A cold, wet, arctic wind graces the concrete skin of the Tenderloin. Pill Hill, the three-block stretch of inner city urbanity, along Leavenworth Avenue and between Turk and McAllister streets, known by the locals for the cornucopia of illegal pharmaceuticals made available by out-of-town pusher men, lies inhabited at this particular hour only by a winter howl, some trash, and a few unlucky homeless. Corner stores, the way stations between destinations at this hour, see a few alcoholics, desperate grazers, and tourists pass through their thresholds, peruse the mostly dry goods, make a purchase, then depart back out into the stormy streets. The stony edifice of those who man these urban wellsprings, night after night, peer out at each passing consumer like the gargoyles that used to adorn the masonic doorways of cathedrals, town halls, and other esoteric meeting places. As they speak, the price of every purchase is gurgled to every consumer, as if they were reminding of us of each passing sin. The consumer repents and is released.

Other than the corner stores, the glowing beacons in the night, there are a handful of bars, hostels, and cheap hotels. The bars rarely deviate from what’s expected of your typical dive bar — wood paneled, about as large as most people’s first apartment, a jukebox in the corner, maybe three beers on tap, and potentially either a pool table, a stage, or darts. The hostels are often inhabited by an invisible population of young Europeans on long term holidays. The cheap hotels, on the other hand, are inhabited by an equally invisible, yet more proportionally ignored, population of very low-income residents, strung-out addicts, and medically indisposed individuals.

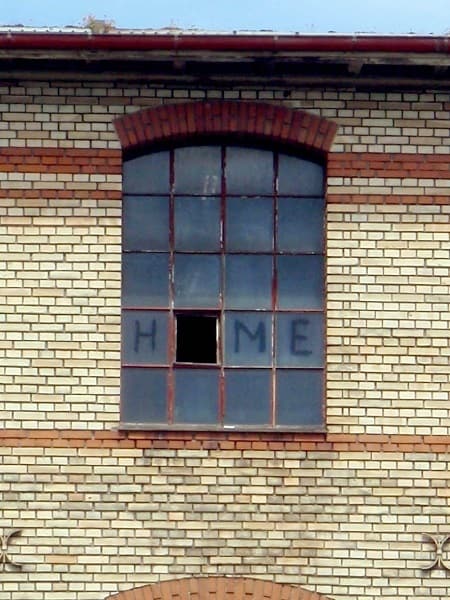

Photo by Ryan McGilchrist (Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0).

All of them are fighting against this harsh environment.

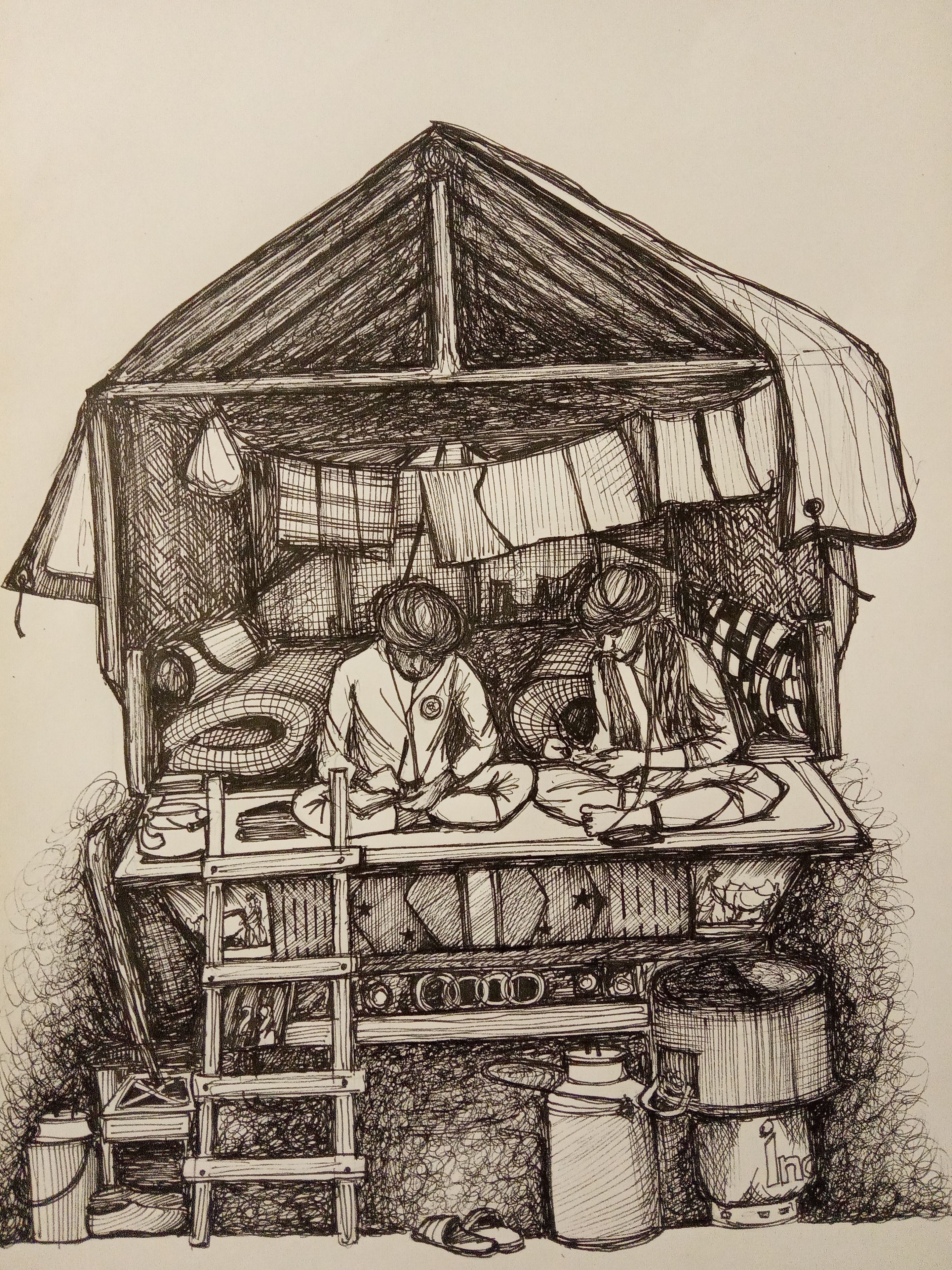

There are a few peculiar places in, what one of my friends’ calls the Tenderloin, “The Last of The Wild West.” On Turk Street, between Taylor and Jones, there is what would appear from first glance, a storefront. Avert your eyes upward, as if you’re asking some God in the sky for repentance, and you will a see a matte, grey gun-metal sign with the words “DRUGS SF” seemingly burned into it. My first guess at the type of operation they have going on, just behind some black metal bars and single pane windows, is that of a needle exchange. Word on the street, however, is that their particular operation is more all-inclusive. From how the sidewalk appears, during days when it is considerably less stormy, it would seem that the word on the street, as always, has more merit than than most would give it.

On this particular Tuesday night, however, I find myself across the street from Aunt Charlie’s, in a church. It is three days before Christmas and it is a holiday party at a Rescue Mission, at which I provide social services to the homeless and low-income individuals of San Francisco and the surrounding areas. I am watching a short, Phillipino man, in light blue, denim jeans and a black shirt on which the words “SF City Impact” are printed. He is the pastor. He is their pastor, Pastor Ralph. Pastor Ralph is speaking into the microphone, trying to get above the noise of those who have seemingly found God through work, and succeeds in getting the joyous crowd in playing Two Truths and A Lie. It seems that, as I have arrived late, that I missed the part of the night where each member of the congregation wrote out two truths and a lie about themselves.

——————————————————————————————————————————

My first case, working here, was an older, blind, white woman. She came up to me, with a cane, and sat down with her mail, asking me to read it for her. Her mail, like any mail, told her story. Frankly, they were all healthcare and municipal letters. Nothing personal. I would look up, occasionally, into her glazed eyes or at her mangled, grey, mane of hair. Her hair looked like it had just frosted over, and not grayed. Her eyes also seemed to have frosted over a bit. It looked as though they had soaked in too many sights like a sponge and simply couldn’t hold any more of this world.

Where she may have, at one point, received love letters, now she only receives mail from those wanting to collect their dues.

She is alone. She is alone and has gone blind from cataracts. She was too poor to afford the necessary healthcare. My supervisor informs me that it is our job to circumvent the city’s infrastructure so that she is no longer alone, blind, and without care. Despite these facts, however, she is unwilling to accept the fact that she needs someone to watch over her. Her condition, while physical, had consumed more than her eyes. It had consumed her sense of survival. Light had only become a memory, and deliverance from the darkness seemed unlikely.

When any living thing is placed in an unfamiliar environment, adaption takes place. What happens though, when its not the environment that changes, but instead how we see it? How we smell it? How we listen to it? Do the stories we tell ourselves disappear?

These stories are often untold, but that does not mean that they are not lived and etched into the minds of those who inhabit the streets of our cities. Told to themselves, often without any other audience, the pages of years that pass them by, filled with words and spacing foreign to most, may as well be as unreadable to us as this page is to the blind. Poverty to them, these first world inhabitants, is a sight unseen, and a condition undefined, by virtually everyone. The internet, an engine of outrage and then, ultimately, antipathy, lacks a proper definition for their condition. Scholars pace ivory floorboards, buoyed by the two breaker waves of industrialism and late stage capitalism whose curl and crash rips others into the sea.

It is in this liminal middle place, between sea and shore, torn between the grasp of one and the harbor of another, that most find themselves. Struggling, screaming, crying for recognition, until their voices become hoarse, and either the tide relents or they are pulled under. The cityscape, static and lifeless, weeps for no one.

The stage for this tragicomedy to play out is the spaces between buildings, between doorways, and under bridges. The environment we build, as toolmakers and deacons of stone, glass, and steel, becomes the foreground for love, loss, and connection. Through this manipulation of fundamental elements, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and neon, and through a perceptiveness towards nature, the winds, the rain, the sun, and the heat, civilization takes rise.

The tragic irony lies in the abundance of fruit from our labors. It is in that abundance, the space between buildings, doorways, harvests, that the seeds of poverty and need are sewn.

The comedy is that of errors, of blind decisions, and of misperceptions. No civilization ever to have risen from the earth has ever eliminated poverty. That is because poverty, in and of itself, results from civilization. Civilization and agriculture, two of humanity’s greatest achievements, manifestations of our will to survive and reproduce the wild, have bred their own dangers.

The blind woman is looking towards me, maybe at me, possibly through me. To her, I am an echo in a cave, sounded from the mouth, a reminder of a different world. Who knows how long she, and others like her, will be stuck here, or how they will leave.

——————————————————————————————————————————

The building’s doorway lies behind a gated threshold, which is often attended to by a stony-faced acolyte of the church. Inside is modesty. A white tile floor, broken up by a garish brown-tiled cross, a lovely piano, a stage, and a red curtain, separating the kitchen, social services, and the clinic from the barebones church hall, are the only material extravagances here. The only real shared trait of those here is that they’ve decided to journey through the stormy Tenderloin and, instead of entering a drug den or a bar (at least, on this particular night), cross this particular threshold into the building.

These people really believe, in the Christian idea of God. Somewhere, in the prefrontal cortex, the attention, executive action, and memory river of the brain, lives their religion. Through their actions, the focused repetition of memory, symbols, and ritual, is created the community standing before me. That community is, most lazily, described as made up of the quintessential “happy Christian,” a sort of folk archetype that makes up so many church congregations throughout America. This is the last place I would have ever thought a gay, genderqueer anthropologist to have turned up.

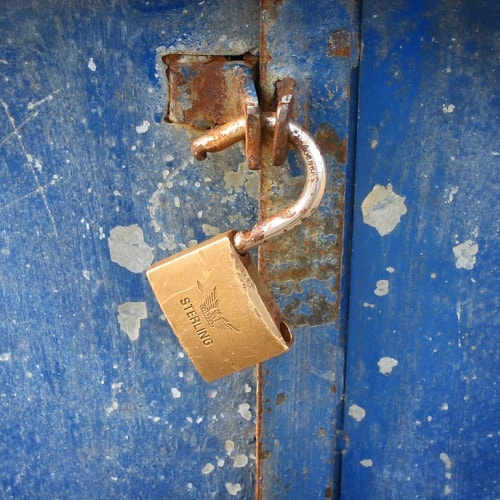

Photo by Martin de Witte (flickr, CC BY 2.0).

Perhaps a better description would be that this community’s devotion has an anesthetic effect on much of what they see on a daily basis. Frankly, I see why it’s necessary. Between cases, often those who work here will pray with their patients. Not all healing is physical, or social, I suppose; there are those who are very alone, who’d like to know that someone out there cares about them.

Meanwhile, I can often be found talking to someone about the pants they need. Or the socks. Or the underwear. Or the shoes. Wrapped in acrid, old clothing, the need for clothing is possibly the most often overlooked, ironically. Weeks spent in the same few pairs of underwear, pants, and shirts, often without access to showers, laundry, and, in extremity, bathrooms, can sometimes tar clothing with unwanted filth. As with so many of their needs, it may seem simple, ordinary. As with homes, however, clothing is another thing we often take for granted in “civilization.”

——————————————————————————————————————————

The congregation is drinking root beer. The storm rages on. The pastor is preaching God’s love with one of his 6 children, a small girl, ribbons in her hair, at his feet, clinging to the leg of her father. There is a weary cheerfulness that lingers in those that work here, much as I imagine there was in the hearts of those who first arrived in San Francisco.

The trade here, as far as I can tell, is that of endings. Heaven, hell, the birth of Christ, the death of Christ, or the new year, there’s a type of over-anticipation of the passing through a certain threshold.

And here, in this place full of sinners, saints, and redeemers, that type of anticipation, that anxiety, of the uncertain cuts deep.

What is promised, what is hoped for, is deliverance. Deliverance from a needle, deliverance from blindness, deliverance from love, or madness, gone wrong. I wonder, sometimes, when they pray, in hushed voices, if God doesn’t answer because he can’t hear them, and wants them to speak up. I may humor, but many here do question their place, and why God hasn’t spoken to them on an individual, personal level.

Deliverance, however, is another threshold, another doorway, to an uncertain place. When faith is either rewarded or betrayed, it goes somewhere. When it is rewarded, the faith is reinforced. When it is betrayed, it can be broken. Either way it is reborn, in new clothes, and within a new home.

The truth is, many here are at the extremes of their being. Many have come here, myself included, through simple twists of fate. The death of a loved one, the abandonment by a parent or family, a legitimate business deal gone wrong, a horrible accident to the body, advanced age, these are all incredibly common stories of the homeless. It can happen to anyone. Drug use is merely symptomatic of underlying turmoil.

Photo by eric molina (flickr, CC BY 2.0).

When it happens, when the roofs caves in, when the fires consume the photographs, when the paint is stripped, when the flowers in the garden die, what is left of a home? Where do we move on to? Where or what will be delivered to? When we are pushed to the very extreme limits of faith and hope?

The very extreme of ourselves, find ourselves bare, in the wild. Faith, barely clinging, becomes the cloth with which you are clothed. Hope, the roof over your head.

Hope, and faith, ultimately betrays the believer, in that all things must come to an end. The way of nature is multiplicity and adaptation. As circumstances change, as homes fade and loved ones depart, so too must certain types of faith and hope. These things must bend, or they break. Faith, love, and hope are reactions to the uncertain, to the ever changing environment.

What lies deeper, beneath the shapeshifting, ontological outlooks, beneath the dogma, beneath the love, the hate, the hope, and the despair, is something more, something unchangeable. Each and every one of us, on the inside, we’re bigger than the religions, the loves, the hates, the hopes, and the despairs that haunt us.

No one moment, month, week, or year’s fill of anxiety, grief, depression, dissociation, sadness, euphoria, contentedness, or happiness defines us entirely. These things are a river, reflecting the sky above, and we are that which float on the current.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Gallows humor is another trade here. Jokes about death, drug abuse, and mental health permissively decorate the language as much as the crucifixes decking the halls of the church. A lack of material wealth certainly informs a certain spiritual wealth.

Those however, that I have seen successfully get off the street, or deal with a major health problem, or get that job, often find themselves hitting a glass ceiling. If they get off the street, they may find themselves in an SRO — usually a room of an older hotel that has been rezoned for longer term living. While not particularly wholesome, I have found them to at least be lively. For most though, it is the end of the line (although I personally hope it is not). That is the story of class mobility.

San Francisco is an active war against the homeless, make no mistake. The local government is cleansing the streets of encampments. Residents, mostly new, can go viral by posting rants against the poverty they see, seeming void of any empathy. More insidious itself is the abuse with the system designed to help them. Non-profits competing for funding resources often do not work together in tandem to face the issue. SRO owners abuse the power they’ve been given, and shelter workers steal while some slumber. These are only the threats faced by the environment and not the threats that come from other homeless, pimps, dealers, and the massively dysfunctional bureaucracy of the welfare system. This is what first world poverty looks like. Compared to this, faith is simple.

The party is over. Christmas will come, as it always has, and there is nothing we can do to stop it. We are not hoping for Christmas, instead we need it to come as a break from the winter, from the isolation, and from the cold. In the minds of the congregation, memories of Christmas past, in homes, waking up to families, presents of toys and clothing.

Deliverance, served. The cycle of seasons, of love, and of memory being renewed. For better or worse.

I look around, and across the room I see the my first client, who has become a volunteer since I last saw her, and she is no longer using her cane. She is no longer blind, after a surgery we helped her through. Apparently, my supervisor tells me with a laugh and a smile, on the day he visited her, not longer after the surgery itself, in the middle of the euphoria provided by the long journey through the darkness, she turned to him and said, “I never realized you’re black!” Sometimes, life just surprises us.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Postscript

Much later, after my departure from the concentric circles that make up the social services of San Francisco, SF City Impact, and the home that I did not know was home at the time, would go through a tectonic shift, regarding its organization. Christmas passed into Lent, and with Lent, a purging of that which bears weight on the soul. Of this purging, my departure was one of the first.

Photo by Daniel Lobo (flickr, CC BY 2.0).

I left, amicable with most of the organization’s members. It was with my supervisor with whom I fought, both victims of what I would learn to name as “empathy burnout.” I had stretched myself too thin over the process by which one performs ethnography, and he had stretched himself thin over the process by which one performs social work and leadership. After a brief, yet aggressive and hushed berating from him, I left. I walked out. Pass the cross on the floor, through the door, and out of the threshold.

Three months later, I found out that he had relapsed, and the social services department had closed. On my return, I find just four walls, a floor, and a roof. Once charged with symbolism, with crucifixes and computers, simulacra for beliefs and thought processes, and fervent with personal connection, now a void, a vacuum. The blinds are closed, and those in the light had fallen into darkness again, at the cost of the deliverance of others. I wonder, is this deliverance? Is this Grace? Or is it the cycle renewing itself?

Homes are fragile things. They appear, from the inside, to be safe, unchanging, and sound. Four walls. They are most present in the past, but the past is just our memory, and the memories we share with others. A floor. They are ourselves, they are our environment, they are the people around us. A roof. These memories, our relationship with the passing of time, are vulnerable to change, to decay and adornment. A doorway, with many people waiting to go through.

Featured image by Nick Carter (flickr, CC BY 2.0).

This soliloquy of thoughts and profound observations are just wonderful!! Very emotionally provocative!! I love it! Write more.