.

His landlady tried to convince him that he shouldn’t worry since “Dubai is full of Covid anyway.

On the previous evening, we had received a phone call from H., the cousin who had picked up T. at the airport upon his arrival. He had just tested positive. He had a secure job, good income, and a spacious apartment that allowed him to go to a test when he felt sick, and stay in a room by himself for the time of the quarantine – resources which many others in Dubai lack. “Just yesterday, I was wondering what happens if somebody in a shared accommodation gets Covid, and now it happens!” said T. Luckily a friend offered him temporarily accommodation for a few nights, and he managed to get some of his personal belongings from his accommodation, while his landlady tried to convince him that he shouldn’t worry since “Dubai is full of Covid anyway.”

In the dramatic and anxious mood evoked by this turn of events, we arrived at the private hospital that looked to be of high quality. There, an HR employee outlined to us the job offer: data entry for Covid vaccinations, part-time: 3 x 12 hours a week, 2500 dirhams with visa but without accommodation, with transport from the main hospital to the worksite in a remote suburb. They looked for employees who could start immediately. “Immediately?” we asked. “Yes, tomorrow.” The HR employee reminded us that it was a good offer because lots of people were looking for work, and the Covid situation was getting rapidly worse. He also stated that if they proved themselves in the job, it might be a way to get other, better paid jobs in the hospital. T. and W. decided against it – T., because his current job was better, and W. because he was hopeful of finding something more long-term: “I’m a married man, I can’t afford adventures.” Later, while we were drinking karak – a South Asian-style tea with milk and spices, very cheap and popular in the Gulf region – at a tea-stall, T. reminded him that waiting for a better offer is just as adventurous as taking a temporary job.

Just two days later, two of T.’s colleagues at work were quarantined at their homes after they, too, had tested positive. He began to fear a new lockdown, and his main concern became getting his new contract and residence permit as soon as possible to be at least a little bit on the safe side.

Dubai’s bet, and a bet it is, has been that it will be able to vaccinate enough of its population before the pandemic gets out of hand.

Around the same time with these events, international media began addressing the rising number of infections in Dubai. They addressed mainly the luxury side of the pandemic: Western tourists having a good time in the beach resorts, bars, and nightclubs. In this way, they reproduced Dubai’s own public image as a fashionable city of luxury and pleasure. Dubai reacted with increased restrictions in tourist and leisure sites: higher distances between tables in restaurants, and a ban on live entertainment in bars and restaurants. Such measures could be taken without causing a second economic standstill that Dubai’s volatile economy might not survive. But how to provide distancing in accommodations in a city where shared rooms and apartments are the standard? During the time that I lived in the shared room in Ajman with 7 to 8 other men, only two persons (me among them) took a Covid test, and we took it to enter Abu Dhabi (which due to its oil wealth can afford a more restrictive Covid-19 regime than Dubai). Several inhabitants developed a cold during January, and one also lost his sense of smell and taste for two days; but nobody would get tested, because they were too afraid of the consequences of a positive test that would interrupt their search for work, and even make them lose their income or accommodation. How to motivate migrant workers to test and self-isolate under such conditions?

Dubai’s bet, and a bet it is, has been that it will be able to vaccinate enough of its population before the pandemic gets out of hand. The UAE aims to vaccinate more than half of its population by March. To accomplish this, they have opted for the easily available and storable Sinopharm vaccine, while the Phizer-BionTech vaccine is so far only available for healthcare workers and senior persons. The UAE has invested heavily in the Sinopharm vaccine, which was also tested here. Data from Sinopharm tests has not yet been made public, which is why it is not possible to know whether the up to 86% protection it is claimed to have is true. I definitely hope it is, because during the last week of January, the situation was clearly getting out of hand. And yet nobody in my accommodation went to receive a vaccination due to a widespread scepticism towards vaccination. (This is likely changing, though, as employers are increasingly requiring their workers to take a vaccination.)

Paradoxically, however, Dubai may be partly protected through pockets of herd immunity that seem to have emerged largely unnoticed among workers. Because workers are mostly young and healthy (a medical test is a precondition for work visas, and retired migrants can seldom afford to stay), fewer people die or develop severe symptoms than elsewhere. An entire floor in an apartment block can get sick without the authorities noticing, as long as nobody takes a test or needs to be hospitalised. In the company where T. worked before the lockdown, almost everybody in the company labour camp got sick with Covid-like symptoms in March. In the shared room I lived in, five of the eight inhabitants probably had Covid during the autumn, three of them when everybody in the apartment got sick in October, and two (including myself) before their arrival here.

If Dubai could afford a new lockdown, one would probably be in place now. But it cannot afford it, and neither can the workers and jobseekers I have met here. They agree, and I agree with them, that a new lockdown would likely be even worse than the current situation. It would hit hardest those who already have the most to lose: workers who urgently need to keep their jobs, and jobseekers struggling to find work in the middle of a crisis – work without which their families have no income and their children can’t complete their schooling.

Uncertainty about the when of lockdowns, openings, and prospective economic recovery is perhaps the greatest cause of stress among the jobseekers I met.

My roommates were interested to know what I would write about my encounter with them, and on one of my last evenings in Ajman, four of them gathered with me in the room, and I presented to them an improvised Arabic translation of a first draft of this essay. They gave me good and useful feedback, and then we decided to take a walk. We strolled around the streets of a recently built neighbourhood, stopping twice to drink karak at a tea stand, talking about plans for the future, housing expenses, driver’s licences and parking lots, dreams and emotions, and much more. Our mood was good and relaxed. At the second tea stand, F. suddenly turned to me and said: “Doc, I have a question. When will this Covid be over?” D. overheard his question and commented: “Everybody here asks the same question.”

Uncertainty about the when of lockdowns, openings, and prospective economic recovery is perhaps the greatest cause of stress among the jobseekers I met. To endure a lack of income for a while is one thing; to pay for a plane ticket and to spend money on living and moving around in an expensive city without knowing whether and when it might pay back, means that every step that one takes might turn out to be the wrong one, and yet not taking it is just as risky.

With a salary forthcoming, it becomes easier to be flexible. T.’s new job was paid well enough that it provided him some flexibility. One week after he left his accommodation where the infected roommate was still staying (he had nowhere else to go), T. was offered a partition (just large enough for a bed and one’s bags, partitions are individual spaces divided from a larger room) for 1100 dirhams per month. It cost more than twice the rent of his bed in the shared room, which meant that he would be able to send very little or even no money home that month. However, he accepted it because it provided him safety from the likely risk that more of his roommates might be tested positive and quarantined, which was likely to happen again in either his current or other shared dormitories.

In the beginning of his return to Dubai, T. had tried to find something long-term and certain, and had been stressed to his limits about uncertain choices. Now, he could look forward again in a more hopeful mood. For the first time since his arrival, he told me more about the house he was building, and a terrace for summertime leisure gatherings that he hoped to add on its roof. One day, when I met him after work where he was now feeling more confident as he was quickly learning how the system worked, he told me that every migration costs money at first before it brings profit: it’s been so every time, and with this one, he’s given himself until the end of this year. Only by then does he expect to be saving at the scale that he needs to finish building his house and provide for his daughter’s education. But this makes his plan of return in two years rather unlikely.

This essay could be concluded with more sophisticated anthropological theoretical reflection about the temporality of neoliberalism, growth and crisis, but now is not the time for it.

All images are owned by the author