Scene One: London Soho and Bloomsbury

I used to love London for its Indian and Thai vegan restaurants, vibrant queer cafes, independent bookstores, second hand antiquaries, esoteric health shops, political protests and pickets; for its breath-taking diversity of life, for the vast richness of cultural, sexual and class diversity in Brixton, Islington, Camden… In January 2014, I was walking around Soho and Bloomsbury, two years since my last visit to the city. To my surprise and shock, many of my favourite shops or cafes had been replaced by Starbucks, Pret A Manger, Costa Coffee, Ito Sushi, again and again, in every city centre block, at every 300 meters. What has happened, why have metropolitan cities become so standardized, so boring?

I understood that this is what gentrification means – it stands for the homogenization and ‘insipidifying’ of the urban centres in the name of “hip” and “cool”. This development is doing something irredeemable not only to our cities but also to our minds, our mentality, our communities, and to our understanding of politics. Sarah Schulman, a US cultural critique, artist and queer activist, refers to this development as “the gentrification of the mind”. Schulman claims that there is

“something inherently stupid about gentrified thinking. It’s a dumbing down and smoothing over of what people are and actually like. Gentrification reshapes people’s understanding of the urban experience, and the mind itself becomes gentrified.”

Schulman describes how gentrification took place in New York East Village in the late 1980s and 1990s, coinciding with the many gay deaths of AIDS: The Orchidia, originally a small non-chain food joint run by immigrant Ukrainians and Italians, was replaced by a Steve’s Ice Cream chain, and then Starbucks. At the same time, an Asian fish store was replaced by an upscale restaurant, the Polish butcher by a suburban bar, the dry cleaner by a restaurant, the Dominican tailor by a gourmet take-out store, the corner bodega by an upscale deli selling “Fiji Water”, and a small falafel stand by a “Mexican” restaurant. Meanwhile, rents went from $205 dollars to $2,800 dollars per month as the flats of hundreds of dead gay men went on the market since their partners had no inheritance rights and could not, in most cases, afford to live in these newly-priced flats. The new square East Village businesses were “culturally bland, parasitic and very American”, the opposite of “cool and hip” as they wanted to code themselves – in fact, they were “corporate and destructive of cultural complexity”, writes Schulman.

On the large scale, “gentrification is the removal of the dynamic mix that defines urbanity — the familiar interaction of different kinds of people creating ideas together”. A similar kind of removal seems to be happening in London at the moment, with increasing speed. I am afraid that my experience of the new boring London – caused by the invasion of a few global chains in the central areas of the city – will be increasingly repeated in the near future in Helsinki, the capital of Finland and my home town.

Scene Two: Helsinki City Centre

One of the first symptoms of a new kind of global corporate destruction of the diversity and richness of the texture of the urban culture in Helsinki is the recent introduction of Starbucks – the biggest global coffee chain in the world. If the first cafes in Helsinki prove to be successful, it will expand its grip on the city centre and quite literally eat other cafés and local small shops. This will, presumably, be followed by higher, non-payable rents on shop premises for other than global chain businesses.

The first city Starbucks café in Helsinki was opened in November 2013, in the city centre. Earlier, in 2012, a number of Starbucks joints were opened at Helsinki-Vantaa Airport. Even though I do not count them here as “urban” they do constitute a crucial first phase in the marketing tactics of the brand: placing the first outlet at the airport, in the middle of the “international” buzz at the major entrance to the country creates a horizon of expectation which guides the visitor to expect to find more Starbucks cafes in the city centre. The store decor of every Starbucks café shop is similar, if not identical, all over the world. The visitor is thus made to feel “safe” immediately on entering the country, in the experience of something familiar and standard in the otherwise perhaps strange environment and culture surrounding her/him. This same strategy has been used as the overall tactics of Starbucks in entering the Nordic market – in Sweden, for example, where the first Swedish Starbucks was opened in 2010 at Arlanda Airport. After the airport business location and the first business joint in the city centre, more outlets are opening at a distance of a few hundred yards from each other, thus slowly expanding the chain from the centre along its profitable frontiers while taking over independently run businesses. This will continue even to the point of situating Starbucks shops across the street from one another, as I witnessed had happened in London.

The first city centre business location of Starbucks Helsinki is the most prominent site one can imagine in Helsinki. It is at the street-level floor of the most acclaimed, historical bookstore in Helsinki, the Akateeminen kirjakauppa – literally translating to ‘The Academic Bookshop’. Its large corner windows face Esplanade Park, the Swedish Theatre and the historical department store of Stockmann. Thousands of people pass it every day, not only the busy residents of Helsinki who work in the city centre offices and shops, and the university students from the nearby central campus, but also a vast number of tourists who come to do their shopping in the expensive international design boutiques in the immediate neighbourhood.

A visitor can therefore have the “same” shopping and coffee experience in different “exciting” cities, whether Beograd, Warsaw, Helsinki or London.

In the central Helsinki bookshop outlet, however, the majority of customers seem to consist of girls in the 14-18-year age group, with schoolchildren from 7-11 also spending after-school time there, according to my brief observations on the spot. This very young clientele might be mobilized by a sort of “candy economics”– Starbucks offers coffee with toffee and caramel flavours and hot chocolate with whipped cream. The prices are quite high, but not overtly so. Still, for the average teenager’s budget the coffee is expensive.

Just a few months later, in March 2014, a second Starbucks was opened at the Helsinki city centre student café premises only some hundred meters from the first urban Starbucks. Even though this second Starbucks is merely an automatic coffee machine located in the corner of the student café, it closely follows the marketing tactics of the brand. The Starbucks chain has spread into more than 60 countries since it was established 1971 in Seattle. In 2013, the chain had more than 20,000 cafés of which about 65% were located in the US. Aggressive expansion started at the beginning of the 1990s – which is the golden era of gentrification in the US, according to Sarah Schulman. In the US, the brand has been known for its low-salary policy and exploitation of young workers, and its deep hostility towards trade unions. It is very rare for one to see promotions or job opening advertisements for Starbucks in any typical advertising campaign. The brand uses the marketing strategy of “word-of-mouth” advertising. In Europe, it has been making capital by its clever tax avoidance politics: in the UK, according to Reuters, it did not pay any tax on its 1.5 million pound turnover between 2009 and 2012.

Starkbucks thus contributes to the exploitation of low-paid workers vis-à-vis its transferring local profits to its global ownership, which opposes all kinds of trade union organizations at the national level. In light of this, a group of leftist Finnish students demonstrated their opposition to the business decision on the part of a Unicafe restaurant to host the Helsinki expansion of such an unethical and colonizing chain– but to no avail. However, the Starbucks coffee machine at the student restaurant location was totally ignored during one Wednesday afternoon when I paid a visit there to check the popularity of this new business site. Maybe – hopefully! – the student clientele opposes the new Starbucks automatics policy which does not need paid workers at all: a clever turn from low-salary to non-salary.

Scene Three: Former Working-Class Urban Districts

Not only is the Helsinki city centre under the threat of increasing gentrification via the introduction of the first Starbucks cafés: the district of Kallio, a former working-class neighbourhood one kilometre north of the city centre and divided from it by a “Long Bridge” (Pitkäsilta), is also facing the consequences of gentrification – but in a different way. During the course of the late 1980s and early 1990s, a growing number of lesbians, gays, trans*, students, non-institutionalized artists and other sexually adventurous, politically interested and/or socially and economically marginalized people started to share the flats and streets of Kallio with the older tenants from the previous working-class era. The district has since been known for its low-budget ethnic shops and pizzerias, cheap take-aways and other food places run by non-white individual owners (often Asian families), small queer bars and pubs, independent drinking joints for a bohemian clientele, and numerous Thai massage parlours. My intent is not, in what follows, to romanticise this variety as simply and inherently “good” but to complicate the gentrificating mind’s understanding of “nice”. For example, sex work might be seen by some as a mark of consumerist capitalism par excellence but arguably it has also been a viable option for many paperless or illegal refugees, non-Finnish speaking immigrants, single parents or otherwise socially marginalized people which afforded them a living in an economic system which wants to wipe them from the scene. Kallio has offered space for this during the last two decades.

That is, until approximately five years ago, when the co-called hipsters and other middle-class professional +30 year-old people discovered the Kallio district. They started to buy the small flats at the same time as an assortment of new upscale cafés, galleries and architect’s offices started to replace the diverse, low-cost, sometimes rough businesses. In due course, in December 2013, the only bar specifically catering to lesbians and a historical landmark in Kallio since 1991, was replaced by a “hip” interior-design-sort-of-drinking-spot for a straight clientele. A number of other small pubs where older working-class men, students, bohemians, and queers of all ages and genders used to drink cheap beer have been replaced by expensive brunch cafes, artisan shops and second-hand retro-vintage design boutiques populated by the well-off, heterosexual, white, politically-conforming newcomers. Lesbian, non-scene gay men, non-institutionalized artists, retired working class people, students coming from non-wealthy families and other socially marginalized people are finding it harder and harder to live in the area as the rents are skyrocketing at the same time as the purchase prices for flats have doubled over the last ten years.

One of the symptoms of this homogenization of the formerly multisexual and multi-class Kallio, I will claim, is the recent appearance of “street-gastro”, “city village” and “pop-up” culture. The really rough pub facing my house was recently replaced by “cute” cake and brunch cafés, the pub next to it by a local organic produce shop (really expensive), and the former barber shop premises in my building was replaced by a “sweet” retro-vintage shop. All these “nice” places remove the dynamic mix that used to define Kallio: the interaction of really different kinds of people who created the unique community of the district.

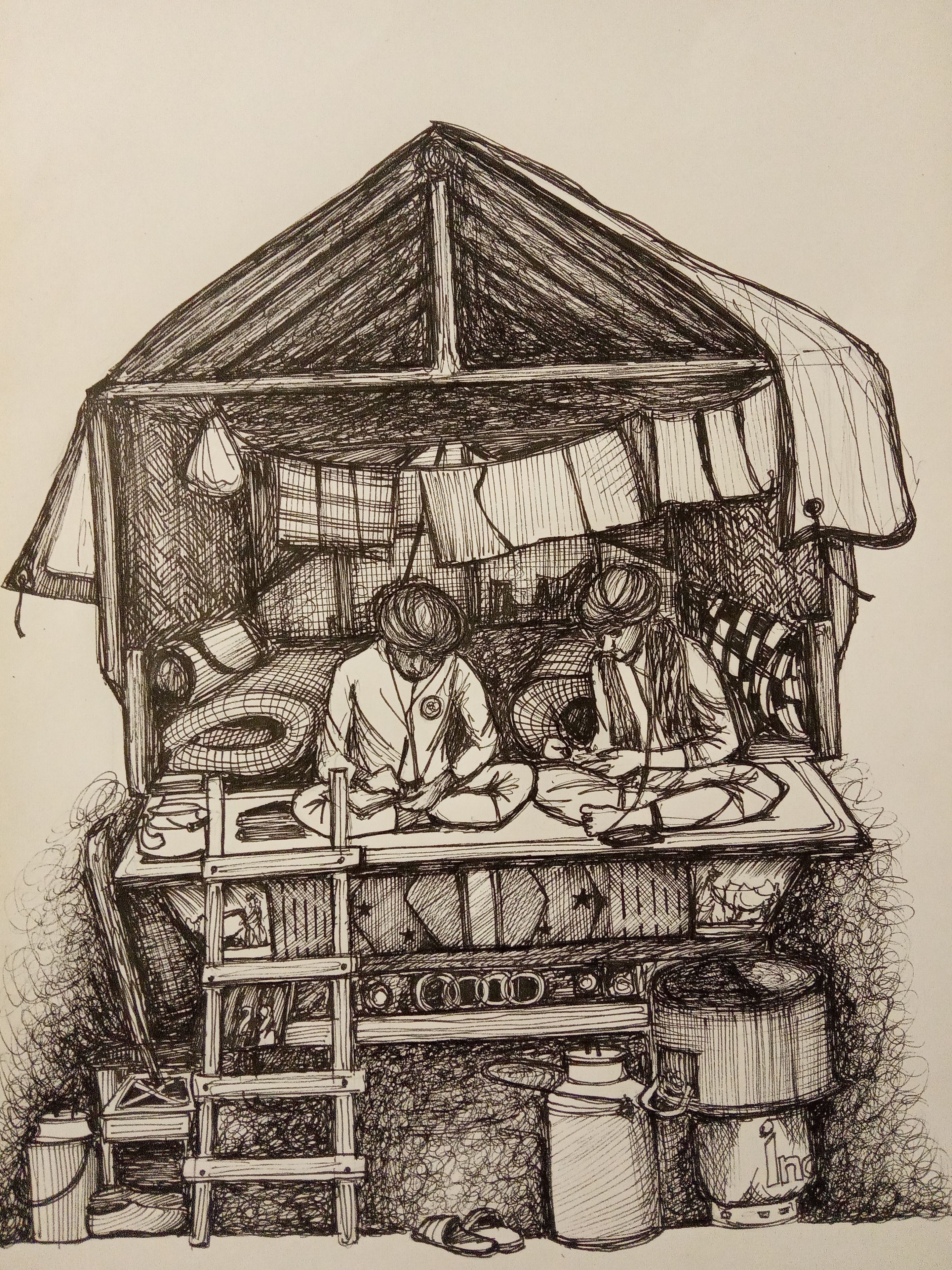

This winter, one of the cheap Chinese take-aways in Kallio was replaced by a pop-up gastro bar which sells gourmet kebabs for a high price and is packed by well-earning professionals who find the “rough” environment interesting but do not want to experience it in its authentic form. These new businesses bask in interior designs that refer to deracinated aesthetics at the same time as they reject more original ethnic cooking and cooks. As Sarah Schulman writes, for the gentrificating mind, eating food “from ‘other’ cultures means going to businesses where people from those ethnicities were both the bosses and the other customers.” The new pop-up “street gastro” does not come with a street-affordable price nor does it come with non-white owners.

This replacement cuisine sets in motion new middle-class fantasy perceptions of “other” satisfactions, spiced or differently spiced foods, “traditional” customs or “street-wise” eating habits which, in their more authentic forms, are conveniently rejected as obscene, low-class or “cheap”, as James Penney has noted.

Another example of the scene of gentrification in Kallio is a “street gastro” opened and run by some Michelin-level cooks from the city centre restaurants – it replaced a small strip-tease business. It is of no small importance that the gentrification of urban space always also means the homogenization of the public display of sexualities. Non-commercial queers and shameful heterosexuals (pornography, open sex trade) are ultimately wiped out from the “nice” city village as hipsters often bring children with them and then claim that the kids need to be “safe”. Even many of those places that have been in the district for some time tend to get homogenized along with the new residents: queers, non-whites, non-confirming, non-trendy people start to feel more and more non-welcomed in many “old” places that are adjusting to the hipster culture clientele. Unlike the earlier mixed Kallio generation (since the late 1980s), who promoted and practiced diversity and political resistance, the newcomers seem to believe that things are better than they are, that they are doing a service for the community by offering all these “nice” things. What is worrying is the fact that cultural memory is very short – they do not seem to be aware of what they replacing, of what they are destroying by all these niceties in the district. Schulman describes this kind of mentality in terms of people who “look in the mirror and think it’s a window”. What happens is that “the oppressed person’s expression is overwhelmed by the dominant persons’ inflationary self-congratulation about how generous they are”. What is “safe” for these gentrifiers becomes dangerous for the earlier, economically and sexually more diverse inhabitants.

Reflecting its former history as a working-class district, and its more recent history as a multisexual, class-diversified and ethno-business neighbourhood, the political atmosphere of Kallio has made it possible for its residents to reflect on the present as a contingent moment where one needs to first identify what is going on, and then force the people with power to do something other than what they want to do. Some queers in Kallio, as a consequence of their disturbing experiences, have started to practice various acts of “counter-capitalist capitalism”, to obstruct the attacks of gentrification which aim not only to homogenize but also privatize the diversity of their lives. These countering acts can consist, for example, of buying flats in the area and then letting them out to other queers at an affordable price. Others buy bars in the district and then cater for the queer clientele.

A significant number of lesbian families buy flats in the area, too, exactly because of its queer-friendly community – their idea of what is safe for kids is in some respects rather different from the hipster family ideologies. Many queer mothers think that the urbanity, and the diversity of the residents, is what makes Kallio a great place to live for themselves and their children. For example, the openly queer café in the central park of Kallio offers a much more “safe” place for them to socialize outside of the domestic sphere and to meet other queers and families in public than potentially queer-hostile suburban or small town space.

The gentrificating middle-class professionals’ “city village” culture in Kallio relates closely to the metropolitan impulse to inscribe a personal mapping of the city as part of the quest for a distinctive sense of self. However, it enforces itself through the repression of diverse expression and thus often proves to be exclusive practice from the point of view of many “old” residents of the district despite the narrative that it is “good” development. The formerly working-class and multisexual district of Kallio has historically been the central location for urban resistance and protest. It has offered cheap rents, cross-class and cross-sexual feelings of practical comradeship not only for the radically political but also for closeted, poor or non-trendy queer people. Even though some of the entrepreneurs commit deliberate counter-capitalist acts, the current development is shifting the public queer culture, especially public lesbian life, into the sphere of semi-public and semi-visible queer economics. Some bars in the area are popular among the straight middle-class cultural clientele but they also offer a safe space for lesbians and gays. Sometimes it is hard to recognize the queer policy from an external perspective as these pubs look straight though if one is familiar with the local lesbian and gay scene the queer clientele of these bars becomes obvious.

Scene Four: We, The Gentrificators

“City village” culture, which is predominantly white and hard to afford on a low income or social benefits tends to alienate many poor and/or queer residents of Kallio who are deeply aware of the dangers created by the promises of “nicety”. The danger that they see is that new exclusions will be created in the process and queer people will be divided into first and second-class citizens in their own city – those who want and can afford to adjust, and to those who want to opt for more diverse urban life and counter-cultures or just do not have enough money to stay in the district.

In question is also the perseverance and renewing potential and resources of political imagination, self-esteem and memory. All this replacing, homogenizing and standardization, this “smoothing over and pushing out”, as Schulman says, “all of this profoundly affects how we think”. We need to be wary that the scenes of gentrification will not create what we think we feel.

When I submitted my first version to Allegra, the editors asked me to reflect on the following:

“Of course we as international scholars are hardly outside the entire process of gentrification, rather we participate in it ourselves as we move in between cities and countries as scholars. As merely one example, being able to rent for 7 months 2 rooms for 1,400 euros in Hackney or a 65m2 flat in central Berlin through air.bnb is part of the gentrification system…so Starbucks is really not the only ‘bad guy’ in the story, even though it is the most visible. Thus, is our anger toward Starbucks an easy target via which to express a more profound upset at certain widespread tendencies of the contemporary era?”

Allow me to conclude my piece by first highlighting the importance of picking on Starbucks as one of major gentrificators and then by touching the issue of the wider tendencies of our era.

Gentrification does not just “happen” to our cities – someone is doing it very consciously, basing their actions on a certain ideology of which we should be cautious – even though we personally might also “benefit” from some of the possibilities and commodities that it is offering to the privileged ones.

It is not an overestimation to argue that Starbucks has greatly impacted the physical and ideological landscape of America and thus holds a unique place in society. According to Susan E. Kelly, Starbucks introduced specialty coffee to the US and educated customers about it, quite literally creating the lucrative market in America in which it, and other chains, could exist: “Visiting Starbucks cafés is a ‘necessary daily ritual’ for many and people regard it with an irrational level of devotion. People will spend four dollars on a cup of coffee that they could purchase for $1.50 down the street, yet they insist upon spending this premium price.” Starbucks ideology has now consciously been spread to all major cities in Europe. It offers us an alluring consumerist enjoyment that, at the same time, binds us to an extremely cold-hearted market strategy.

In more psychoanalytical terms, I would call this a perfect example of the lure of the ego to defend itself against the inevitability of perfect satisfaction by investing in commodity’s seduction, premised on the individualized service and the smooth functioning of the supreme efficiency of the promise of “the American Way of Life” in the Starbucks commercial and universalizing design.

In the US, Starbucks, side by side with some other major chains in other marketing fields, particularly the foodstore chain Wal-Mart and the bookstore chain Barnes and Nobles, are often mentioned as the pioneering giants in destroying the rich diversity of individually owned shops, bars, cafes and food joints, feminist/lesbian and gay presses and other non-multi-billion city industry. These giants have now replaced a vast number of non-profit, small-scale and alternative businesses that have developed a form of urban life controlled by the community itself over the last four decades, rather than by global business rules that target profit, standardization and similitude. Therefore, Starbucks can thus be singularly picked out, blamed and warned about. Organizations such as air.bnb, and cheap flight and bus companies allow some of us to travel more, providing us this nice feeling of freedom and mondial connection, while, at the same time, they making us agree with, and participate in, a value system that has killed so many countercultural business sites, presses, bookstores, gathering places, expressions, imaginings and conversations which fed our intellectual work, as Schulman has described.

We are all socialized and partly constructed by our own era. When the “ontological centrality of the working class” reached a crisis, new social movements developed and diversified our urban landscapes in the “West” post-1960s. New civil rights movements were shaped by the ideologies of liberal individualism and self-invention which gave rise to social formations anchored in ethnic and other identities, as James Penney has noted. Lesbian, gay and feminist movements reflected a political field shaped by these ideologies. What happened in many metropolitan, formerly working-class districts was the invasion of these new diversity “identities” in the form of queer bars, alternative press, book cafés and ethnic shops. This development took place in Helsinki, in the Kallio neigbourhood, in the early 1990s as I have shown in my earlier research.

The topic here is not to fetishize this historical momentum of the visibility of “diversity” but to stress that there is nothing “natural” in gentrification in terms of the development of urban space.

The emergence of the urban visibility of different political “we’s” took place post-1968 but the increased profile of public sites catering for non-heterosexual sexualities coincided and peaked in the 1980s and early 1990s with the collapse of the Eastern bloc, the broad discrediting of the Marxian ideology and the negative societal response to AIDS. Alison Bechdel has “documented”, in her comics The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For, how Barnes and Nobles overran one lesbian bookstore in New York after the mid-90s, at the same time as Starbucks and other gentrificators started to price small enterprises out of existence and thus standardize the city image. Barnes and Nobles itself was in turn outsold by Amazon.com which, famously, removed lesbian and gay topics from its best-seller ranking system in 2009, as “erotic and pornographic books”. Here, gentrification was extended to virtual space where it claimed that there is no need to distinguish between the sexually explicit and the politically necessary. This was not an anomaly, but an example of the gentrification of the mind in the authorial universe, as Schulman argues.

In Bechdel’s comics, it is illustratively described how the lesbian community – a particular fictional group of friends gathering around a certain lesbian bookshop which offered not only a social and political place but also a living for some of the group – gentrified itself by investing increasingly in middle-class family values, “normal jobs” offered by the gentrifying businesses, and in mortgages at “better” neighbourhoods as their rented commune houses were sold to speculators and up-scalers. “Better” always means that we create an idea that there is someone/something we think of as less of value and that we give up the idea of ourselves as a community and replace it with an individuality-based world-view.

The critique of gentrification is often countered by the claim that cities must “go on” and that everything that happens now is just as “natural” a development as was the introduction of ethnic restaurants and queer cafés in former working-class districts in the 1980s and early 1990s. The same districts that are now post-gentrified – East Village in NYC, Islington in London – or are under the process of gentrification – Kallio in Helsinki – were partly created as workers’ communities’ self-building projects in the early 1900s. What happened post-1960s was part of a profound social and economical process, a transition from one society to another where political formations and social identities created during the industrial era were replaced by new social identities and economics constructed through post-industrial socio-economic developments.

As we express our wish that urban places would stay “authentic” and “original” as we saw them, we easily engage in a sort of non-historical nostalgia in which the time-span of our horizon concerning our cities is as long as our own short-lived lives. But then again, the scenes of gentrification discussed above differ profoundly from the earlier developments in urban political formations.

The power to influence the urban scene is increasingly not in the hands of the community, state or even local speculators but the global businesses with universalizing marketing ideologies which ultimately aim to hygienize our lives, not only aesthetically but also politically and socially. As we saw in the case of Amazon.com, this “nice” standardized scene often proves profoundly dangerous to many social and sexual groups.

Gentrification as a concept refers to the historic era of urban replacement. The term was coined in 1964 by the British sociologist Ruth Glass, to denote the influx of middle-class people to cities and neighbourhoods, displacing the lower-class worker residents; the example was London and its working-class districts, such as Islington. (Schulman 2012, 24.)

*********************************************************************

Further reading:

Barale, Michèle Aina. 2000. “Queer Urbanities: A Walk on the Wild Side”. In Queer Diasporas, editors Cindy Patton and Benigno Sánchez-Eppler. Durham: Duke University Press, 204-214.

Dart, Gregory. 2010. “Daydreaming”. In Restless Cities, editors Matthew Beaumont and Gregory Dart. London, New York: Verso, 79-97.

Kelly, Susan E. 2008. A Heroic Monomyth: Howard Schultz’s Narrative Construction of Starbucks.

Penney, James. 2014. After Queer Theory. The Limits of Sexual Politics. London: Pluto Press.

Schulman, Sarah. 2012. The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Simmel, Georg. 1950. “The Metropolis and Mental Life”. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, editor Kurt Wolff. Glencoe, Illinois: Free Press.

Sorainen, Antu and Arto Kallioniemi. 2006. “Multisexual Kallio: A Queer Social History of One Neighborhood in Helsinki”. Yearbook for the Finnish Society of Social Pedagogy 6/2006, 105-114.

Sorainen, Antu. 2014a. “Two cities of Helsinki? One liberally gay and one

practically queer?”. In Queer Cities, Queer Cultures: Europe Post 1945, editors Matt Cook and Jennifer Evans. London: Continuum (in print).

Sorainen, Antu. 2014b. “Queer Care Relations and Personal Lives in a Small Place”. Lambda Nordica 1/2014 (forthcoming).

Featured image: Scott Beale / Laughing Squid (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This post was first published on 1 May 2014.