The second book by Gardner and Lewis, Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century, is both an update and a rewrite of their 1996 publication, Anthropology, Development and the Post-Modern Challenge. In addition to the authors’ situated knowledge, the revisited version benefits from a generous presentation of overarching anthropological literature on development. In terms of the theoretical framework, the authors most obviously disassociate from anthropological postmodernist considerations and place a new emphasis on the moral value of development. In order to fully render the progress that development discourse has gained from self-reflexivity, the reality of the beneficial results of anthropology’s engagement with development, Gardner and Lewis rely on human geographer Gillian Hart’s theoretical contradistinction of two kinds of development. The latter discerns ‘little d’ development to be the historical unfolding of capitalist progress as devised by state and inter-state policies. Accordingly, the international post-second world war efforts, as officialised by the launch of the Marshall Plan, and the ‘Development World’, part of which is applied anthropology, are referred to as ‘big D’ Development. Although the abovementioned distinction remains a powerful tool throughout the book, Gardner and Lewis provide ample common ground on the interaction of both ‘small d’ and ‘big D’ development, rather than merely juxtaposing them.

The Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century manages to superimpose a refined anthropological understanding of development on itself.

In chapter two, Applying Anthropology, Gardner and Lewis continue to distance themselves from their previous postmodernist stance on colonialism and power structures in development, and the particularities of UK and US applied anthropology. Instead, the chapter makes a case for a recently applied anthropology, which is first and foremost engaged and then contextual, moving away from any dilemmas of simple advocacy. More prominently in this chapter, Gardner and Lewis argue that practitioners of applied anthropology have overcome their own propensity to breakdown into enumerable categorizations and have accepted their part in the context of development.

Applied anthropology has been largely transformed into an engaged discipline, assuming three major roles as public anthropology, activist research and protest anthropology to truly connect with communities at both practical and conceptual levels.

In The Anthropology of Development, Gardner and Lewis juxtapose once more “postmodern understandings of culture as negotiated, contested and processual (Gardner and Lewis 2015: 99)”, as well as multiple social realities as negotiated, contested and processual products against the iteration of social control, economic inequality and subject construction by development projects. The novelty of the chapter relies in demonstrating that the anthropology of development has reappropriated conceptual and applied space since its mid-1980s discursive turn, as suggested by Clifford and Marcus’s 1986 book Writing Culture, away from “the quasi-scientific paradigms of anthropology, and textual conventions which constructed anthropologist-authors as experts (Gardner and Lewis 2015: 49)” Nowadays, there exists a shared realization that development can be contingent, contradictory and ineffective, and any attempts to denounce the totality of development efforts as reductio ad absurdum are unacceptable. Along the lines of parting away from postmodernism and anticipating future directions, Gardner and Lewis denote the significant increase in the engagement of anthropology with community governance, participation and ideas in the development context. Most interestingly, albeit in a cautious articulation of theory, the authors point at the increased references that scholars and practitioners today make of Marcel Mauss’ economic anthropology, which has brought new attention to the moral and spiritual dimensions of development.

The fourth chapter, Anthropologists in Development: Access, Effects and Control, is a full reproduction of the 1996 original. Subverting the Discourse, raises a question of whether situated knowledge deriving from anthropological practice in development has not seen any changes in the 18 years spanning between the two publications. If their answers remain unchanged, it is worth exploring in depth the framing of questions advanced in this chapter, such as those on dynamics of local power and hierarchy.

When Good Ideas Turn Bad: the Dominant Discourse Bites Back reflects back to the 1996 elaboration on Ferguson’s anti-politics machine co-opting, depoliticising and denaturalising radical development ideas, such as empowerment, gender and development and participation. This time, Gardner and Lewis focus on the project-oriented gaze of development agencies and their overreliance on metrics and indicators, which produce incongruous definitions of development and progress when juxtaposed to local perceptions. Emphasis is also placed on new social movements, such as the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement, for opening up new spaces for anthropologists to engage both critically and constructively. Despite the authors’ refusal to frame anthropology of development in a theoretical context such as was postmodernism, chapter five demonstrates that the need for an anthropology of, both little and big, d/Development should invariably engage on the basis of cultural, social and political changes being processual.

The Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century concludes with a punctilious and succinct assertion of what the authors strive to maintain throughout the book: anthropology of development, like other socially engaged disciplines, has built on its past and surrounding dynamics to become self-reflexive.

As in the 1996 publication, postmodern elaborations on the dualist nature of anthropology and development persist in the book as Gardner and Lewis reproduce sizeable parts from the original. They also argue that despite the discursive turn (Clifford and Marcus 1986), development discourse constantly incorporates novelties to consolidate unfair processes of social change. However, what the postmodernist theoretical framework allowed the authors to term as the crisis of modernity in their first publication the lack of a synchronous theoretical perspective in Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century finds them encompassing the challenges anthropologists face into a wider category as defined by professional knowledge. Moreover, as the unchanged guidelines in chapter four demonstrate, the dynamics of anthropological practice in development remain defined by wider postmodernist considerations. It could be suggested that Gardner and Lewis’s stance draws closely to recent notions of metamodernism. Along metamodernist lines, the authors avoid drawing heavily to postmodernist critique and building their arguments accordingly as a response to the latter, while their emphasis on the moral and spiritual aspects of development definitely make for a modernist perspective. However, without a single mention of the term metamodernism, it is unclear whether Gardner and Lewis wilfully distance themselves from what would otherwise constitute a congenial analytical platform. There is no doubt that Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century is a staple for anyone interested in the subject.

References

Katy Gardner and David Lewis, Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (Pluto Press 2015).

James Clifford and George E. Marcus (eds), Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (University of California Press 1986).

Gardner, Katy and Lewis, David. 2015. Anthropology and Development: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century. London: Pluto Press. 224 pp. Pb: $32.00. ISBN: 9780745333649

**********

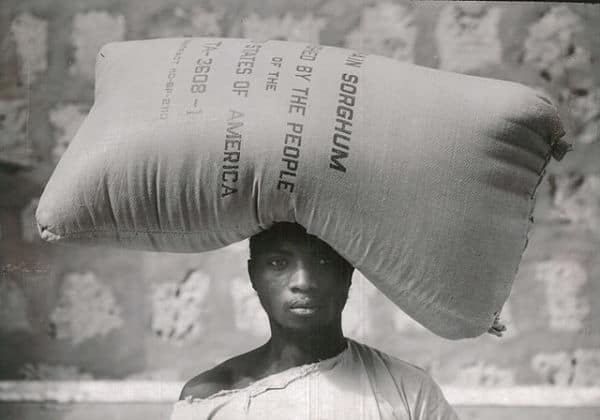

Featured image by USAID U.S. Agency for International Development (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)