De-Colonizer: Research and Art Laboratory for Social Change is a project that we, as Allegra Lab, could not ignore when doing our researches for this thematic thread on AAA, BDS and #Palestine. Indeed, the idea of sharing knowledge with a broader audience, not limited to small circles of experts and academics, is very dear to both De-Colonizer and Allegra. We also feel that collaborations between artists and scientists can help us start imagining a different world. But in the context in which De-Colonizer operates, this mandate is perhaps even more crucial. We sat down with Eleonore Merza-Bronstein, one of its founders (and an anthropologist like us!), for a virtual conversation on the importance of knowledge, art and performance for social change.

De-colonizer was launched in January this year. Can you share with us the background story that led to the creation of this venture?

Eleonore: De-Colonizer was born from my encounter with Eitan Bronstein, the singular paths we have taken in terms of our own identities, the solid wish to dig into collective and hidden memories for more acceptance and recognition of the “other”, and our strong common hope to live in a better world where justice, equality and freedom won’t only be words.

Eitan founded an NGO called “Zochrot” in 2001 which aimed to raise awareness about the Nakba in the Jewish Israeli public, and was its director for more than 10 years. Since then, most of the main figures of the organization have left and it has reshaped its political work. In the light of what was already achieved, we believe that there is still a lot to do to raise awareness and continue exploring and enriching the change in discourse on the Nakba and on the right of return of the Palestinian refugees in Israel. We also aim to put the Nakba in the frame of a broader colonialist project: it’s one of its darkest moments but an episode of a wider political project nonetheless.

60 Years of The Catastrophe (Drawing by Latuff2, DeviantArt, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Our position is that there is not only “a” knowledge, produced by “specialists”. We also think that even if it’s important to gather information, it is also primordial to continue, as activists and experts, producing new materials and bringing them constantly into the public space; in our case our targets are the Israeli society itself and the international community, which is why we published all our materials both in Hebrew and in English (and from time to time, in French and in Arabic).

De-Colonizer is conceived as a laboratory, a locus of ongoing experimentation and activity, a junction of research, creativity, archiving/documentation and the body politic. It is a virtual laboratory which transcends political and symbolic borders to create a new extraterritoriality hosting various kinds of tools and projects to challenge the colonialist nature of the Israeli regime. De-Colonizer is the encounter of two spheres that usually mistrust one another: academy and activism.

It’s important to mention that it’s not the encounter of one activist and one researcher, but rather that of research and the political that we both endorse: we are not ashamed anymore to blur the borders and to be researchers and activists.

We don’t believe in the myth of “objective” research, disconnected from the political reality: no one decides to work on a subject by chance and it’s certainly not by chance that we are working on Palestine / Israel. That’s why we define De-Colonizer as an alternative research center on Palestine / Israel, aiming to bring to the wider audience possible new academic-level knowledge and tools by creatively putting them into the public space. This is a political stance that is dear to us: doing and producing research for all and transcending the traditional circles of experts. This means that we had to re-think our own practices as researchers and re-invent new modalities to restore knowledge to the public, stripped of jargon and made accessible. We document all our actions / performances / productions and make sure that they are spread through social networks and media. Both our website and our Facebook page are updated on a daily basis, reinforced by a monthly newsletter and various contributions to mainstream media.

We founded an art gallery called “Illegallery 81” that hosts artists / performances dealing with issues of contested space, physical and symbolic boundaries, (il)legitimacy, (re)appropriation and (re)invention of shared public spaces. Illegallery 81 also hosts many of our events and the screening of the short documentaries we are producing. We also believe that public events and performances are effective tools not only to deliver but to produce knowledge. It’s a kind of permanent back and forth. We believe that the tools and the knowledge we are producing are an invitation to dialogue and to debate: we wish all will grasp those objects, will discuss, spread and use them to convince, to change the discourses, to struggle against history’s oblivion and suppressed memories, to finally envision another and equal shared life and a peaceful cohabitation.

A central mission of De-colonizer is to inform the public about the “Nakba”(the ‘day of catastrophe’) or the massive exodus and displacement of Palestinians which preceded and followed the independence of Israel in 1948. You are writing a book in Hebrew (which should also be translated into other languages) on this issue and have organized various events (including guided tours) to make this historical event visible. Why, in your view, is it critical for the public to learn about the “Nakba”? Why this event in particular?

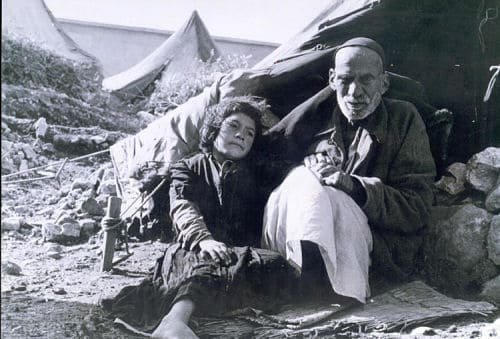

First, the Nakba is not a “day”, it’s a term in Arabic meaning “catastrophe” that refers to the destruction of the Palestinian communities and the displacement of 750,000 Palestinians in 1948 in order to establish a Jewish State. The Nakba did not stop in 1948, it’s an ongoing project since the refugees that were expelled then are still not granted the right of return today.

What we do know, is that the Jewish State that was established in order to provide a shelter for the Jews of the world after the terrible traumatism of the Holocaust has failed: since its establishment, we have been at war. Many Israelis truly want to live in peace; they believed that by building more and more, higher and higher, fences, they would succeed in protecting themselves and that “it” would pass. I believe that this reflects a misunderstanding of the core of the problem – the issue of the refugees and the shared living – and that without addressing it there will be no resolution and no peace. The recognition of our responsibility is the basic infrastructure.

Based on that, we also believe that Israelis living here also have the right to be here and we wish to change the discourse that sees “their” return as “our” end.

We also believe that 1948 marked the reshaping of the Jewish Israeli collective identity as well as the Palestinian’s. On the one hand – and to quote the words of Akiva Eldar and Idith Zertal – the Jewish Israeli collective identity has been transformed into a colonialist one where “the lords of the land” (Adoney Haaretz, 2005), by expelling the majority, took power in the country and switched from one status to another: from a minority, Jews became the powerful majority and became occupiers. Since 1948 maintaining the project of a Jewish State and remaining sovereign has meant more wars, more occupation, more discrimination, more discriminative laws. The occupation did not start in 1967, but in 1948. Nor did it stop in 1967; we are in a constant cycle of oppression and colonialism. Even if we went back to the borders of 1967, which is far from being on the Israeli political agenda, we would still have to maintain colonialism to keep a Jewish State that erected, in its own definition, a clear border – and differentiated means of expressions in term of citizenship – between “oneself” and the “other”.

On the other hand, the Nakba has become the main component of the Palestinian collective identity: it means they became a displaced people, a people of diaspora and occupation. We cannot understand what the situation in Gaza is without remembering that more than half of its population has been Palestinian refugees since 1948. Palestinians that remained within Israel do not enjoy full citizenship and equal rights: they were the majority of the population but have become a minority of second-class citizens in Israel, when not simply deprived of citizenship in Lebanon for example.

Expulsion continues… (Photomontage by falasteenyia, flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Without coming back to 1948, without knowing, recognizing and acknowledging our responsibility in this tragedy, we can definitely not understand the current situation, its constant cycles and counter-cycles of violence; and without redressing the core of the problem, we cannot address any serious discussion to resolving this conflict and living in peace and reconciliation.

The book Eitan and I are currently writing (in Hebrew and French, to be translated into English and Arabic) focuses on the journey and struggle of the last 15 years to reaffirm that the Nakba is not only a Palestinian history but also a part of ours, as perpetrators, and reflects on the efforts made to change the discourses on the Nakba and the right of return of the Palestinian refugee to Israeli society. The book provides a description and analysis of the different modes of activity which shaped this political language based on a unique combination of four elements: creativity, research, documentation / archiving and body politics.

Mapping the “Nakba” is another central project of De-Colonizer. Can you tell us a few words about the “Nakba map” and of its relevance for your broader objective of decolonization.

Mapping the Nakba has become a central project of De-Colonizer but I must give the whole credit of this project to Eitan who has led it for years and has worked on several other counter-mapping projects. The Nakba Map is really his project and it’s the only one of its kind in Hebrew (published by Zochrot). The current Nakba Map is the updated and second version of the initial Nakba Map which he also researched and produced.

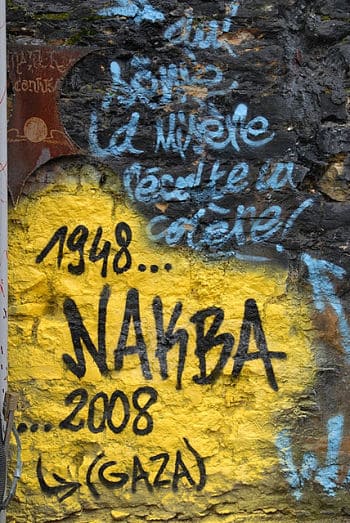

Photo by thierry ehrmann (flickr, CC BY 2.0)

This map shows the 601 Palestinian communities destroyed by Israel during the Nakba, and the 26 Jewish settlements that were destroyed in 1948 by Arab armies (none of them by Palestinians, some of them rebuilt the same year). In addition to those numbers, the map shows the 20 Palestinian communities partially or temporary expelled during the Nakba, the 57 Palestinian villages destroyed by Zionist colonization of the country before 1948 as well as the 3 Jewish settlements destroyed and rebuilt before 1948. The main colonization period was, without doubt, the Nakba in 1948, but we don’t see the Nakba as an isolated event, though it was the principal and the most violent; it must be put on an historical continuum as an episode of a the whole Zionist colonialist project upon the territory it believes is ist own. That’s why the map also marks the 6 Palestinian villages and the 194 Syrian villages destroyed by Israel in the Golan Heights during the war of 1967. As Benny Morris showed, after the war of 1948 most Israeli leaders stated that they should occupy the whole country and pushed for the completion of the project in order to “finish the job”. The war of 1967 was the opportunity to extend control “from the river to the sea”, which is why settlements were encouraged or authorized in the Occupied Territories: they are not meant to be given back.

We are not the only – nor the first – ones to point out that Israel, like all the other countries over the world and in particular colonialist ones, also has its “black pages” of history and that part of it is denied and suppressed. Moshe Dayan himself, when he was Defense Minister, did not hesitate to declare in a speech he gave in the famous Technion Institute: “(…) Jewish villages were built on top of Arabic villages. You don’t know the names of those villages and I don’t blame you for it, because books of their geography do not exist anymore. And not only do those books not exist anymore but neither do the villages. Nahalah has replaced Mahalul, Kibbutz Gevat has replaced Jubta, Kibbutz Sarid has replaced Hanifas (…) There is not one single place in this country that didn’t have an old Arabic population (…)” (Speech reported in Haaretz, April, 4, 1969).

Decolonization is not a one shot project; it’s a project involving long and constant work. The changes we are aiming at are political (and cultural on symbolic levels) so it requires persistence and education. We believe that in the frame of suppressed memory in Israel, it’s our responsibility to bring this part of the history to the attention of the public, although it’s certainly painful and uncomfortable viewing.

You regularly collaborate with artists to trigger debates. In March this year, for instance, you worked with Devora Neumark on a performance entitled “Mansura Revisited”. Why, in your view, is art an important medium for initiating dialogue? How was this performance received by the public?

It is not particular to De-Colonizer of course, but we believe that art can provide very efficient tools to bring people to think about, to challenge and to re-think what they believe they already know. We believe that art and performances can definitely spur the public to critical thinking and dialogue: they are an invitation to a much less passive position toward “the knowledge” or “the truth”, and allow us to be much more active, not only by participating but also by analyzing in a unique and personal way what the art piece / performance is doing to our own knowledge.

In the frame we are working in, colonization is very rooted in the Israeli Jewish identity, and we aim to make our society think again about what we really know – or think we know – as colonizers. By the way, this applies in many colonialist contexts and not only to Israel.

De-Colonizer has hosted a performer artist from Canada, Devora Neumark with whom we have collaborated, producing an art piece entitled “Mansura Revisited” which is part of a much bigger art and research project we are currently working on in the Occupied Golan Heights in collaboration with Golan for the Development of the Arab Villages, an NGO from Majdal Shams. This project focuses on Mansura, a destroyed village located some 10 km south to Majdal Shams.

Mansura is my father’s village so I have a personal story there. It is one of the 200 communities destroyed by Israel after conquering Golan in the 1967 war. Mansura (Al Mansura) is one of the 12 Circassian villages that existed in the Golan up to that war and had been inhabited by some 1,100 persons until then. Occupied Golan remained a geo-political dispute between Syria and Israel and it’s obvious that a peace treaty between the two States may take place only after Israeli withdrawal from it. The residents who have been displaced from Golan’s communities are Syrian citizens who have found new homes in their own country, so they aren’t and don’t define themselves as refugees, in its classical definition. This, among other reasons, led to the situation that these local communities didn’t develop projects to maintain the memory and heritage of their villages. This is leading to a permanent loss of the different cultures that flourished in that region and part of its history.

Our project aims to document and teach the local history to maintain and to keep alive its memory and to expose the current situation of Occupied Golan.

Our performance with Devora Neumark was the first piece produced for this project. It is a multilayered life / art project involving the living histories of several generations. It is at once an aesthetic inquiry into the role that the beautification of home plays for refugee populations and a socio-political exploration of the right of return, which is lodged in both the public sphere and the familial dynamics of the participants.

The first part of the performance was spent cleaning up a room in the school ruins, all that was left of the village, which had been turned by the Israeli army into a dorm for its soldiers during the war. The idea was to make this room as beautiful as possible, ready to receive visitors; a metaphor for the welcome return of the refugees. The second half of the performance was devoted to the beautification of the room and conversations with family members by Skype, and with Druze local neighbors that we invited, along with processing the emotion stirred up by the experience of it all.

The video focuses mainly on Devora’s cleaning and beautification gestures. The process is contextualized, however, with visuals of the United Nations presence and military access warnings as well as the sounds of bombing heard from only a few kilometers away. “Mansura Revisited” was not performed in a vacuum; the ruins of Mansura cannot be abstracted from the contested physical and psychosocial geographies. As an artwork, beyond the living memories of the live art performance, “Mansura Revisited” continues to circulate as a video projection / installation. The video critically and poetically engages with the role that aesthetics can play in regional decolonization while pointing to the symbolic and physical legacies associated with expulsion and occupation.

It was published on our website but will be launched in Majdal Shams and then in Tel Aviv in the frame of the whole project in a few months.

In the near future, your website will offer various conceptual tools that you will put on display and share with your readers. This initiative made me think of the OA journal Political Concepts : A critical lexicon which aims to broaden the scope of what counts as “the political”. Is it what you are trying to achieve via the concept work De-Colonizer sets in motion?

First, we believe that everything is political. Our research is political, the context in which we operate is political and the tools we are creating are political. It’s not a secret either that our aim is highly political.

I’m developing and leading this specific initiative, and the fact that I’m an anthropologist has, without a single doubt, something to do with that. Anthropology has changed my life. I’m not joking. I was 16 years old when I discovered anthropology in a philosophy class. I still bodily remember the shock I got while reading “Race and History” by Claude Levi-Strauss for the first time. For the first time, I was reading a brilliant and limpid argument against racism and in favor of shared living; I remember thinking that this author was summarizing many ideas that were jumping about in my teenager’s messy brain. This day, back in September 1996, I knew I would become an anthropologist.

Since then, being an anthropologist has certainly become a strong component of my identity, one that is in constant motion, a kind of pillar upon which I’m building my political and professional involvement as a researcher and as an activist. I believe in popular education and I think no subject should only be discussed by “specialists”. On the contrary, I believe that everyone can understand everything if she / he has good tools. It’s particularly relevant in the case of Palestine / Israel: too many people have already internalized that it’s “too complicated” for them, that it’s simply “not for them” whereas the conflict is making the headlines on daily basis.

The huge number of “specialists” using contradictory facts and arguments usually discourages people from seizing the matter and to allowing themselves to take part in the discussions. De-Colonizer is not a school and does not aim to lecture; it just wishes to make tools accessible to the public by presenting academic and serious non-academic work connected to the issues we are working on. It’s a political stance that is very dear to us: doing, producing, discussing research for all, and transcending the traditional circles of experts.

Finally, in a few weeks, the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association will take place in Denver. As an anthropologist working on the Israel-Palestine conflict and as an activist, what is your view on the BDS (boycotts, divestment and sanctions) campaign? Do you personally support this campaign and do you think members of the EASA should get involved in it too?

Many times we hear people saying that boycotting the academics is problematic since it also silences “alternative” and critical voices from Israel. We agree that it’s problematic and we acknowledge there’s a price to pay but, while looking at the general picture, we must remind ourselves that the Israeli academy mostly very actively supports the colonialist aspect of the Israeli regime. Disconnecting the production of the knowledge from the political surroundings, as if the academy and academics have nothing to do with politics and society is a very problematic procedure. We believe that people that produce knowledge should also be involved in building a better and equal world.

Over the years, we have also, and sadly, understood that the change will certainly not come from within. Only strong pressure from outside will help us to overcome the situation which we are in. The great majority of Israelis are far from being ready to give up their privileges, exactly as white South Africans were not ready to do so until the fall of the apartheid Regime.

Knowing the constant obstruction of Palestinians’ right to education, knowing that some of our Palestinian colleagues are prevented from studying, accessing education, talking and attending conferences based only on the fact that they are Palestinians, knowing how restricted their movements are, knowing also the daily censorship and threats to those Jewish Israelis academics who are critical of their own state policy, we support the BDS campaign and call upon the AAA to endorse it.

This international campaign is in our eyes the most important and promising civic campaign to end occupation and make a difference here.

As Jews and allies, we are also glad to see more and more organizations like Jewish Voice for Peace endorsing the BDS campaign and helping to tackle the fallacious and shameful argument which consists in presenting BDS as a new form of anti-Semitism but is simply a new way to silence all criticism against Israel. We are aware that unfortunately, some individuals are exploiting the BDS campaign to promote their racist message and their hatred for Jews but it is unacceptable and dishonest to heap opprobrium on the whole movement. Together with our Palestinian and international comrades from the campaign, we are very clear on this point and don’t miss a chance to say loudly that there is no room for anti-Semitism in the BDS Movement.

Featured image by falasteenyia (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)