The continued economic and ecological crises of recent years have again shown how economists and international leaders have overestimated the ability of markets to expand and self-regulate. In a finite world, dominated by a social imaginary of infinite progress and magically generated wealth (Comaroff, Comaroff 2001), the appropriation of resources and control over the commons are the reasons behind an increasing number of conflicts and structural inequalities (Strang, Busse 2011). To escape from the “specter of impoverishment fostered by unlimited growth benefiting only a few” (Nash 2006, p. 36), we need to critically rethink the relationship between societies and environments. As Melissa Checker (2009) has pointed out, anthropology can offer an important contribution to academic and public debate by inviting and inspiring an in-depth analysis of recent social and environmental changes.

The extensive and well-documented repertoire of possible ways of life analysed through the anthropologists’ lens of fieldwork can contribute by enriching a critical understanding of the current ecological and economic crises. This understanding can also inspire practical forms of transformation of the current dominant ways of life. Here, I would like to draw attention to the mining industry and its complex relationship with environmental issues.

However, to consider mining only from a purely technical or engineering point of view does not give insight into the complexity of the relationships established around the mines, nor help us in fully evaluating the social, political and economic impacts of this activity. The extractive processes are neither ecologically nor politically neutral.

It is appropriate to point out that one of the effects of the mining boom has been the turning of mining sites into places of contention in which a heterogeneous variety of institutional and non-institutional actors – such as NGOs, development agencies, associations, lawyers, journalists and human rights activists – compete with and confront each other (Ballard, Banks 2003; Bridge 2004). These disputes often feature the following two opposing positions: on the one hand, the local communities and their representatives – who seek forms of compensation and want to be involved in decisions that affect the distribution of benefits derived from the exploitation of the local resources – and on the other, the mining companies and international corporations that, for their part, emphasise and publicise the economic and social benefits afforded by their mere presence: more employment opportunities for the population, economic benefits for the national governments’ coffers due to tax paid for mining licenses, and so on (Benson, Kirsch 2010).

As these “benefits” are, for the most part, vague or unfulfilled promises, it is not surprising that the discontent of the people living in the mining areas may sometimes lead to protests or acts of sabotage against those who are locally perceived (most of the time) as usurpers rather than benefactors.

The issue at stake is both material and symbolic. While it is undeniable that the extractive activities require the movement of earth and effectively the changing of landscapes, it is also clear that these changes could contribute to the creation of a new social and cultural order by rewriting the histories of territories (Santos-Granero 1998).

Unlike the pages of a book, however, a landscape is not a blank sheet. Every landscape interacts with the “words” from which it is made through the social actors who inhabit it. The history of a landscape is connected, moreover, not only to an ecology and a local cosmology – as the anthropological analysis of Jorgensen (1998), Stewart and Strathern (2005) and Moretti (2008) in Papua New Guinea’s mining context clearly highlights – but it is also connected to an economy. The trees cut by the large scale mining companies can be commercially viable for the people who live in the areas surrounding the mines and can have social and religious value.

To a point, the same can be said of rivers. They often hold an important symbolic role, and in some cases hold an important political role, as is evident when they represent the boundaries of territories. To change the path of a river in order to facilitate mining operations not only alters the ecology of an area, it also generates disputes and conflicts that can cause long-term problems – as in the case of the extractive industry in Sierra Leone, discussed in great detail in the studies of Fenda Akiwumi (2006, 2012) – and can also generate or perpetuate discomfort, diseases and social suffering.

As a result, it is clear that in order to analyse the so-called “environmental impact” of mining we cannot only rely on statistics or the mere enumerations of chemicals. What are needed are more extensive and sophisticated units of analysis that go beyond the notion, though extended, of “ecosystem” (Bridge 2004). In this sense, environmental anthropology, with its interdisciplinary vocation (Dove, Carpenter, 2002: 61), and the methodology that best characterizes it, namely field research, can make an important contribution to the detailed analyses of local realities, without neglecting the connections (and disconnections) that exist between these same realities and the global contexts to which they are directly or indirectly related.

More than ever, anthropologists now have the opportunity to extend the boundaries of their discipline and undertake fieldwork that explores possible forms of integration with other disciplines (Godoy, 1985) as well as cooperating with social actors that are not necessarily linked to the academy (Ballard, Banks 2003). Overall, they can continue to experiment with new forms of civic engagement and advocacy in support of the communities being studied (e.g. Kirsch 2002; Coumans 2011).

By re-orientating the purposes and methods of the discipline, anthropologists have the opportunity to offer critical and analytical tools capable of subverting the “politics of resignation” (Benson, Kirsch 2010) that large scale mining companies promote in order to attempt to make acceptable and taken for granted the suffering, risks and environmental damages they themselves produce.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article is an excerpt from my chapter: “Capitalismo e risorse minerarie in una prospettiva sferica” in Rossi, A., D’Angelo, L. (eds.), Antropologia, risorse e conflitti ambientali, Milano, Mimesis, pp. 33-48. Thanks to Amalia Rossi, Manuela Tassan and Mauro Van Aken for comments on earlier versions of this essay. None of them are responsible for the views this essay expresses or for whatever errors or inaccuracy it contains. Many thanks also to Julie B. and Ninnu K. for their editorial assistance.

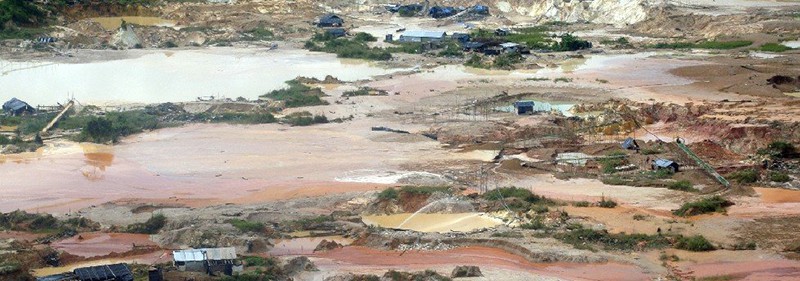

Featured pictures (black and white): Mining community and infrastructures in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Credit: Michele Parodi.

REFERENCES

Akiwumi, F. A. (2006), “Indigenous People Participation: Conflict in Water Use in an African Mining Economy”, in: Tvedt, T. Oestigaard, T., (eds.), A History of Water. Vol. III, London – New York, I. B. Tauris, pp. 49-80.

Akiwumi, F. (2012) “Acqua, cultura e conflitti nelle aree minerarie della Sierra Leone”, in: Rossi, A., D’Angelo, L. (eds.), Antropologia, risorse e conflitti ambientali, Milano, Mimesis, pp. 49-75.

Ballard, C., Banks, G. (2003), “Resource Wars: The Anthropology of Mining”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 32, pp. 287-313.

Benson, P., Kirsch, S. (2010), “Capitalism and the Politics of Resignation”, Current Anthropology, 51, 4, pp. 459-486.

Bridge, G. (2004), “Contested Terrain: Mining and the Environment”, Annual Review Resources, 29, pp. 205-259.

Checker, M. (2009), “Anthropology in the Public Sphere, 2008: Emerging Trends and Significant Impacts”, American Anthropologist, 111, (2), pp. 162-169.

Coumans, C. (2011), “Occupying Spaces Created by Conflict. Anthropologists, Development NGOs, Responsible Investment, and Mining”, Current Anthropology, 52, S3, pp. S29-S43.

Crowson, P. C. F. (2011), “Mineral reserves and future minerals availability”, Mineral Economy, 24, 1, pp. 1-6.

Da Rosa, C., Lyon, J. S. (1997), Golden Dreams, Poisoned Streams. How Reckless Mining Pollutes America’s Waters and How We Can Stop It, DC, Mineral Policy Center.

Dove, M. R., C. Carpenter (eds.) (2002), Environmental Anthropology. A Historical Reader, Blackwell.

Godoy, R. (1985), “Mining: Anthropological Perspectives”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 14, pp. 199-217.

Hodges, C. A. (1995), “Mineral resources, environmental issues and land use”, Science, 268, 5215, pp. 1305-12.

Jorgensen, D. (1998), “Whose Nature? Invading Bush Spirits, Travelling Ancestors, and Mining in Telefolmin”, Social Analysis, 42, 3, pp. 100-116.

Kirsch, S. (2002), “Anthropology and Advocacy. A Case Study of the Campaign Against the Ok Tedi Mine”, Critique of Anthropology, 22, 2, pp. 175-200.

Kirsch, S. (2010), “Sustainable Mining”, Dialectical Anthropology, 34, pp. 87-93.

Moretti, D. (2007), “Ecocosmologies in the Making: New Mining Rituals in Two Papua New Guinea Societies”, Ethnology, 46, 4, pp. 305-328.

Nash, J. C. (2006), Practicing Ethnography in a Globalizing World. An Anthropological Odyssey, Lanham – Boulder – New York – Toronto – Plymouth, UK, Altamira Press.

Santos-Granero, F. (1998), “Writing History into the Landscape: Space, Myth, and Ritual in Contemporary Amazonia”, American Anthropologist, 25, 2, pp. 128-148.

Stewart, P. J., Strathern, A. (2005), “Cosmology, Resources, and Landscape: Agencies of the Dead and the Living in Duna, Papua New Guinea”, Ethnology, 44, 1, pp. 35-47.

Strang, V., Busse, M. (eds.) (2011), Ownership and Appropriation, Oxford – New York, Berg.