Sitting at an empty table, occasionally sipping from a large white cup, the Russian President Vladimir Putin seemed to be enjoying himself about one hour into the press conference. While he had appeared uneasy and was repeatedly clearing his throat during the first sixty minutes, he became increasingly confident and started joking three hours into the event. With the eyes of the world on Russia, what did he tell his audiences, both global and bodily present?

Leaving aside his placating words on the dramatic decline of the economy, a central point were Putin’s statements to the journalists that it is not Russia that is aggressive, but the West. Conjuring the image of the “Russian bear,” his analogy went as follows:

“And then, when all the teeth and claws are torn out, the bear will be of no use at all. Perhaps they’ll stuff it and that’s all.”

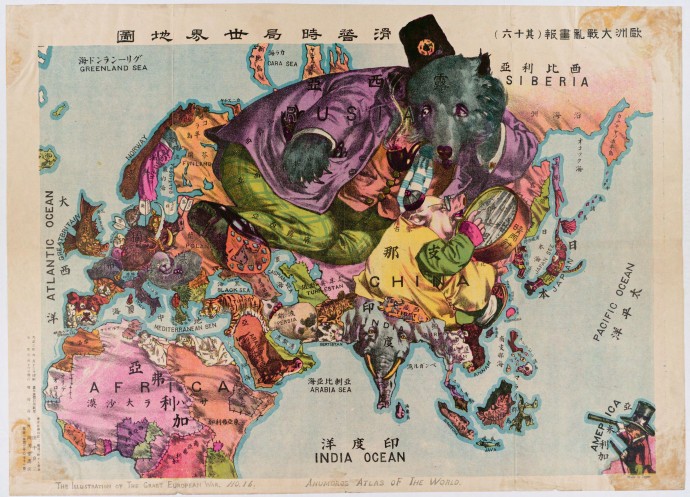

Speaking of stuffed animals: Putin has earned quite a reputation of posing with and domesticating wild animals that led, among others, to Internet memes seeing him riding a large bear. Maybe this was the reason why Russian journalists at the press conference renewed their already established technique of raising not only cardboard signs with the name of their news agency to get their President’s attention, but also plush animals. Next to a crocodile and a pink bunny, bears were among the most visible species in the room. Putin seems to like bears. Exactly a year ago during another major press conference, he interrupted his answer to one journalist’s question in order to take a question from a young woman holding up a gigantic stuffed Yeti: “I want to take a question from the girl with the bear. That looks more interesting.”

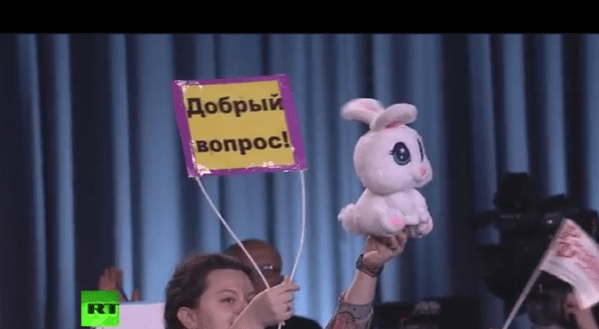

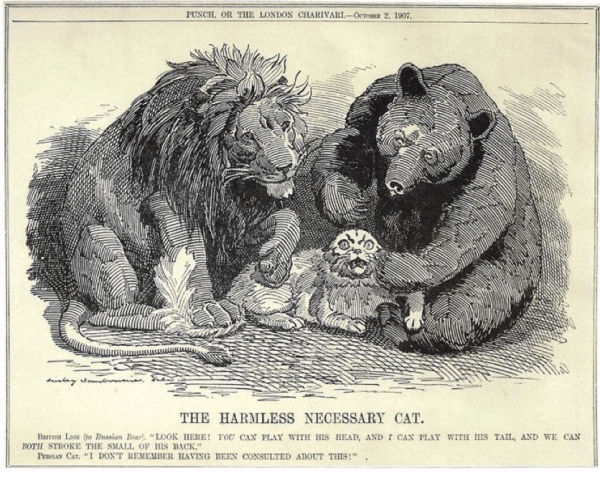

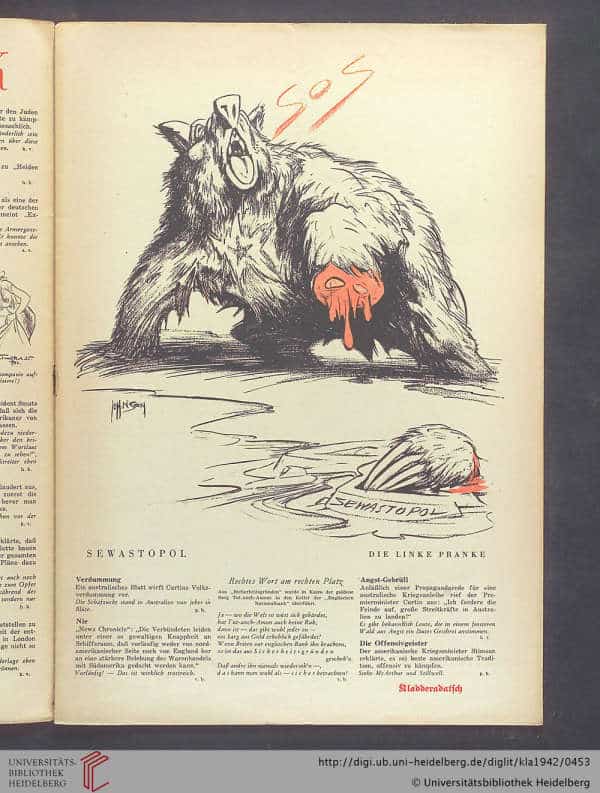

The Russian bear has been employed in political rhetoric, folk stories and satire within Russia as well as abroad from the 17th century onwards. It is one of the most well-known and recognizable symbols of Russian nationalism imbued with positive attributes by Russian authors (as civilized, authentic, strong, and loyal) and with negative features by foreign voices (as savage, cruel, and aggressive). The bear embodies the divided perspective between the “East” and the “West.” While the bear in Russian folk stories had been an “old acquaintance” of the people, with magical powers and charisma, but also easily fooled, it was assigned an aggressive character in the 19th century during the time of the so-called Great Game. There, “the Russian Bear” fought against “the English Lion” over Central Asia.

The imagery remained popular throughout the 20th century, and has since then been particularly associated with the Crimean peninsula over which the White and later the Red Army, and now contemporary Russia exercised influence.

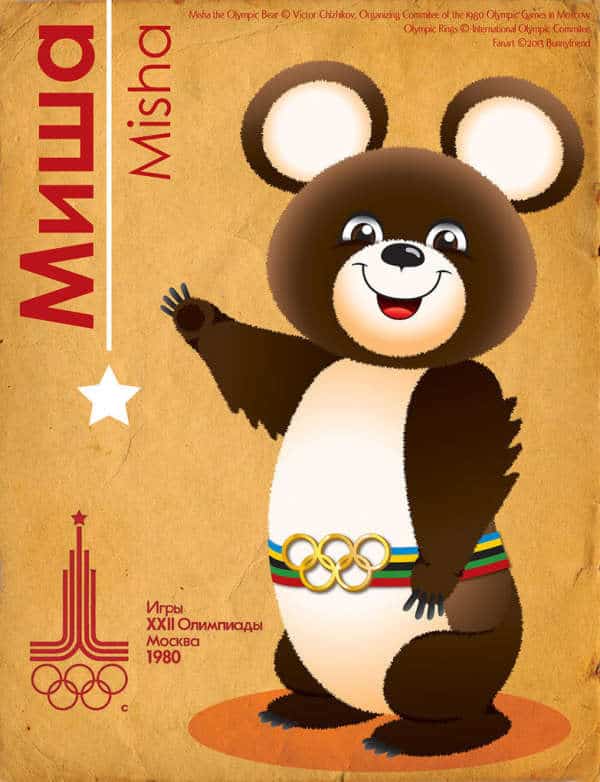

Trying to shed the iconic bear’s negative aspect of aggressiveness, which had been bestowed by “the West”, the USSR tried to domesticate the creature itself in 1980, in an effort to redefine the country’s image. The prime example is brown-furried Mishka, from the 1980 Olympic Winter Games held in Moscow. He was the first broadly advertised Olympic mascot and even got his own animated TV series. Mishka is the diminutive of Mikhail, the name of the bear in the Russian folk tale, while the proper name of the bear is Medved’ (lit. “honey-eater”).

When the Cold War ended, the Russian bear “died”, too. For Ronald Reagan, it had been “sick” for a long time. However, by the late 1990s, the rhetoric of the bear’s “aggressiveness” returned on the occasion of the wars in Chechnya. It has since then remained a part of international public discourse and – in response – provoked the reaction of Russian officials.

Looking at the bear is looking at the body politic of Russia. This has become even more so with the entry of Dmitri Medvedev, the current prime minister. His name being a derivative of “bear,” numerous puns and anecdotes circulate in Russia, particularly about how Putin tamed Medvedev to show that politics is nothing but a circus.

The 1980’s original Mishka bear.

When a polar bear became the mascot of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympic Games, the artist who had designed the Mishka for the 1980 games claimed fraud: “It’s exactly the same as mine: the eyes, the nose, the mouth, the smile, though it’s askew,” he said. “I don’t like it when people steal, the author always feels it especially painfully.” However, the 2014 bear never reached the 1980s’ popularity anyway. It was rather mocked in social media as #nightmarebear with #sochibearproblems. The bear, apparently, was in a state of crisis.

In March 2014, British UKIP leader Nigel Farage warned: “If you poke the Russian bear with a stick he will respond. And if you have neither the means nor the political will to face him down that is very obviously not a good idea.” While in media presentations and political proclamations of “the West” the Russian Bear has remained an aggressive creature, ready to attack once provoked, the image conjured in yesterday’s press conference by both Putin and the journalists attending him was a very different one. At the end of his bear analogy, Putin clarified “So, it is not about Crimea but about us protecting our independence, our sovereignty and our right to exist. That is what we should all realise.” According to Putin, all the bear wants is to be left alone, roam the taiga freely and eat berries and honey.

“Piglets? Taiga? Bears? Berries? What?” asked Nadya Tolokonnikova in a Facebook post on 18 December, not the only one wondering about Putin’s analogy, which, by the evening, had made it already into a YouTube rap version

A founding member of Pussy Riot, Tolokonnikova served a 2-year prison sentence in various labor camps throughout Russia until last year and has since her pardoning by Putin on the occasion of Constitution Day become an even fiercer critic of the President. She thinks the current situation is best understood as a psychological one: “my conclusions are purely formal, my interest – medical: I wonder about his [Putin’s] psychiatric drug treatment or diagnosis.”

Whether one wonders about Putin or Russia in general, perspective is of importance. While the bear has remained, as Putin himself said, “our most recognisable symbol,” what it has come to symbolize is increasingly unclear. Not only Russian activists like Tolokonnikova but also Western observers were bewildered by Putin’s choice of words.

If we stop for a moment, however, and take the analogy serious, what are we seeing? In my view, Putin’s analogy presents an attempt to redefine a country’s image by providing a counter-interpretation of the inevitable bear. If the bear could, Putin said, it would enjoy bees and honey. But immediately, a Western news outlets turned these words around, paraphrasing Putin as having said that the bear “isn’t about to sit back”, thereby again returning to the comfortable image of Russian aggressiveness.

The Russian Bear continues to be different things to different people, and Putin’s attempts to reconfigure this metaphor will not be the end of this perpetual interpretive exercise. The bear won’t go away, either.

But it serves us well to realize that possible alternative frames exist when we talk about what “Russia” wants or needs: both Olympic bears of 1980 and 2014 were seen crying when the Games were over.

Judith Beyer is Reviews Editor at Allegra – follow her on Twitter.

This post was first published on 19 December 2014.