In this essay, Afghan American artist Aman Mojadid reflects on a series of installations entitled “Conflict Chic” he exhibited in a solo exhibition in Paris in 2011. He discusses the imagined geographies born out of the Afghan wars and the search for a post-Orientalist tradition in the post-9/11 era.

At a solo exhibition in Paris in 2011, I showed a work titled Conflict Chic 1 & 2. The piece was a critique of how the war in Afghanistan, and the expatriate life that accompanied it, had, over the years, become cool, artsy, and fashionable. In Hollywood, any number of movies could be found with some focus on Afghanistan and its war, or at the very least a reference made to it such as ‘like in Afghanistan’, while in Kabul expatriates could wear the latest in chic, overpriced neo-traditional fashion to the various dinners, parties, or concerts they attended.

The creation of Afghanistan as ‘conflict chic’ was also furthered as foreign governments began throwing money at a variety of art and culture-oriented projects through public diplomacy grants as part of their propaganda campaigns, trying to demonstrate how far Afghanistan had come since the invasion of the country in 2001. Although this included a range of nations such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, it was heavily led by the United States of America, whose public diplomacy budget totaled, according to the special inspector general on Afghan reconstruction, US$111 million in 2010−11 alone; up from a total of US$1.5 million between 2007 and 2009 (Sopko 2014). Although these budgets covered a wide range of activities, art and culture (under the umbrella of civil society) projects were given priority during this funding period.

These projects included a variety of mediums such as a fictional short film about young, impoverished boys with unrealized dreams of playing the national sport of buzkashi (which got a 2013 Oscar-nomination in the Best Live Action Short Film category, only reinforcing the point about Hollywood made above); a rock music festival (which actually began as a solid platform on which contemporary musicians could express themselves but later became an all-encompassing ‘performing arts’ festival, corralling any and every art form under the sun − because why focus on one thing and do it well when you can co-opt, and possibly get funding for, more?); a documentary film that sought to place every Afghan artist into a life-or-death, good versus evil, battle against poverty, war, and Islamic extremism; and a multi-media project that simply showed the ordinary, though sufficiently exoticized, banality of everyday Afghan life just being lived.

And journalists, of course, could not get enough of stories about Kabul’s ‘first female rapper’ or ‘graffiti scene’, as if there actually was a ‘scene’. The reality, however, being that journalists often exaggerated graffiti’s presence on the streets of Kabul, at times even dragging artists (all the better if it was a woman because that had so much more cachet for international audiences) to funky locations like the now demolished former Russian Cultural Center to spray something on the walls while the cameras went ‘click click’, serving as false witnesses to a growing ‘movement’.

But this was one country, and Afghanistan was unique in many ways, due to the massive war economy that had flowed into it and shaped life and society there – for better and worse. I was curious to see what else was happening in the region, and so I attempted to look more closely at not only Afghanistan, which is where I had the most direct experience, but also at different Othered countries that are part of the broader region of Asia and the Middle East. I use this ‘active’ form of the term ‘Other’ as a tool in order to emphasize how the experience of being Other is an imposed system of differentiation rooted in Eurocentrism, rather than any place’s or people’s natural state. The approach is reminiscent of Arturo Escobar’s use of the term ‘underdeveloped’ rather than ‘undeveloped’ in his arguments related to dependency theory and Latin America in a postcolonial era, whereby he asserted that the Third World was ‘underdeveloped’ as a direct result of Eurocentric policies imposed upon it after the Second World War (Escobar 1995).

Furthermore, and in particular, I wanted to look at countries that were either experiencing conflict themselves, or were somehow part of larger geopolitical conflicts being waged across these regions. However, for the purposes of my argument, rather than only armed battle or a state of war, I define ‘conflict’ more broadly as the experience of various forms of political, social, economic, and personal instability by countries in the regions mentioned. However, I will use the expression ‘conflicted countries’ rather than ‘conflict countries’ partially for the same reason described above − so as to avoid the implication that conflict is in some way natural to any of these places.

Once I started looking, I noticed that the last several years have seen a marked increase in the level of interest given by the Eurocentrics towards contemporary art from Afghanistan, as well as many different Othered countries in Asia and the Middle East, particularly conflicted countries.

This includes work created by artists living within the specific geographically defined border spaces, as well as the broader cultural spaces inhabited by artists of the diaspora. We can see the manifestation of this interest across a variety of initiatives such as the Guggenheim’s MAP programme and planned Abu Dhabi museum, the recently established Iraq, India and Bangladesh Pavilions at the Venice Biennale and the inclusion of Afghanistan in dOCUMENTA(13), to name just a few of the more institutional movements. There has also been a parallel boom in interest by commercial galleries and auction houses for art from these regions, or the artists thought to represent them. All of this has provided a greatly extended platform through which the work of Othered artists from conflicted Asian and Middle Eastern countries could be shown in internationally renowned venues and exhibitions, exposing their work to entirely new audiences and markets.

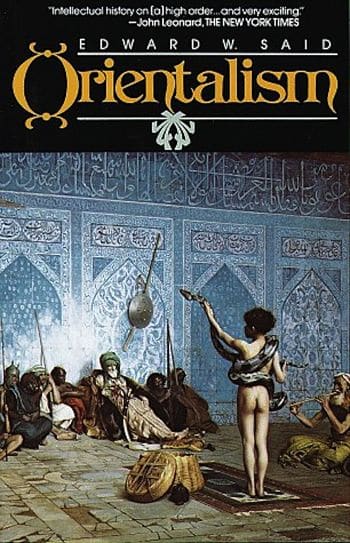

I would therefore like to argue that the increased interest and the relationships created by it cannot be understood outside of Eurocentric models of power and hierarchy rooted in colonial structures, and that can still be seen in postcolonial (though not yet post-Oriental) relations between the Eurocentrics and the Othered. That conflict has become a part of everyday life in many Othered countries that were once under some form of colonial control/influence, subsequently becoming a part of the Othered’s contemporary ‘exoticness’, which can itself be understood as being rooted in these disproportionate historical structures that shaped so many unstable futures. Although it will be possible to also see market influences in this heightened interest by the Eurocentrics in art and artists of the Othered from conflicted countries, I argue that at its core one can still find the old attitudes of civilizational superiority and colonial discovery that led the Eurocentrics’ historical conquest of places and peoples. However, I will go on to argue further that it is also possible that these new spaces within the art world where relationships are enacted between the Eurocentrics and the Othered could provide, though not without difficulty, the type of ‘Third Space’ necessary to begin dismantling old, colonial-era knowledge-paradigms and power structures.

As a start, we should examine these new spaces of interaction between the Eurocentrics and the Othered in light of how modern notions of aesthetic authority, and the subsequent power to represent in the field of contemporary art, are complicated by these deeper, geo-historical relationships. French Marxist philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre has said, ‘(Social) space is a (social) product [. . .] the space thus produced also serves as a tool of thought and of action [. . .] in addition to being a means of production it is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power’ (Lefebvre 1991 [1974]). I would argue then that this social space in the field of contemporary art as discussed above, due to its being intertwined with larger historical perspectives and political agendas (as well as to some extent economic initiatives), sees the same pattern whereby the productive space of Othered artists is also a space where Eurocentrics exercise their power to control and dominate aesthetic and artistic representation.

It is therefore necessary to look briefly at the person largely considered to be the founder of the Eurocentrics’ understanding of aesthetics – German philosopher Immanuel Kant. In his theory, Kant argues that the judgement of taste, or what is to be considered beautiful, might be dependent on a subjective principle but ultimately has universal validity (Kant 2000). This notion of ‘subjective universality’ in the determination of aesthetically beautiful ‘things’ has served as the building block for the Eurocentrics’ approach to knowing and controlling the notion of modern aesthetics. Though on the surface this principle allows for individual or relativist agency in aesthetic judgement, it is in fact rooted in the Eurocentric mindset rampant across Europe during the Enlightenment period of which Kant was a part. By this I mean to say that, although it appears Kant is honouring individual taste, he is not however attributing equal value to those tastes. Instead, he deems that the individual, subjective tastes of the European are the specific tastes that have collective, universal validity.

In other words, a thing is beautiful if it is considered beautiful by a European.

Therefore, the ‘subjective’ viewpoint that Kant was so insistent upon in his philosophy was the Eurocentric subjective, while the universal it was applicable to belonged to everyone else. Beauty and aesthetic judgement therefore belonged to Europe, and from there it attained universal validity for the rest of the world.

This Eurocentric model of aesthetic authority can still be found today in the contemporary art world, largely dominated by American and European curators, museums, dealers, galleries, and institutions. It is their authority to judge not only where the focus of the curatorial eye should fall, but what and whose work within those areas qualifies (i.e. achieves the expected level of aesthetics) to be exhibited and brought into the global art world. We can see further foundations of this attitude in Jean-François Lyotard’s theories on the imperialistic nature of western science. He would look at the arrogance of the West in its belief that their science, such as in the field of medicine, was without a doubt superior to that of other cultures. In that sense, western scientists, doctors, etc. felt they had the monopoly on knowledge in their fields (Lyotard 1984 [1979]).

Again we are confronted with the Eurocentrics’ belief in their own superiority and, in the context I am discussing here, we can see the Eurocentric curators, gallerists, museum directors, institutions and so on with their monopolies in the field of contemporary art knowledge, and how they seek to impose that knowledge on others; it is this imposition of monopolized knowledge that Lyotard equates with imperialist motives and approaches. This sense of authority over judgement contributed to justifying European colonial incursions around the world as missions to enlighten and civilize other cultures, while today the Eurocentrics in the art world are justifying incursions into the lands of the Othered where they impose their aesthetic value systems on works and artists that may operate on an entirely different aesthetic scale.

Since the fall of ‘colonialism proper’ (meaning direct political and military control), many countries of the Othered have themselves fallen into states of near perpetual conflict, driven by a variety of factors such as internal political agendas, poverty, ethnic intolerance, foreign invasion, religious extremism and dictatorial leaders. This adds another layer of complexity to the new Eurocentric interest in Othered art in the sense that widespread conflict in many parts of Asia and the Middle East can serve as ignition points of entry for Eurocentric curators, collectors, gallerists, etc. On the surface, it appears that the impulse comes from a desire to understand the complexities of the region ‘from the inside’, from the creative voices of artists living in (or at least with roots in) these Othered countries where conflict in some form has become a part of their everyday reality. However, it is difficult to dismantle the old colonialist models beneath the surface that are shaped by historical paradigms and continued disproportionality of power/control hierarchies.

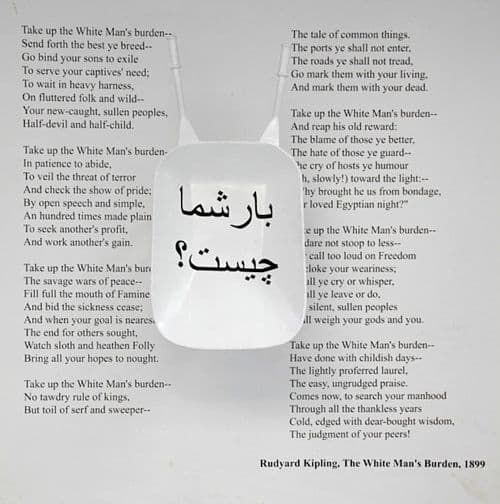

When we see the dOCUMENTA(13) with satellite activities in Afghanistan, the relatively recent pavilions of Iraq and Bangladesh at the Venice Biennale and the Guggenheim’s MAP programme, we should feel compelled to ask ourselves what drives all of these institutions to go so far away, to the lands of the Othered, in order to ‘discover’ or ‘present’ the contemporary artistic practice of these places. If it were just wanting to go where contemporary art is still under-represented, under-appreciated and/or in a nascent state of being, many rural areas in the United States and Europe could offer the same challenge. But that is not where they are going. Rather, they are going to places where they can give a voice to the voiceless, an attitude often seen in Eurocentric approaches to Othered nations, particularly conflicted countries which cannot escape the yoke of the ‘white man’s burden’.

One feels that the Eurocentrics see it as almost a necessity, a humanitarian burden they must bear to show the rest of the world what amazing work Othered artists in conflicted countries can create.

One can almost hear the echoes of early anthropologists, and the Kipling-era colonialists they often accompanied, who set off on adventures to Othered lands where they could explore and discover local cultures. It is as if what was once the white, European anthropologist, locked in global colonial structures and defining for us the noble savage, has now become the still largely white Eurocentric curator/dealer/gallerist/institution defining for us the noble artist − the artist who can rise above the savagery of war and oppression of conflict that surrounds them.

A disturbing effect of this renewed interest in conflicted countries and their Othered artists has been that of the Othered beginning to self-promote and highlight their own Otherness for the benefit of the explorer curator − self-orientalizing themselves to create work that fits the model of what is expected by Eurocentric interests. Artists from conflicted countries of Asia and the Middle East have therefore become the spokespeople for a place and a people that the Eurocentrics need and want them to be. Questions are asked of them such as ‘What is Afghan about your work?’ or ‘What is Pakistani about your art?’, questions that are never asked of western artists. ‘What is American (or French, or British, etc.) about your art?’ is not a question ever heard. This is because the Othered are still believed (even when they convey individual, conceptual ideas through contemporary artworks) to be of one mind, one thought, one homogenous ‘local’ entity that lacks the individual diversity thought to be inherent in the developmentally advanced Eurocentrics. The fact that this has become a part of these new relationships only reinforces the stereotypes that have dominated Eurocentric attitudes towards Othered nations and their people for decades.

This blanket perspective on entire regions and peoples was a hallmark of colonial endeavours and Orientalism as a whole. The attitude has not disappeared. And unfortunately it is becoming adopted by many artists in these regions, believing that by creating what is expected of them they will eventually reap the rewards of their loyalty through participation in the Eurocentric-dominated exhibitions and markets. But is it truly necessary that the Othered artists create work that directly reflects the exoticized conflict they are somehow deemed to be an inseparable part of? Must they be a ‘voice’ of their people in troubled times, just waiting to be heard? What happens if an Iraqi artist for example wants to paint something else, something ‘un-Iraqi’ (as defined by the Eurocentrics), something abstract and without a sociopolitical message? Would it be judged on the quality of the work or only on whether it says enough about the artist’s troubled identity and environment?

With so many factors playing a role in shaping these new relational spaces between the Eurocentric art world and the Othered artists, it becomes necessary to also look briefly at how perhaps the Eurocentric-dominated art world has simply become bored and saturated with what is being produced in Europe and the United States and is therefore looking for different perspectives in art from conflicted countries in Asia and the Middle East, and subsequently for new products for their markets. It is a fact that some ‘emerging markets’ seem to coincide with these conflicted Othered countries and have become a very hot topic in the business world. Why wouldn’t we see similar inroads into these new, potentially economically fruitful, zones by the commercial art market? From galleries to collectors to auction houses, conflicted countries of the Othered have become all the rage. Looking at Christie’s auctions of modern and contemporary Middle Eastern art that take place in Dubai as an example, the confluence of cash and conflict is striking. One has the impression, while sipping on champagne, that the deeper the crisis, the heavier the conflict behind the work, the more the work of art will sell. Working in emerging markets already has its complications, whereby largely Eurocentric investors often take a certain paternalistic approach to investment in new markets. When coupled with the problematic surge of interest by the contemporary art world in work from conflicted countries which also double as emerging markets, we can try and separate the purely economic interests from the Orientalist-based interests of the Eurocentric.

But perhaps things have become so intertwined that it is not about separating them, but rather about trying to understand what this intertwined approach and perspective means for the future of contemporary art from conflicted countries of Asia and the Middle East. Therefore, although the inspiration for these new relational spaces comes from a place of disproportionate power structures and colonialist-rooted attitudes towards the Othered, perhaps they can also become spaces where a radical shift can take place – a shift towards a new era of post-Orientalism, and a new social space of alternative identities and relationships that through contemporary art can move us beyond the cultural legacy of colonial-era mindsets. What might be the possibilities if there developed a true ‘Third Space’ which, as a discourse of dissent, has been presented as taking two forms, ‘one is that space where the oppressed plot their liberation: the whispering corners of the tavern or the bazaar. The other is that space where oppressed and oppressor are both able to come together, free (maybe only momentarily) of oppression itself, embodied in their particularity’ (Bhabha 1994).

The notion of ‘Third Space’ as a postcolonial theory on identity and community, largely accredited to Homi K. Bhabha as part of his arguments on ‘hybridity’ and discussions on where culture might actually be ‘located’, attempts to explain the uniqueness of each person beyond the colonial-era, Orientalist ‘lumpings’ of entire peoples and places into a form of exotic homogeneity. It can also be seen as rooted in the early works of Henri Lefebvre seen earlier in this chapter in his discussions on the production of space, particularly his ideas that influenced contemporary discussions on the notion of spatial justice and equality of representation within spatial realms. It is therefore the second form within the Bhabha quote above that contributes to the potential these new relational structures might provide for the various individuals and institutions involved. In his seminal work The Location of Culture, Bhabha further defines the modality of a Third Space as part of a postcolonial condition where there exists ‘unequal and uneven forces of cultural representation’ (Bhabha 1994).

It is this inequality of representation that concerns us here. For just as the notion of a Third Space could contribute to a certain form of liberation by Othered artists of conflicted countries in Asia and the Middle East from the disproportionate power structures at play, it may even further provide a platform through which a sort of post-Orientalism can be attained. But what would post-Orientalism look like? How could these relationships become more egalitarian? A major obstacle is the idea itself of a ‘post’ anything. When we talk about postcolonial, we imply that the legacies and attitudes of the colonial era are now behind us. But unfortunately this is not the case, and it is much like calling Afghanistan ‘post-conflict’ (which it is more often than not in reference to ‘post-conflict development’) when a conflict both domestic and international is still going strong throughout the country.

(continue reading here)