This week we are featuring a series of posts curated by Dimitra Kofti on a very timely theme: CRISES.

Etymologically deriving from the Greek infinitive κρίνειν (krinin), crisis originally meant to formulate an opinion, to decide and to judge. In medical terms, it came also to mean the sudden deterioration of the symptoms of a chronic disease, underlining that each crisis is positioned in longer historical processes and chronic phenomena.

While transformation and change are inherent to societies, crises can be moments or periods of abrupt changes, decisions and ruptures. However, the prolongation of the phenomena of what might be called crisis tend to normalize its experience and may blur the boundaries between normality and crisis.

As Koselleck (2006) has suggested through his study of the genealogy of the concept, one needs to historicize the crisis, as ‘…it has been transformed to fit the uncertainties of whatever might be favored at a given moment’ (ibid:399). Recent studies have turned the attention to ways in which the concept of crisis has been deployed in diverse contexts (Roitman, 2014).

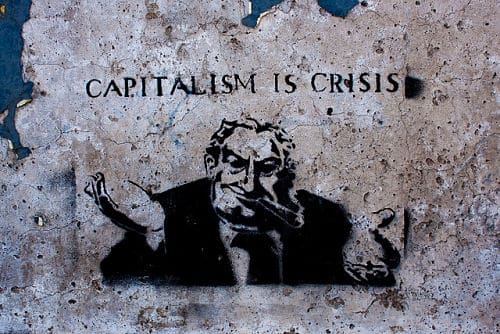

The recent turmoil provides the ground to challenge the current system of market economy. Crisis has been discussed and understood as a systemic ingredient of global capitalism (Harvey, 2010) as it has also generated various social movements of diverse political orientations. Some mobilizations have triggered new ideas about reciprocity, solidarity, social commitment, sacrifice and morality and opened up debates about the vitality of current hegemonic political regimes. However,

crises often result in temporalities of emergency, which provide the ground for rapid political decisions, based on given ideological assumptions that leave little space to challenge conventional ideas and to generate alternative ways to think about politics and the economy.

Constructions of crises provide the grounds for legal interventions as well as for creating new targets of financial speculation, including the commodification of nature and the commons.

The recent economic turmoil, as developed in Southern Europe, has largely legitimized the implementation of austerity measures, the further demise of the welfare state and new practices of precarious work, based on a state of exception and emergency (Athanasiou, 2012). Therefore, a crisis might not only provide the ground for a judgement based on critical thinking, but on critical decisions and directions, bringing to the fore particular issues while silencing others. As Alexandra Bakalaki’s contribution ‘Crisis, gender, time’ shows, although the feminization of poverty and gender inequality has deepened in crisis-ridden Greece, pointing out diversity is often seen as undermining peoples’ solidarity against a more general ‘human’ crisis. She underlines that the more general category of the ‘human’ that struggles for survival becomes more important while talking about gender and other inequalities is often seen as not timely and are therefore neglected as subjects of discussion and intervention.

Photo by SaltGeorge (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The crisis of capitalism calls for an attention on how shifts in political economies entangle with moral economies and vice versa. Jaime Palomera’s contribution ‘Did Main Street become Wall Street? The financialization of social reproduction’ points towards this direction. He suggests an anthropological reading of the Spanish housing crisis and indebtedness, by bringing together global financial institutions, state politics and the household. Similarly, Alice Elliot’s contribution ‘Crisis on the opposite shore’ looks at ways in which the economic crisis in Europe and the revolutionary upheavals in North Africa have shifted the geographies and the imaginations of ‘Europe’ and ‘the West’ as viewed by migrants and their families in North Africa. These new conditions have altered the migratory practices related to access to resources, while they have changed the spectrum of future possibilities. Both Palomera and Elliot conducted fieldwork before and during intense socio-economic shifts related to the recent economic crisis, providing comparative ethnographic material on the transformations occurred in peoples’ livelihoods.

This collection of short articles addresses questions related to the concept of crisis in its socio-historical context, and/or focus on phenomena of the recent global economic crisis; it seeks to generate discussion on the ways in which crisis is discussed, constructed, theorized and hits the ground. Furthermore, it seeks to show the necessity of anthropological analysis in understanding current political and economic transformations.

This necessity triggers questions about the past and the possible future directions of the discipline. James Carrier’s contribution ‘Asking Gramsci’s question’ turns the attention to the crisis of the world economy in relation to a crisis in anthropology. Carrier draws parallels between dominant anthropological orientations of the last three decades and neoclassical economics, arguing that the centrality of the individual in the neoliberal ideology is also reflected in much of the anthropological analysis that has focused on the autonomy of the individual. Therefore, this thematic thread also seeks to open up an endoscopic discussion about the way anthropology may approach these recent phenomena of crises and how anthropological analysis has been affected by them.

References

Athanasiou, Athina. 2012. The Crisis as “State of Emergency”. Athens: Savvalas. (In Greek).

Harvey David. 2010. The Enigma of the Capital and the Crises of Capitalism. London: Profile Books.

Koselleck, Reinhart. 2006. Crisis. Journal of the History of Ideas 67 (2): 357–400.

Roitman, Janet. 2014. Anti-Crisis. London: Duke University Press.