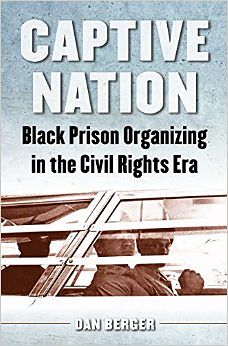

Dan Berger’s relationship with “America’s political prisoners” (xii) has been personal from the very beginning. At age sixteen and out of historical curiosity, Berger sought contact with black prisoners serving lengthy sentences for their implication in the Black Power movement. It is a deeply engaged approach that renders Dan Berger’s Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era a unique contribution to the ever-growing body of prison literature emanating from the U.S. today.

Symbol of Black Power (Image by Joekilil via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Tapping right into the intersection of incarceration, social movements, and racially targeted political economies, Berger’s interest lies in black prison organizing between the late 1950s to the early 1980s. His approach to highlight the perspectives and interrelations of dissident prisoners like George Jackson, Angela Davis, Ruchell Magee, and the San Quentin 6, among others, ultimately allows for their humanization; this is in itself a small revolution as the very project of mass incarceration that took shape in reaction to the prison uprisings that Berger describes depends on the criminalization and thus dehumanization of its mainly black and brown subjects.

Centring his argument on the crucially important figure of George Jackson, Dan Berger composes a tightly woven narrative that convincingly puts the prison and imprisoned intellectuals/intellectual prisoners front and centre of the larger civil rights struggle and discourse. Through meticulously researched primary sources (in the form of personal letters, publications, courtroom appearances and newspaper coverage) Berger eloquently traces the formation of black radicalism inside the prisons and, throughout Captive Nation, follows the personal and intellectual routes and connections on both sides of the prison walls. This extremely rich account starts off by detailing both the civil rights movement’s (chapter 1) and the Black power movement’s (chapter 2) relationship to the prison. Here, Berger traces a significant commonality between the otherwise rather distinct movements: both effectively turned “incarceration from taboo into a resource” (12) to ultimately radicalize the movements and the people behind bars.

The political project of prison organizing –then and now– stresses the salience of slavery as “a permanent feature of black life, less as a regime of labor than as a system of injustice, a form of social alienation and political oppression.” (14)

Chapter 5, “Slavery and Race-Making on Trial,” that hones in on the trials of Ruchell Magee, Angela Davis, and the San Quentin 6 – all of which defendants who had ties to George Jackson – unambiguously establishes the court room as a primary political arena the radical prisoners eloquently navigated. At the same time, here Berger delineates Jackson’s political agenda that evaluated “the currency of slavery as an analytic through which to make sense of imprisonment.”(14)

Not merely critiquing the conditions of their confinement but taking to task confinement and incarceration as a central aspect of the American state and thus essentially criticizing the state itself, black radical prisoners demonstrated the possibility to “enact radical visions and social structures even – or especially – in situations where state power was at its most abusive and restrictive.”(278)

The extraordinary accomplishment of Berger’s book then is to establish unequivocally the prison as a central hub for black radicals: intellectual education, exchange, and movement-building of the civil rights movement and its manifold, often nationalist constituents happen behind bars and largely out of sight.

The prison and the experience of racialized captivity was a rite of passage among civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X and served as recruitment ground for the Black Panthers, Nation of Islam and other radical groups. The prisoners’ accomplishment was to thrust “the prison into public view” and to conceptualize “confinement as a persistent feature of black life woven throughout the American racial landscape” (Berger 4).

Martin Luther King Jr., 1963 via Wikimedia commons

In the epilogue to Captive Nation, Dan Berger crucially notes that American freedom is predicated on state-exerted violence: “violence and freedom have together constituted the American experience.”(268) However, while this kind of American freedom certainly was, and still is, enjoyed by some (white Americans), the violence with which it needs to be thought in tandem is experienced by many others, mostly black and brown Americans. In telling the stories of multifaceted prison rebellions through the narratives of some of their intellectual leaders, Berger sheds light on a time that he considers decisive in shaping the current phenomenon of mass incarceration. Berger’s interest in the prison as “a massive and monstrous classificatory enterprise”(xiv) closely relates to the inextricably entwined, dialectic web of captivity, citizenship, and nationality, a conceptual idea he unfortunately only starts to explicitly develop in the epilogue. The racialization of some populations and, concomitantly, the normalization of others are pivotal to the project that is the United States. However, the fact that black radical prisoners have been able, again and again, to theorize and envision freedom from behind prison walls lets Berger end on a cautiously optimistic note.

According to Berger, the prisoners’ actions demonstrate that “nothing can be taken for granted and that the tragedy of American imprisonment – like the greater tragedy of racial state violence of which it is a part – is neither preordained nor permanent.” (279)

Berger, Dan. 2014. Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era. The University of North Carolina Press. 424 pp. Pb: 34.95$. ISBN: 978-1-4696-2979-7

**********

Featured image: “We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest” by Tony Fischer (flickr, CC BY 2.0)