When I was recently asked to participate in UCL’s Refuge in a Moving World Seminar Series on a panel titled “Forced migration in, through, and from the Middle East”, I found I was unsure about what to say, and whether it was my place to indeed say anything at all. This is often the case when it comes to academic discussions of the so-called “refugee crisis.” On the one hand, I feel this is not “my expertise:” despite having worked for nearly ten years on North African migrations, the particular transnational movement I research is not classified as “forced,” nor are my emigrant interlocutors legally defined as “refugees.” However, on the other hand, while technically not my field of expertise, many elements of the recent “refugee crisis” are extremely familiar to me, as well as to my North African interlocutors: the deaths at sea and the makeshift rescue operations, the rhetoric of invasion and the stories of hope, the defiance of fear and the politics of exclusion and inclusion. While numbers and historical contingencies may be different, for those like me who work on North African migrations, the “refugee crisis” is eerily familiar.

In this piece, I want to briefly address this peculiar resonance between migrations that are legally and socially defined as distinct. In particular, I want to focus on the idea of “forced migration,” and on the fact that there are always complex forces that compel people to move. Placing some forces above others, while at times necessary, generates also paradoxical hierarchies and artificial distinction. While I focus on problems of definition, it goes without saying that definitions have very practical consequences – particularly in the context of migration, where falling in one category instead of another can be a matter of life or death.

Aziz and Youssef

While in Morocco conducting research, I ask a friend why he spends so much of his time planning intricate ways to get into l-barra – a word meaning literally “the outside” in Arabic and used in Morocco to refer to Europe and other desired migrant destinations. Aziz replies:

“My life here is nothing (walu). I wake up and I fall asleep but there is nothing that makes it a life. Ask anyone, they’ll tell you the same: I need to go to the outside so I can live. Here you work like a dog, you study study and study, you bribe like a rich man even if you have nothing…but still you are stuck, still you are not living, you are not moving anywhere, just going round in circles. I’m not stupid. I don’t think there is gold on the street over there, or that people are particularly nice. I know the police beat you up, that even if you have five degrees you’ll be in construction, and that some get so lonely they implode. But in the outside there is always something, there is always the hope that, even if today was really bad, tomorrow will be better.”

Aziz is a young unemployed graduate living in a rural emigrant town of Central Morocco. The town is part of an area that French colonialism coined as Maroc utile, “useful Morocco”, those sections of Morocco that, differently from the regions candidly marked as Maroc inutile, were seen as fertile ground for development and infrastructure. “There isn’t anything utile here”, Youssef, Aziz’s friend, comments bleakly when I ask them whether they know that their land was once considered promising, useful, exploitable. “If you want to do something utile, leave for Europe, as soon as possible.”

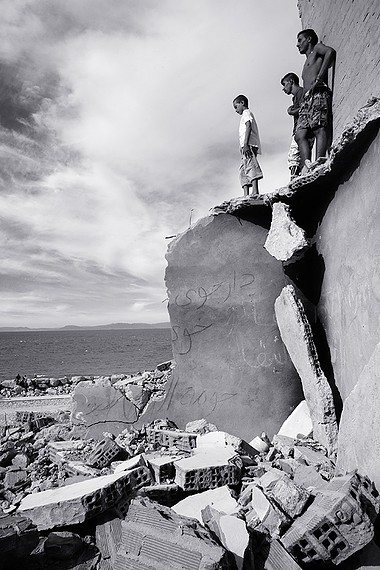

Photo by Leila Aalaoui (published with permission). Leila Alaoui, a distinguished Moroccan-French photographer, was killed in the January 2016 Ouagadougou attack. Thank you Leila for your work of hope. www.leilaalaoui.com

Today, Aziz and Youssef’s town, together with its surrounding rural and mountainous regions, is one of Morocco’s main departure centres for emigration toward Southern Europe. Since the late 1970s, high levels of transnational movement, particularly toward Italy and Spain, have been sweeping the area. Today it is near impossible to encounter a household in the region that does not have at least one family member living abroad. “The rest of us are waiting to join them. You just hold your breath until then – if you survive the wait, that is” Youssef says dryly. As I have shown elsewhere, and as Youssef’s words testify, emigration in this area has affected the very way in which existence, future, and possibility are spoken about and understood, often by younger and older generations alike.

Migration has become for many synonymous with a life worth living, and many of the actions, thoughts, and routines of daily life are infused with a sense of expectation for migratory futures to come.

Moroccan migration, however, does not fall in the category of “forced migration.” Nor are Moroccan individuals who regularly cross, often with deadly consequences, the Mediterranean Sea in an attempt to reach Europe considered, except in extraordinary circumstances, “refugees,” “asylum seekers,” or “trafficked people” – legal and discursive categories that distinguish certain moving subjects from others. From a certain perspective, there are good reasons for this. There is no war currently raging in Morocco. Poverty levels are high, but not outstandingly so. There has been no recent environmental disaster that has displaced vast numbers of people. Indeed, just recently Germany announced, as part of the tightening of its refugee policy, that it was placing Morocco, alongside Tunisia and Algeria, on a list of “safe countries of origin.” For as long as the right to move for non-affluent, non-Western people is accorded on the basis of humanitarian disasters, Moroccans like Aziz and Youssef are not going to fit the bill any time soon. And while it may sound logical that someone escaping, say, a civil war should have precedence over someone who feels stuck in an unliveable life, as always is the case with classifications and distinctions, other problems immediately emerge by thinking this way.

On being forced to move

The International Association for the Study of Forced Migration defines forced migration as “a general term that refers to the movements of refugees and internally displaced people (those displaced by conflicts) as well as people displaced by natural or environmental disasters, chemical or nuclear disasters, famine, or development projects.” As I have said, none of these definitions necessarily apply to my interlocutors in rural central Morocco where I conduct research. However: people aspire to move, sometimes build their lives around moving, and many from this area, denied legal entry by European states, risk their lives in order to reach the opposite shore.

Many, especially young, Moroccans describe their actual or desired migration as something necessary, crucial for their very survival as subjects.

The expression “khassni nemshi,” I have to go, is often uttered in the area, and life without migration is often described as hollowed out, meaningless. This may not be “forced migration” according to the official definition, but the sense of being compelled, indeed forced to move, is palpable. Anthropologists of Morocco have analysed this “force” in different ways. Francesco Vacchiano has written of the ways in which Moroccan children and adolescents who travel unaccompanied to Europe speak of “the burning desire” for migration, so burning it makes them leave family, friends, and home to undertake an often deadly journey. They also speak, as many of my own interlocutors do, of the compelling sense of responsibility toward one’s parents, a responsibility that fuels (forces?) their migratory plans. Similarly, Stefania Pandolfo has shown how disenfranchised Moroccan youths sometimes discuss migration as a religious duty, something that one is required to do when life becomes so unliveable that it parallels a kind of suicide.

How do we distinguish the different, powerful forces that compel people to move? And what are the consequences of imposing a legal distinction between, say, the force of hope and the force of war?

Again, my suggestion is not that these forces are the same – though they do often intimately overlap –, but rather that both forces powerfully compel people to move, incessantly defying the classificatory regimes imposed on them.

The problem lies also in the fact that, as scholars of law and of political theory have always argued, classificatory regimes quickly become reified into categories of being, erasing the artificiality of the categories themselves. Think, for example, of the category “illegal immigrant” – the classification many of my Moroccan interlocutors are given if they survive the perilous crossing into Europe. Time and again we have seen how the category “illegal immigrant” quickly shifts from a formal definition of an individual who does not own the correct documentation for a specific legal regime in a specific time and place, to a description of the very quality – even moral fibre – of a person. Many have argued that a similar process of moral classification is taking place with the recent “refugee crisis.”

Nadine El-Enany from Birkbeck School of Law, for example, has recently analysed the distinction between “the migrant” and “the refugee” made in the media portrayal and popular perception of people seeking entry into Europe. She points to how easily we forget that the categories of migrant, asylum seeker, and refugee are “artificial and historically contingent in that they do not represent natural or predefined groups of people, but instead construct them”. She argues that much is to be gained from conflating the categories of refugee and migrant if we are seeking to understand “what these categories signify in actuality, not purely in legal terms. In reality all those moving are migrants: people moving out of a desire to better their existence, whether in flight from extreme poverty or persecution. It is merely that the law grants some of them rights, at least in theory, and others not.” She continues: “the distinction drawn between migrants and refugees is both false and dangerous in reinforcing the idea that some migrants are worthy of humanisation, while others are not.”

Flight

It is vital in the current historical, social, and political moment to interrogate the categories assigned to moving people, as El-Enany and many others are doing (see, e.g., the collective writing project Europe/Crisis: new keywords of the crisis in and of Europe). We have seen how even an apparently straightforward category such as “forced migration” is not as easily distinguishable on the ground as we may expect. However, to conclude with a critical point (and this applies also to my own argument), I think we need to pay close attention to the mode in which we (re)categorise moving people. What is often seen as uniting refugees and migrants is desperation, dispossession, poverty. This is indeed sometimes the case, and in specific socio-political climates it does makes sense to insist on the humanitarian discourse in order to alleviate the strict, and deadly, migration restrictions in place.

However, the risk of focusing on the desperation of people on the move (whether categorised as “refuges” or “migrants”) is that we reiterate the idea that the movement of some should be allowed only in situations of need. One rather simple, and maybe even simplistic, question always bugs me in these cases: why is the desire of young North Africans to cross the Mediterranean so rarely framed as a desire to travel?

Why are words such as curiosity, adventure, experience so rarely heard when we speak of North Africans, and so often used when describing the transnational movement of, say, young Europeans?

In making my point about the problematic definition of forced migration, I have evoked stories of deep existential and social frustration in Morocco, and the underlying sense of hope that fuels the migratory projects of my interlocutors. But this is just part of the story, as always. Many list, next to the burning need to begin a life worth living, also a wish to see Paris, a curiosity to hear people speak English, a desire to visit an old aunt in Italy. Emphasising frustration, desperation, or the need for help, while sometimes effective and sometimes truthful, also reiterates a specific image Europe has of “the other” and of itself, as well as reiterating specific relations of power, hierarchy, and charity. It also reiterates the idea that while “we” may travel for curiosity, indecision about the future, or love, others may travel – and indeed only desire to travel – out of desperation, poverty, fear.

Again, this is sometimes the case. Though we must not forget, as a side note, that migration laws often directly foster this desperation, poverty, and fear. The near impossibility, for example, for a young Moroccan to obtain a visa to enter Europe, which would in turn allow her to board a cheap EasyJet flight from Marrakech Menara Airport rather than pay thousands of pounds to travel on a rickety boat that may take her life, undeniably contributes to the pictures of desperation, poverty, and fear the European media is so fond of.

And while when faced with something like the current Syrian war it is crucial to highlight Europe’s responsibility to respond to such a disastrous historical situation, even in these extreme cases, I doubt the language of desperation is the most effective to capture the complexity of the current human mobility. It definitely wasn’t a few years ago, during an earlier, and more excited stage of what we then called the “Arab Spring”. When young Tunisians started arriving to southern Italy during the Tunisian revolution of 2010/2011, the Italian and international press swiftly adopted a language of crisis. These young men arriving to the Italian island of Lampedusa, we were told, were desperate people escaping from the revolution, they were asylum seekers and maybe even refugees – and, incidentally, they were going to swamp Europe.

However, many of the Tunisians I have spoken to who crossed the Mediterranean at the height of the revolution, tell a very different story. They never mention escaping from a revolution that many instead contributed to precipitate. They never describe their dangerous crossing into Europe as a desperate act. If anything, they speak of a crossing that was made possible by their experience of the revolution, by the courage and defiance they learnt from it. Indeed, migration researcher and writer Gabriele del Grande has put forward the argument that these young Tunisians were instantiating a second rebellion, this time not against Ben Ali regime, but against a border they considered unjust, and against a legal ban on travel to Europe they experienced as claustrophobic.

People move for different reasons, compelled by different personal and historical forces, and with different desires and expectations.

The language of crisis and desperation at times is maybe necessary – though it is worth remembering that, in the UK, this kind of language has produced a dismal acceptance of 20,000 refugees from Syria over a period of five years, hardly a humanitarian revolution. But this language also risks obfuscating what human movement may be about, and also risks reiterating specific categories of existence and relations (e.g., the curious European traveller VS the desperate migrant other) that may foster rather than alleviate what we periodically define as “crisis”.

Featured image by fdecomite (flickr, CC BY 2.0)

“Crisis” and “desperation” can be applied to many Europeans “curious” travellers too