As the European elections were taking place, with their horrific results in Greece, France, and the United Kingdom (to cite just a few), I was traveling across Europe, reflecting on the unmet promises and ideals of a unified geography. Brought up during the early days of the European construction, with its Erasmus program, its multiple linguistic exchanges, and its monetary union, I was now journeying on a territory that had gradually become alien.

Looking through the window of the train bringing me from Geneva to Vienna, cutting across breath-taking mountainous landscapes and wild forests, I could not help but feel a sharp contrast between this overwhelming natural beauty and the ugliness of the European political present: fascists of all kinds were entering the European parliament, the National Front had become the first political party in France and a shooting in the Jewish Museum in Brussels had killed four people. In Vienna, I met Indian colleagues who equally worried about their democratically elected far right President Narenda Modi, whose BJP party openly admires Hitler for its treatment of minorities. The biggest democracy in the world had put on its brown shirt and Europe was closely following on its footsteps (or was it the other way around?).

It was somewhat ironic that the various conferences I attended in the course of these two weeks had chosen the theme of ‘diversity’ as an object of academic inquiry.

What was our responsibility, as intellectuals, for what was unfolding before our eyes? Had we failed, cut out from the world as we were in the ivory tower of the Academia, to foresee the catastrophe that was unfolding before our eyes?

On my return to Germany for yet another conference that brought together political theorists, philosophers, anthropologists and lawyers, ‘la crème de la crème’ of the Western intellectual world, I found myself hearing disquieting discussions about the necessity to ‘accommodate cultures’. Not a single time were issues of racism and discrimination brought on the table for discussion. There was evidently a lot of essentialism in the way cultural difference was presented as something to be legally managed instead of simply embraced.

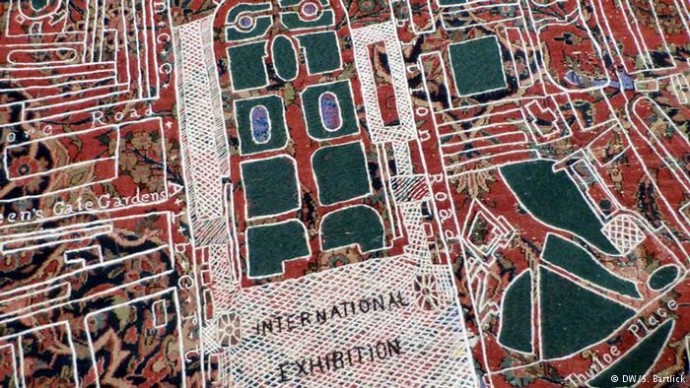

My plea for more empirically and historically grounded accounts both to rights, conceived as framed within larger relations of power and knowledge, and to culture, understood as contested or contestable, which also acknowledge agency and indeterminacy, seemed to fall on deaf ears. And after three days of panels during which knowledge was processed like in a factory, anthropologists were relegated to the very end to offer their ‘cultural expertise’ and ‘ethnographic illustrations’ (for apparently in the ‘post-race era’ there is no more need for anthropological theorizing ‘from below’). Frustratingly, the conference ended with a debate on whether the tradition of Black Pete in the Netherlands could be considered racist.

In recent years, the taboo that used to prevent the spread of racist stereotypes about the ‘Other’ seems to have vanished, disappearing behind well-intentioned liberal discourses about ‘culture and difference’.

As Ghassan Hage argues in White Nation, tolerant multiculturalists and racists both share the idea that the nation is structured around a white culture that they control. If they differ in their respective vision of what an ideal nation should incorporate, both perceive their ‘whiteness’ (a location of structural advantage) as ‘natural’, ‘normal’, ‘human’ and ‘universal’. Hence, both racists and multiculturalists participate in the reproduction of the ‘white supremacy fantasy’.

Luckily, a few days later, a friend of mine drew my attention to an event organised at the Werkshtatt der Kulturen in Berlin entitled ‘Postcolonial Justice’ in which the sociologist Paul Gilroy was to give a keynote. In memory of his old friend Stuart Hall, who recently passed away, Gilroy traced the history of the anti-racist movement in the UK, a movement he conceived as ‘an asset in the consolidation of Europe’s beleaguered democracy’. Moving away from sterile discussions around cultures flattened by legalistic and managerial approaches to identity, Gilroy insisted on the necessity to bring back politics and power relations at the centre of our analytical framework. He highlighted the historical connections between military interventions carried out in the name of ‘democracy and human rights’ abroad and the militaristic treatment of the 2011 riots in London which erupted after Mark Duggan, a 29 year old black man from Tottenham, was shot dead by the police (Duggan’s death was judged as a ‘lawful killing’ by a public inquest in January this year). In this sense, he argued, the history of colonialism could help us better understand our postcolonial present.

Far from being part of an abolished past, the colonies announced the future. They functioned as laboratories where forms of exceptional governance and killing technologies were being experimented and where resistance and claims for justice emerged.

As new ‘black settlements’ started to appear across Europe, the knowledge and technologies developed in the colonies were relocated in the old continent, creating a form of colonialism from within or ‘andocolonialism’. But struggles for justice equally found their inspiration in the collective memory of the oppressed and in the vibrant culture of the ‘Black Atlantic’ (Gilroy 1993). Remembering and archiving this heritage, Gilroy insisted, was essential for imagining relevant forms of action for justice, and for recovering links of solidarity damaged and attacked by the multifaceted forces of neoliberalism. Gilroy’s talk was a good reminder that rights are never given, but are rather collectively articulated, fought for and eventually taken.

As much as an anthropologist, I want to take ‘culture’ seriously, I am also wary of ‘cultural talks’ that tend to represent cultures as bounded wholes, fixed and unchangeable.

The methodological individualism that prevails among many liberal theorists of multiculturalism ‘simply cannot grasp the complex, countervailing pressures, evolving situationally and historically, on individuals caught in the dynamic of minority politics or, indeed, in other social movements in which rights are on the agenda’ (Cowan 2006) . If indigenous epistemologies can help us devise more creative strategies for progressive politics, there is perhaps a need to simultaneously emphasize the ‘radical sameness’ that makes us all part of the human race.

This is certainly one of the messages that some of the artists whose work is currently exhibited at the Ethnographic Museum in Berlin (Dalhem) in the context of the Biennale want to spread. Discussing the relationship between the Self and the ‘Other’ in the broadest sense, this year’s artists have embarked on a broad reflection on how to define cultural property and how museums can become sites of encounters in which curiosity, affect, openness to experimentation and political reflection are given equal space. Interestingly, all of them have strove to respond to the contemporary demand for transcultural conceptions of identity.

Alberto Baraya’s work, for example, reverses the gaze of the European explorer, turning Berlin itself into a site of ethnological expedition. The artist ventured into the wild terrains of outhouses, doctors’ offices, and other unlikely public and private venues to generate a personal agglomeration of scavenged plastic (and otherwise fake) plants gathered together in an ironic herbarium.

Bani Abidi’s video installation ‘Funland’ documents the cosmopolitan past of Karachi (the town where she grew up and where she resides half of the year) with images of empty urban landscapes with closed cinemas, abandoned amusement parks and dusty libraries.

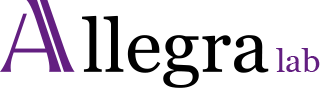

On hand woven Persian rugs, Lahore-based artist David Chalmers Alesworth, explores garden history, advanced warfare and colonial power by inscribing on them a map of London, thus creating a fantastic heterotopia.

These pieces of work are good examples of the productive potential of ‘affirmative sabotages’ – to use Gayatri Spivak’s term (Spivak 2013) – for redefining the terms of identity in the era of globalization. They force us to “think of affirmative sabotage of regularly hybridized European enlightenment thinking, corrected in the process, turning poison repeatedly into medicine, since we are contaminated historically”.

Sources cited

Cowan, Jane K. 2006. « Culture and Rights after “Culture and Rights” ». American Anthropologist 108 (1).

Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard University Press.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2013. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Reprint edition. Harvard University Press.