In her newest book review for Allegra Lab, Fiona Murphy follows the traces that anthropologist Susan Slyomovics draws between Holocaust reparations and possible reparations for the histories of settler colonialism, advocating for Jewish Israeli reparations to Palestinian Arabs. It is the latter connection which makes this book, and Fiona’s review, a very timely one indeed.

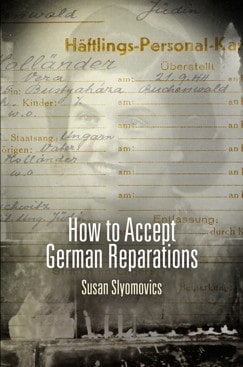

How to Accept German Reparations by Susan Slyomovics, University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 2014 (Hardback)

‘How can we dance when our beds are burning…the time has come to

say fairs fair to pay the rent now to pay our share.’ (Midnight Oil)

A reader would have to peruse many books to find all that one meets in Slyomovics work; it is deeply autobiographical, thorough in its scholarly investigations, and rich with emotion, passion and empathy. It is rare to be able to call an academic book a ‘page turner,’ but Slyomovics ‘intimate ethnography’ achieves this by tracing a deeply moving family history of Holocaust survival to the backdrop of multiple campaigns for Holocaust reparations.

Key to Slyomovics’s investigation are the troubling questions of how in the context of reparation campaigns does one even begin to quantify human suffering, and of course, whose suffering is ultimately deemed valid for reparation.

Slyomovics sets out a critical interpretation of these challenging questions through the lens of her mother’s and grand-mothers’ struggles with the contending forces, even imperatives of Holocaust reparation programmes. The successful interleaving of her mother’s and grandmothers’ narratives with an anthropological reading of reparation is what makes this study so illuminating. Through her family history of Holocaust survival, trauma and suffering; the tangled memories of generational life-worlds wounded and continually haunted by notorious camps such as Auschwitz, Plaszow and Markkleeberg, Slyomovics maps out the qualitatively different, often divisive approaches to reparations of her mother and grandmother. Slyomovics’s mother (until her own mother’s death) vehemently rejected German reparations as a kind of ‘blood money,’ while her grandmother readily accepted them, seeing them as fulfilling a multiplicity of functions, of which revenge partially figured. As such then, the Gordian knot of litigation benights the struggle of those who seek reparations.

While reparations have the potentiality to be healing, Slyomovics carefully articulates how the process of staking one’s claim; sourcing documents, being examined by medics, can also be re-traumatizing.

The dynamic interplay between the voices of Slyomovics’s mother and grandmother in terms of their approach to reparations programmes allows the author to touch off a number of key scholarly topics such as the importance of testimony and bearing witness, and the difficulties and responsibilities of being a direct descendent of a Holocaust survivor. Storytelling, commemoration, and memorialisation in differing forms are tracked as strategies of transformation. Strong communities of Holocaust survivors have grown in cities such as Montreal and Vancouver, thereby creating communities of memory and post-memory which offer freedom but also a version of confinement.

The author also draws upon the confinements and oppressions of the Jewish population living outside of Europe during World War II, particularly Algerian Jews living under the French Vichy regime. It is here that Slyomovics begins to draw out a key argument, that of the underlying relationship between the ‘dark teleology’ of settler colonialism (in its various guises), the Holocaust, and the complexity of repairing for the intersections of these painful histories. While the definition of reparation, then, includes a ‘multiplicity of activities’ and indeed a multiplicity of geographical spaces (Torpey 2006:45), it also intimates towards broader debates such as obligation, respect, relationships and responsibility.

Reparation as such comes to enshrine not solely the pursuance of ‘things’ or objects, but perhaps more saliently, the restoration of mutual respect, relationships, healing, and reconciliation. For Slyomovics, Holocaust reparations are backward-looking past oriented, but reparations for the histories of settler colonialism are future oriented. All forms, however, are ultimately about the project of moral regeneration and reconciliation.

Slyomovics’s book is a compelling one. On a sunny Sunday afternoon, as I sat reading the last chapter (one which makes an important argument about Israel’s responsibility to Palestine), radio news reports detailing the widespread incursions and violence in Gaza played in the background, reinforcing the strength of Slyomovics argument. As the daughter and grand-daughter of Holocaust survivors, Slyomovics embraces a concept of reparation that connects settler colonialism and the Holocaust and thus the multiple responsibilities and forms of justice therein. As such, the last words (redolent with the importance of justice, hope and reconciliation), should indeed be Slyomovics’s:

“Intellectually and emotionally shaped by familial storytelling and filial engagement and despite frameworks of settler colonialism, I advocate for Jewish Israeli reparations to Palestinian Arabs, underpinned by the Palestinian right of return, in order that my Holocaust post-memories may be put in the service of imagining a world, a region, and myself in new ways.” (Slyomovics 2014: 269).

References

Torpey, J. C. 2006 Making Whole What Has Been Smashed: On Reparation Politics. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.