Hillbrow, Johannesburg: It’s April 2008. I am in the lobby of the Ambassador Hotel, one of Johannesburg’s most happening nightclubs since the Apartheid era. As with the Hillbrow neighbourhood generally, the racial and national makeup of the club is quite different than it was a few decades back. With the removal of the pass laws in 1986, which ended legal prohibitions on “non-whites” residing in Hillbrow and other downtown areas, white South Africans fled to suburbs in the north of the city and a poor, largely immigrant population from across Africa and beyond took their place. The City of Johannesburg has largely neglected this area, unlike the pristine northern suburbs, and Hillbrow has tumbled into crime and poverty.

The Ambassador is hopping. Or at least it was before the police and immigration officials barged in and forced everyone to lie down on the ground. Thankfully for me, I am not among the patrons—I am here as a nervous anthropologist researching the DHA, the South African bureaucracy responsible for immigration and identity documentation.[ii] The DHA officials among whom I have been conducting fieldwork asked me to come along with them on a police raid. If I want to understand their work, they insisted, I needed to go on a raid. After many conversations with them and my academic supervisors regarding whether I could be assured of my safety and of my ability to meet the ethical obligations of human subjects research, I agreed to go along.

I arrive at the Hillbrow SAPS station at 7:30pm, as instructed. One of my DHA contacts named Desmond[iii] pulls in shortly thereafter. I walk over to his truck and we chat while other immigration officers and police begin to congregate. The iconic Hillbrow Tower looms large over us in full night-time neon blue. A humungous, white police officer with a moustache and shaved head comes over to our group and shakes my hand with a firmness bordering on provocation. The man is Superintendent (“Sup”) van Hulsteyn. He will be leading the raid tonight. Desmond introduces me with his urban Afrikaans accent as “an American who is observing us from Wits University.” Sup van Hulsteyn scoffs.

“Oh fuck another guy from Wits. These guys are always into human rights.” I laugh nervously and Desmond reassures him, “Ach, no he’s studying—what is it you’re studying again?” “Anthropology,” I say, to which Sup van Hulsteyn replies “Oh fuck, close enough.”

Sup van Hulsteyn heads over to the SAPS garage and everyone is called inside. The officers line up in military formation. Sup van Hulsteyn, standing in front, debriefs them on the raid. First, nobody will be told the locations they will visit “because of corruption.” Second, they need to be careful, he says. Two of their fellow officers were shot earlier that day and are in serious condition in the hospital. Because of this, he says, they need to assert their authority and not show “these people” any weakness. A lot of these people talk about “human rights,” van Hulsteyn continues, but the police have the right to search anyone and any business in Hillbrow because of the Section 13-7 permit the SAPS has acquired, “so if anyone complains or tells you they have human rights, you just tell them that or refer them to me.” Van Hulsteyn clearly has a disdain for the way that “human rights” discourses can limit police authority. Strangely enough, it is a legal statute that he summons to circumvent those limits.

After he finishes speaking, he invites another police officer in front who gives a shout and stomps his foot militarily. The officers and immigration officials mimic him, turn to their right and disperse out of the garage. Everyone files into their vehicles, a convoy that stretches over an entire city block. I am to tag along with Desmond.

The first stop is not far from the station, on the corner of Edith Cavell and Pretoria Streets. Police storm into a bar and haul people out, firing rubber bullets from shotguns at people on the street to disperse them. I stay in the truck while Desmond heads out. Bystanders scurry into shops and doorways. I see a boy emerge from a corner store with a loaf of bread. He waits for a safe moment and bolts out the door down the street. People crowd onto balconies in the apartments above to watch. Large, white SAPS wagons haul people away.

The convoy drives off again, pulling onto a side street somewhere down Fife Ave, a sleepy residential area lined with trees and a restaurant at the end. The restaurant seems closed. All is very quiet. Desmond tells me that they regularly visit this spot, but that Sup van Hulsteyn must have come by earlier to notify people of the raid. “Why on earth would he do that?” I wonder out loud. With a smile of admiration, Desmond tells me that van Hulsteyn likes to keep “them” guessing. Just then, the officers are given an order to arrest a group of onlookers that has formed at the end of the block. Their offense? Loitering.

After the “loiterers” are rounded up, van Hulsteyn waves me out of the truck where I have been sitting. He wants to explain to me what he and his colleagues are “up against.” Exaggerated statistics roll off his tongue confidently: experts say there are 1.5 million people in Hillbrow, but it’s likely twice that figure. 80% of them are foreigners and 50% of them don’t have permits to be in South Africa.

I have no doubt that he believes his story, which he has clearly told himself many times before. The story’s purpose is also beyond doubt: to justify their (ab)use of state power through tropes of illegality, disorder, overpopulation, and foreignness.

The urgent population control problem he describes to me is an unmistakable legacy of Apartheid, a system that was adept at transposing xenophobia and racism onto self-evident bureaucratic concerns. And, indeed, though fewer than half of the police and immigration officials out tonight are white, everyone that I see arrested is black. It is ironic, then, that many of the immigrants who live in this neighbourhood come from countries such as Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Nigeria—countries that supported the anti-Apartheid movement by sheltering South African activists who had to flee persecution in their home country.

My head hurts. Back in the truck, we zig and zag through the dark streets toward the Ambassador Hotel.

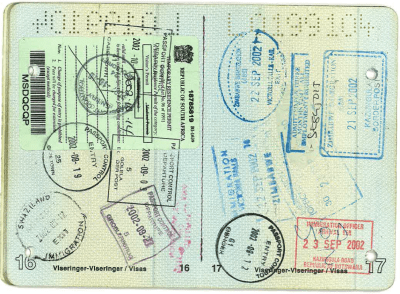

By the time Desmond and I make it into the Hotel lobby, the police have already set up a queue for “processing” the club patrons. They are mostly young men. A male and a female police officer stand at the top of the maroon carpet steps that lead from the lobby to the club, closing off the passage with a billiards cue. As the patrons file through one by one, the police check their fingerprints for criminal records on a portable biometrics scanner called the MorphoTouch. The men proceed down the steps where they are met by Immigration Officers: “Where are you from?” Non-South Africans must produce their papers or be taken to the station. Those who claim to be South African must prove it. Those from Pedi areas are interrogated by a Pedi-speaking officer; those from Venda areas go to a Venda speaker; and so on. If officers find that their accents do not sound “legitimate,” the person is asked to show identity documentation. “Let me see your papers.”

Whoosh, we are whisked away again to the days of Apartheid and passbooks.

Outside, the police are back at it, blasting rubber bullets at crowds on the street and occasionally chasing after people they find “suspicious.”

Many of the young men seem nervous – including even some of those who pass the test quickly, perhaps beset by that strange form of guilt that can capture innocent people when put under suspicion. They have very good reason to be nervous: if they cannot produce documents they will be taken to the infamously dangerous Lindela Repatriation Centre before being deported to their country of origin.

I am shocked to see police and immigration officers being so rough with the detainees, even in the presence of a conspicuous outside observer. Two Immigration Officers, whom I know to be jocular and even tender with their colleagues at the office, are shoving and slapping people. At the office the following week, one of them would approach me to say: “Do you see how it’s different out there? It’s not like in the office: you have to be rough, or else they will hurt you.”

I have described elsewhere (Hoag 2010) the logics that Home Affairs officials employ to rationalize their actions, which include a firm belief in the untrustworthiness of a racialized “public” as well as a commitment to maintaining bureaucratic “systems” that this public allegedly seeks to undermine. These logics are clearly in operation here.

A few dozen people are processed before van Hulsteyn hails me once again. He says that I “must see how these people like to have a good time,” leading me through the club where young men are lying on the ground. He curses at a few of them, violently stepping on someone’s legs for no apparent reason, and walks me through a narrow hallway. We come to a stairwell that smells of stale beer: the white-tiled stairs are littered with broken bottles and cigarette butts. Van Hulsteyn is set on showing me just how terrible this place is; how in need of discipline it is; and how detestable “these people” are. He shows me how “we found 14 of these people in here” pointing to a closet underneath the stairs. Moving down the hall further, we turn to the right, where the hallway opens up to another bar whose main entrance is on a side street. A staff member is sitting behind the bar expressionless, looking almost bored. I infer that she is a manager of some sort when van Hulsteyn tells her that she is “shut down and won’t open again.” Their operating license has expired, he explains to me.

In Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man (1987), Michael Taussig tries to account for the logics and terrors of the colonisation of Colombia, where colonists’ efforts to exterminate “savagery” led them to “become savage” themselves, perpetrating unthinkable forms of torture and murder.

Taussig finds that, for the colonist, the alterity of the colonized is nothing more than a reflection of the self: rather than exterminate savagery as was colonists’ putative aim, these Europeans reproduced it over and over; in order to expiate wildness, they found need first to conjure it in the colonized and then appropriate it.

My observations of policing in Hillbrow suggest the same paradox: “bringing order” to the violent, criminal worlds imagined by police legitimates and drives police-sponsored chaos and violence. SAPS and DHA officers conjured the chaos that justified their actions. On Hillbrow raids, this conjuring works through narratives of uncleanliness, illegality, overpopulation, and foreignness. DHA officials fabulate and fear the unknown powers of people they believe are undermining South African laws—and who therefore should not be given an inch. Draconian raids become justified and so does force. Asserting the law here entails the narrative production of illegality, as well as illegal police brutality. War is peace, chaos is order. And Hillbrow gets “cleaned up.”

Works cited

Hoag, Colin. 2010. “The Magic of the Populace: An Ethnography of Illegibility in the South African Immigration Bureaucracy.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 33(1): 6-25.

Taussig, Michael T. 1987. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

[i] This language is even used officially, as in written requests by the SAPS to the DHA for assistance with “Clean Up Operations.” [ii] Thanks to the African Centre for Migration and Society (ACMS) for supporting this research. Thanks also to the South African Department of Home Affairs for permission to conduct it. [iii] All of the names used here are pseudonyms.

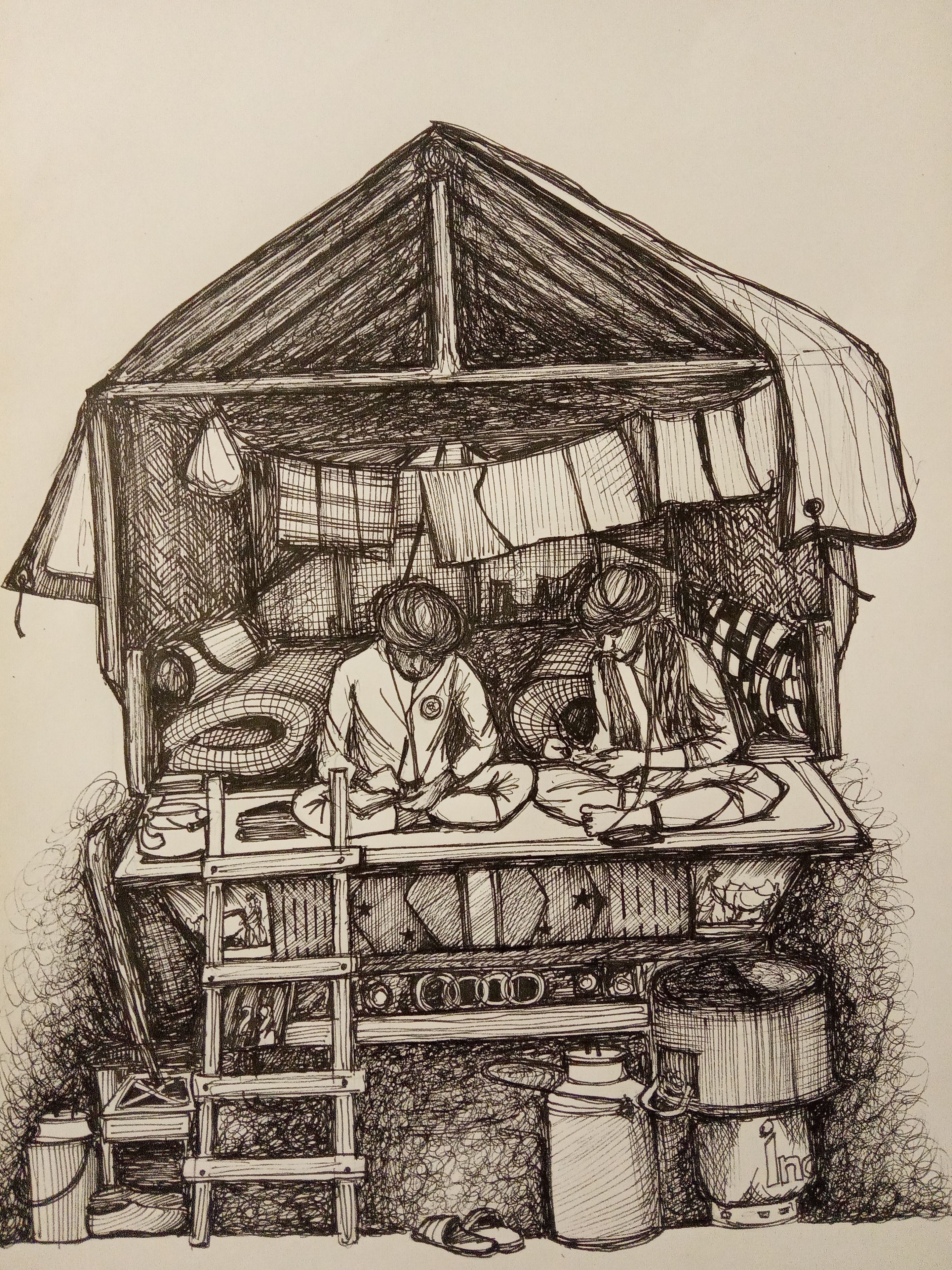

Featured image by Victor (flickr, CC BY 2.0)

This post was first published on 25 November 2014.