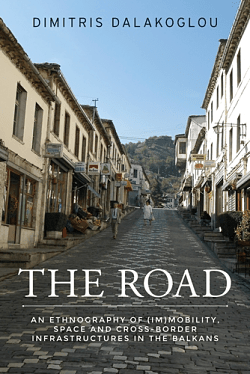

Central to the capturing cover-image, the downhill stone-paved street of the Pazari district of Gjirokastër, south Albania, reflects the orientation of Dimitris Dalakoglou’s book The Road: An Ethnography of (Im) Mobility, Space, and Cross-border Infrastructures in the Balkans in that it places infrastructures at the foreground of understanding sociopolitical processes of change. Drawing from fieldwork between 2005-2006, Dalakoglou focuses on the main Albania-Greece highway and material entities such as the road, the city, and the house to approach post-Cold war Europe through one of its most ‘othered’ and understudied countries. The research participants’ inclination to narrate their socialist past and post-socialist present through the cross-border highway informs Dalakoglou’s consideration of the road beyond a subject of ethnographic inquiry to an integral part of local (hi)stories, perceptions and ontologies, necessitating an anthropology of the road.

It is the ontological diversity of roads, their material, political and sociocultural dimensions with which Dalakoglou’s anthropology of the road is concerned, while employing the Lefebvrian, post-structural perception of space as a process and Latour and Heidegger’s orientations to frame the multiplicity of both tangible and imaginary experiences and realities attached to roads.

Löfgren’s concept of ‘imagineering’ and the ‘road mythographies’ of Masquilier strengthen this framework, which follows an ethnographic genre throughout the book.

Chapter two sets the scene for the main research site: the city of Gjirokastër, south Albania, and the 29-kilometer highway extending from the city to the cross-border passage of Kakavijë. A rich background discussion on this site stretches from Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman times to the World Wars and the Interwar period, the anti-fascist resistance and the foundation of the Communist Party of Albania, the 1944 establishment of the socialist regime, Hoxha’s shifting socialist alliances, Albanian-Greek relations and the 1985 official opening of the Kakavijë border, and the 1997 collapse of pyramid schemes. Highlights include the socio-economic modernization programmes of the 1925-39 dictatorship (with Mussolini’s-Italy construction input) and the socialist regime. The post-socialist period is introduced through the construction boom, the passing of infrastructures from the state to the private sector, and the EU neoliberalist agenda toward Eastern European countries.

Chapter three draws from socialist Albania’s modernization and urbanization programme, focusing on road and house construction. The implications of road-building during state socialism are analysed through the emergent modernization, nation-state, and Albanian socialist subjects. Rich and evocative, interlocutors’ words picture a collective socialist past, often seen as providing (infrastructural) ‘order’, as opposed to the ‘evil’ freedom of capitalism. Individuals’ identification with the road (‘I built this road’, as interlocutors put it) strongly inform their narratives, even though the roads to which they refer were reconstructed after state socialism. Dalakoglou also considers socialist road-construction as an alienating project, while speaking of ‘fragmented’ road identifications for most Albanians who had to construct roads they could not actually use. Importantly, the idea of ‘voluntary’ road-building is discussed through a critical approach to the official history, revealing the shift from voluntary work to a ‘standard measure for social oppression’ (40).

Gjirokastër’s main boulevard in the late 1970s, where the city was expanded during socialism. Source: http://roadethnography.weebly.com/

Gjirokastër’s main boulevard today, where the city expands during postsocialism. Source: http://roadethnography.weebly.com/

In chapter four, the main parts of the city of Gjirokastër emerge as signifiers of three different periods: the pre-WWII old town; the urban complex of the socialist period; and the post-socialist section. The relocation of the urban centre from the Pazari to the 1-kilometer asphalt boulevard represents the transition from the socialist past to the post-socialist present. Being the city’s main link with the cross-border highway and located between the socialist and post-socialist urban sectors, the boulevard constitutes an element of both continuity and transition. The new centrality of the boulevard is discussed as an architectural reflection of the post-socialist emphasis on automobility and migration, which, along with broader construction transformations, intertwines with a change of social practices and perceptions, including the decline of social solidarity, feelings of nostalgia, new local hierarchies, social classes and tensions. The ethnography reveals distinct materialities and experiences emerging from Gjirokastër’s new centrality, picturing broader transitions in post-socialist Albania.

Chapter five moves from the city to a discussion on the cross-border highway. Individual narratives and collective stories ascribe responsibility about accidents, violence and criminally to the road itself. Through people and media’s representations the road emerges as a dark place, frequently accommodating the ‘evil’ as it manifests itself in the political turbulence and armed forces of Albania’s post-socialist history. Dalakoglou examines road mythographies beyond geopolitical and historical divides, by tracing stories of road and danger in the Balkan folklore and road narratives in biblical mythologies and US fiction. Significantly, he shows how the association of highways with modernization in and beyond Albania invites a dual perception of roads as places of ‘ease and progress’ and ‘fear and danger’ (93). Often challenging official histories, the road narratives explored in this chapter reveal local stories, concentrating on car accidents, the events of 1997 and criminal activity along the 29-kilometer highway. They ultimately stress the inseparability of the road from shared experience, memory and representation of the socialist-post-socialist divide.

One of the largest Greek public works companies constructing a road in Gjirokastër. Source: http://roadethnography.weebly.com/

Chapter six follows with two road myths, accompanied by evocative excerpts of interviews. For Dalakoglou, the ethnographic significance of these stories rests in that they reflect common interpretations of an emerging Balkan nationalism, neoliberal globalization from above, and transnationalism from below through the everyday life of Albanian migrants. Designed and constructed by Greek companies while supported by EU funds, the cross-border highway project of 1997-2001 echoes a neoliberal market, contrasting with the socialist construction-ethos. People’s identification with the road has become much more complex in post-socialist Albania. While perceived as an extension of Greece and facilitator of Greekness over the Albanian landscape, the highway also reveals less ‘fragmented’ road-identifications in that it accommodates the massive flows of people and products to and from Greece respectively, an aftermath of the political instability and financial dependency of post-socialist Albania.

Engaging ethnographic narratives disclose the shift from socialist anti-migration propaganda to the poverty generating migration, the material objects migrating from Greece to Albania, and the range of illegal activities involving border-crossing within the problematic context of EU border-crossing legislation.

Moreover, these narratives respond to why focusing on the transition from a xenophobic to an open-border Albania may be more crucial than that of the socialist-capitalist divide. Dalakoglou employs the term ‘road poetics’ to frame not only people’s narrations but also practices on and perceptions of the highway: these invite a social construction of the road that empowers people and creates a ‘local road-related history’ (131).

The last ethnographic chapter focuses on house making which, like the road and the city, presents shifting identifications along the socialist-post-socialist divide. People’s identification with the distinct materiality of the house is a source of symbolic empowerment, the house being built and used by people themselves as a secure financial investment in post-socialist Albania. Like ‘road poetics’, the concept of ‘house poetics’ is employed here to account for people’s practices and perceptions of house making, which is strikingly distinct from house building in that it denotes a process where alienation is not at stake. ‘Making a house’, a key phrase for Albanian migrants building their houses in Albania while living in Greece, reflects a dynamic process of home making through both absence and presence, allowing for individual agency and extending to the making of self under fluid socioeconomic circumstances. This process extends to the broader post-socialist transformation of Albania; where people perceive their country as being ‘under construction’. Interlocutors recount the hidden procedures of building-material importation from Greece to Albania, the prestige of migrants making their houses in Albania, and the anxious process of house-making, mirroring anxieties of the politico-economic transition from socialism to post-Cold war capitalism. Ultimately, the house is not only the main inflow from Greece to Albania through the cross-border highway but also ‘a continuation of the materiality and ontology of the road itself’ (133).

A door traveling from Greece to Albania on the roof of a car. Source: http://roadethnography.weebly.com/

This is an illuminating ethnography, approachable to diverse academic and wider audiences. Dalakoglou balances a focus on local stories with a critical eye on history and politics, providing an excellent piece of contemporary anthropological thought. His own involvement with the people informing his research appears in strategic discussions: the post-socialist household, unofficial means of transferring money, border-crossing and the inflow of house-construction materials from Greece to Albania, are explored via participant observation in the lives of others. Crucially,

this ethnography shows why, and how, cross-boundary spaces constitute powerful means of understanding the complex shaping and circulation of social practices, and processual challenges to political and economic systems from below.

The focus on borders between marginal countries such as Albania and Greece offers an original approach to the shifting ‘centralities’ and ‘peripheries’ of contemporary Europe and beyond. The book comes with an online companion, providing rich images and maps, an author’s interview on the book, and a promo video with music by the Greek band Villagers of Ioannina City, fusing rock with idioms from the Epirus region and inspiring the visitor’s journey into the Balkans.

Dimitris Dalakoglou. 2017. The Road: An Ethnography of (Im) Mobility, Space, and Cross-border Infrastructures in the Balkans. 224 pp. £19.99. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN: 978-1-5261-0934-7

All images courtesy of the online companion.