Based on “Fools Banished from the Kingdom: Remapping Geographies of Gang Violence between the Americas (Los Angeles and San Salvador)” by Zilberg Elana.

I had spent the last hour staring at my cell phone screen, open on the chat with Martin, my finger ready to press “send”. In my throat, a knot had formed, and each time I asked myself “what should I do with Gato?”, it pulsed. The bag of cocaine was still there on the table. The first time I tried coke was when I was fifteen years old. I was with Henri. I remember that when Gato found out, he beat the shit out of him. “Next time you make my woman try coke, I’ll shoot you in the face!”, I remember him shouting while breaking Henri’s hand with a hammer. That was not the only time Gato had beaten someone for me, but I’d be a liar if I said that, deep down, a small part of me didn’t like it. In the beginning, at least. Over time, dating Gato became more and more suffocating. First came the decision to move in together, and I still remember him dragging me out of my family house, my mum’s face in tears looking at her only daughter leaving forever. Later, Gato told me that he didn’t appreciate me spending so much time away from him and that I should’ve dropped out of school. But the worst came when I got pregnant with Marlon, and he decided that I had to stay home and take care of our son, while he was out working. During those endless days alone in our house, I started realising the nightmare he had trapped me into: it was almost as if I existed and, at the same time, I did not.

To everyone, I was known as “Gato’s woman”, some sort of appendage of him. A cook, a babysitter for his son, a trophy to show off with his friends. No other purpose or ambition. The worst was that I would have probably been okay with spending my whole life like that if he had not left for the US. However, once in L.A., Gato struggled to send money home at first, and I had to find a way to buy food. It was then that I started working in a barbershop in the neighbourhood, helping out the owner, an old man who had recently lost his daughter. He became very fond of Marlon and me and began to give me more things to do to earn a few colones more. When he died two years later, without anyone to leave the store to, he gave it to me, and I have to say it was very hard at first. But, I managed to keep it running. For the many women in Modelo who lost their husbands, the barbershop became a meeting place for them. In parallel, I also started hiring some of the girls and boys from the barrio: I like to think of the shop like those boxing gyms in movies, where the sport keeps kids away from the streets. In Modelo, everyone calls me “mama Lory”, and children beg to work with me. Most importantly, I’m not someone else’s appendage any more, but a respected part of the community, with a son that I want to raise honestly. I won’t let Gato ruin all this.

The door creaked and Gato entered the house with Marlon, interrupting my thoughts. They were laughing, imitating some cartoon character whose name I couldn’t recall. When Gato looked at the table and saw the bag, he stopped talking. I had promised myself to wait until Marlon was asleep to confront him, but an overwhelming rage began invading me, too powerful to resist.

For the many women in Modelo who lost their husbands, the barbershop became a meeting place for them. In parallel, I also started hiring some of the girls and boys from the barrio: I like to think of the shop like those boxing gyms in movies, where the sport keeps kids away from the streets.

“What the fuck is this shit?!”, I said, pointing at the bag. Gato hung up his coat and dismissively replied, “None of your business”. I felt the knot in my throat throbbing.

“How dare you bring coke in here? After all the shit this family has been through, you wanna put us all in danger? This is an MS-13 neighbourhood and you’re already on their radar”, I exploded. Gato was getting angrier at every word I said but, for some reason, I didn’t feel threatened. Maybe it was his ridiculous green mohawk or that now I also had some violent people to call, or, maybe, I had forgotten how dangerous he actually was. Whatever the case, every time he raised his voice, I raised mine louder.

“We need money, don’t we?”, he said with the most condescending tone.

“My family does not need your dirty money!”

“Your family?” blurted Gato with a scornful look, “who the fuck do you think you are? I’m the boss here, I make the decisions.”

He paused, staring at me. “You must quit the barbershop. Marlon needs his mother around…he already behaves like a fucking weirdo! I bet it’s because you’ve been around fucking half the barrio instead of raising him properly.”

The knot seemed on the verge of exploding. Hearing him shitting on all the sacrifices I made for my son when he was a gangster in L.A. was too much.

“Christ, you’d really do anything to crush my dreams. Can’t you see what you’ve become? You’re a over the hill ex-gangster with a fucking green mohawk! You’re an embarrassment to yourself. If you started dealing again you wouldn’t last five minutes! If by some miracle you didn’t die, I’d fucking kill you! I swear, I won’t let my son grow up with a marero.”

Gato jumped at me and grabbed me by the throat, in his eyes the same murderous rage as when he beat Henri all those years ago. I tried to reach for something to strike him but he pushed me to the ground. His hands kept squeezing my neck.

At that point, looking up at his tattoo-covered face, contorted in commitment to ending my life, I did something unexpected. A gesture that was surprising even to me. I stretched out my hand and, tenderly, caressed his cheek. It was a caress of pity, slightly amused contempt, one saying: “Great, Gato! This is the climax of your failed existence, killing the mother of your son.” As if he could hear the caress speak, he let go. The murderous fury vanished from his face, replaced by a mixture of terror and then surprise as he realised what he was about to do. He took Marlon in his arms, and ran out of the house into the rainy night.

It took me a couple of minutes to recover, then I grabbed the phone.

~

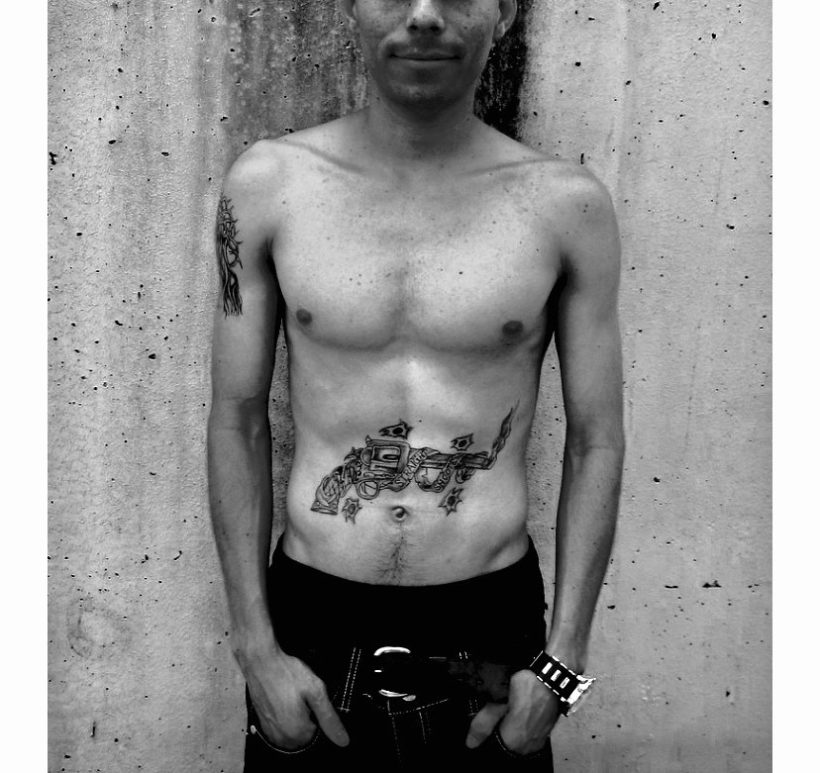

“Salvatrucha’s Tattoo 2009” by Phillip Pessar is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The car sped through the bumpy streets of Modelo. Gato had one hand on Marlon’s shoulder, trying to quell his desperate sobbing. “This bitch, how could she call me ‘marero’?”, he screamed. That he was a ‘marero’ – a gangster – is what explained the scared faces and disgusted looks he received since coming home/ A constant reminder that in Modelo, there was no space for the deported to return . There wasn’t even space even for him among the mareros any more. The MS-13 – one of the largest gangs operating in San Salvador and abroad – would’ve killed on sight an ex-member of the 18th Street Gang like him.

But his bar job in La Luna, with its low-ass wage, the shame of being back in the barrio, and the constant fear of getting murdered were not what really bothered him. It was more than that.

He left to the US as a breadwinner embracing a dangerous destiny to provide for his family. He came home a deportee, as a “fool expelled from the kingdom”, as Elana Zilberg, his academic friend, used to say. Seeing Lorena running her store successfully had been the last straw. She, who had always been “Gato’s woman” to everyone, was now bringing the money home.

Hence the bag of coke on the table. His decision to look up an old contact and start dealing again. The desire to get back into business, and regain the respect he lost. Not money, power, or the thrill of la vida loca, but respect. The respect that comes with being a gangster, someone who is seen with a mixture of fear and admiration. Someone who fucks life, not someone who gets fucked by life.

In the midst of these reflections, Gato failed to notice a burning barrel rolling down the road until it was too late. He swerved to avoid it, ending off-road. As he tried to restart the car three men appeared from behind the trees, MS-13 tattoos on their faces. Martin was among them. Gato didn’t have time to hide before the two gunshots shattered the car window and left him dead next to Marlon.

~

My phone vibrated, breaking the silence that reigned in the room. The screen illuminated my tired, shaken face. A message stood out below the time stamp: “It’s over,” I swallowed. The knot was finally gone.

Commentary

This fictional short story is based on Elana Zilberg’s Fools Banished from the Kingdom: Remapping Geographies of Gang Violence between the Americas, an ethnographic analysis of gangsters’ deportation from Los Angeles to El Salvador. Zilberg’s work reflects on the deep intertwinement between government-imposed deportation, the geographical physiognomy of San Salvador and the existential positioning of deportees in this changing milieu. Specifically, Zilberg argues that state action in the form of deportation and incarceration influences the foundations and manifestations of identity, belonging, exclusion and ‘otherness’ among deported gangsters, engendering diverging reactions among them to the reshaped spatial environment. Building upon this analysis, the short-story looks at the identity shock perceived by Gato – a Salvadorian gangster who lived in L.A. – after he gets forcefully transplanted into San Salvador by the US government.

Throughout the story, I attribute to Gato some features belonging to Weasel, one of Zilberg’s key interlocutors, such as the green mohawk, his aversion for the term marero, or the fact that he hangs out in La Luna.

This choice allows me to highlight the disruptive impact that Gato’s return has on her life: the attempt to reaffirm his patriarchal primacy contrasts with the independence she achieved while he was absent.

By looking at the vicissitudes of Gato returning to Modelo, this story focuses on one specific aspect of Zilberg’s paper, namely the challenges faced by gangsters deported to San Salvador in adapting to the new environment. Inspired by Margery Wolf’s A Thrice-Told Tale: Feminism, Postmodernism, and Ethnographic Responsibility, my story expands upon Zilberg’s academic contribution by providing an alternative perspective on the consequences of forced migration and deportation.

In this story I shift focus from the spatial dimension of the deportation found in Zilberg’s work to its personal and emotional repercussions. This is achieved by adopting the standpoint of Lorena, Gato’s wife. Observing the distribution of power in her relationship with Gato and how this is reshaped by deportation, the story investigates the struggle of deportation victims and the embedded features of gang violence. This choice allows me to highlight the disruptive impact that Gato’s return has on her life: the attempt to reaffirm his patriarchal primacy contrasts with the independence she achieved while he was absent.

The story also offers a look into the personal and existential struggle faced by gangsters deported (back) to El Salvador. In the second half of the story I abandon Lorena’s perspective, adopting an external narration when following Gato’s last moments alive. The man who left for the US as a breadwinner facing a dangerous future to provide for his family is now returning as a felon, a “fool expelled from the kingdom” to quote the title of Zilberg’s article. I address this topic in light of the recent research in Central America and Africa contrasting men’s experiences with migration and deportation, describing the latter as a much more emasculating and vilifying phenomenon (Galhardi, 2022; Schultz, 2020). The decision of resorting to criminal activity emerges as the only option to earn back that respect and existential purpose lost with deportation. I also touch upon different aspects related to Gato’s struggle to adapt to San Salvador covered by Zilberg, such as the stigmatisation of mareros within Salvadorean society, and the troubles arising from his previous gang affiliation.

References

Galhardi, Renato de Almeida Arao. “Territories of Migrancy and Meaning: The Emotional Politics of Borderscapes in the Lives of Deported Mexican Men in Tijuana.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, December 19, 2022, 136787792211447. https://doi.org/10.1177/13678779221144758.

Wolf, Margery. A thrice-told tale: Feminism, postmodernism, and ethnographic responsibility. Stanford University Press, 1992.

Schultz, Susanne U. “‘It’s Not Easy’. Everyday Suffering, Hard Work and Courage. Navigating Masculinities Post Deportation in Mali.” Gender, Place &Amp; Culture 28, no. 6 (October 30, 2020): 870–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2020.1839022.

Zilberg, Elana. “Fools Banished from the Kingdom: Remapping Geographies of Gang Violence between the Americas (Los Angeles and San Salvador).” American Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2004): 759–79. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2004.0048.

Featured image: “Mara Salvatrucha” by Walking the Tracks is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.