In this post, I outline first findings from my ongoing research project on “Accountability in statelessness.” The project is based on observations from ethnographic fieldwork among expert activists whose work focuses on holding nation states accountable to provide an end to statelessness. I also work with textual data obtained from my work as a country-of-origin expert in asylum cases in the UK, in which individuals are expected to give accounts of themselves in order to prove that they are stateless. Finally, I explore accountability as an anthropological concept in its broadest sense, as well as in the more specific sense of “perpetrator accountability,” taking the case of Southeast Asian Muslim Rohingya as a prime example. In this post, I will show some few ways in which I see accountability being interlinked with statelessness.

Holding the state accountable. The role of expert activists

In my ongoing research project I focus on “expert activists,” as I call them, who have made the nation state their opponent. Their protest ground is located in the centers of power rather than on “the streets”. Their strategies are varied and encompass the organization of conferences and meetings, the public launching of reports in direct vicinity to or within state, EU- or UN- facilities, but also strategic litigation, art projects and the developing of tools for teaching about statelessness. They yield the law, litigation, policy documents, and the writing of reports as their tools of resistance. Any state that has not ratified the two UN conventions on statelessness (from 1954 and 1961), any state that does not adhere to the two legal texts’ proclamations; any state that has no specific statelessness determination procedures in place; or any state that threatens to or has already denaturalized any of its citizens, might become the target of expert activists fighting statelessness. Depending on the organizational set-up, their set tasks and goals might be small, while others are encompassing and some appear utopian. In the words of one representative of a small NGO from Southern Europe that concentrates mainly on strategic litigation: “we first wanted to go against Greece, but we did not have the capacities, so we only went against Albania.” A focus on this kind of experts will provide a new angle within the emerging anthropology of activism.

Among expert activists, statelessness is characterized as an anomaly, something that is not supposed to occur in a world of nation states. And indeed, the UN Refugee Agency wants statelessness to end by 2024. With the launch of their 10-year campaign entitled iBelong in 2014, they engaged a wide network of organizations, experts and activists in their endeavor to fight statelessness and guarantee every individual the right to a nationality. Most expert activists with whom I am currently working concentrate on raising awareness for the need to amend national legislation and put their efforts into helping individuals obtain citizenship or at least secure an official status as being recognized as a stateless person who can claim rights of her own and is worthy of protection. However, it is mostly within nation states that people become de facto stateless first.

Making people stateless, including one’s own citizens, is often an intended side-effect of national engineering, of resizing populations, redrawing borders and trying to keep an upper hand on the question of the ethno-religious majority-minority ratio.

Thus, the reasons why the numbers of stateless people have not decreased in the last decade since the UN has launched its campaign are not only to be sought in the beginnings of new wars (particularly Syria) or mass expulsions as in the case of the Rohingya in Myanmar, but in the very set-up of the nation state itself that will keep on othering unwanted Others in order to reassure itself of its very principles. This paradox makes an anthropological investigation of statelessness particularly interesting as it complicates previous understandings of the relation between state and citizenship. This has been noted in academic work on statelessness (Bloom 2017, Cole 2000), but is rarely heard among expert activists who need to sideline the structural set-up of the nation state they are operating in, in order to be able to operate at all.

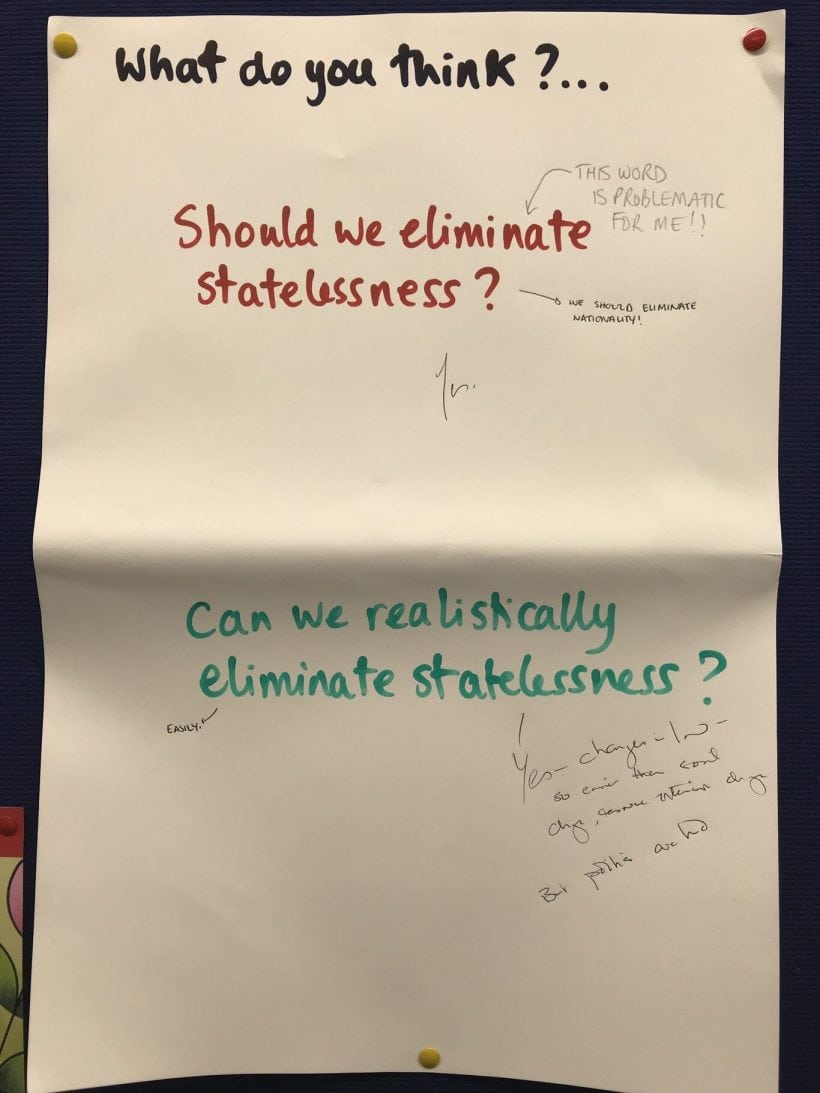

Should we eliminate statelessness? Poster session at a workshop in London, 2017. Photo: Judith Beyer.

Having to give an account of oneself. Proving statelessness in asylum claims

Statelessness can be technically differentiated into de jure and de facto statelessness; while this difference clearly matters, it is not easy to demarcate both. The problem with de facto statelessness lies in the fact that it circumscribes the lived experiences of an individual independently of their actual legal status, and has to cover a lot of quite different phenomena. The problem with de jure statelessness, which is defined in the 1954 Convention as “a person not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law” (Art 1,1), lies with the burden that is put on individuals to account for their status as “stateless” in a court. By having to give accounts of who they “really” are, and being challenged on them every step of the way, individuals who claim to be stateless are in effect being personally made responsible for their own fate: The burden of proof is on them (and their lawyers).

So, while expert activists demand accountability from nation states for their treatment of stateless people, states demand accountability from stateless people. This happens as soon as persons claiming statelessness and seeking asylum come into contact with a nation state, personified by an immigration agent at the border.

Those “first contact encounters” not only reveal how accounts are being co-produced in interaction but also how “culture as fact” is created to be added as “evidence” to the evolving asylum case.

Over the course of an approximately two-hour interview, decision-makers and claimants will become members of an interaction, albeit unequal ones with contradictory goals, one more personal, one more institutional, and each trying to impose a definition of the situation that the other cannot refute. Two things happen in this process: first, they co-create documents (even if antagonistically) that give accounts of their interaction as well as of their positionalities. These documents will later be used in court, thus extending their face-to-face interaction into the future and enlarging the participating audience. Thus, not only is the case of the claimant argued, but the validity of the state’s account of itself is substantiated as well.

According to ethnomethodology, giving accounts “depends on the mastery of ethno-methods” (Giddens 1979: 57; 83; Garfinkel 1967). Even as the actors do not know each other personally, there is still common-sense knowledge and implicit understandings at work in those “first contact encounters”, as I call them. The two interlocutors – the immigration agent and the asylum seeker – engage in a to-and-fro during the interview: One is trying to continuously update their accounts based on what the other person has said or what they imagine the person needs to hear, and the other much more freely switches topics in their efforts to fulfil the parameters of their inquiry. What is unclear, however, is whether actors also work towards establishing a “meaningful social outcome” as is usually assumed in ethnomethodology, since their interests are diametrically opposed: one wanting to stay, the other one having to exercise “the sovereign right to exclude” (Anderson et al. 2011: 549), even when wanting to “help” migrants (what Verkaaik 2010 has called the “cachet dilemma”). Such “document acts” (Smith 2014) keep the shared fantasy of “the state” alive that lies at the core of both modes of reasoning: On the one hand, “the politics of conditional hospitality” (Khosravi 2010) that is exercised by the “host” at the border needs to be understood as an incremental part of nation-building: reconfirming the state’s territory, its populace and its power by “welcoming the other to appropriate for oneself a place and then speak the language of hospitality” (Derrida 1999, 15-16; cited after Khosravi 2011: 126). On the other hand, the stateless asylum seeker has learned that in order to be able to enjoy any rights at all, they will need to become a citizen or an officially recognized stateless person (see also Andersson 2014, 222f.). However, there is no right to citizenship, and thus states can neither be held accountable for failing to “naturalize” those who seek asylum nor are they held accountable for making people stateless themselves.

Perpetrator accountability vs. making the making of statelessness count

Accountability is an essential element in calls for justice: it is what is demanded from war criminals, for example. The UN High Commissioner stated the following after the International Court of Justice (ICC) had released the verdict against Ratko Mladic in Yugoslavia on November 22, 2017: “Today’s verdict is a warning to the perpetrators of such crimes that they will not escape justice, no matter how powerful they may be nor how long it may take. They will be held accountable”. But while war criminals may be held accountable for genocide, they are not explicitly accused of having caused statelessness, even if that is the outcome of their actions. Consider the case of the Rohingya, where statelessness has and continues to impact on the lives of millions. By now, it has been internationally acknowledged that the most recent expulsion of over one million ethnic Rohingya from Myanmar to Bangladesh since 2012 constitutes genocide, and the demand has been made that the atrocities committed by the armed forces should be brought before the ICC. Several times, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya were uprooted from their homes and forced to relocate between the two countries. Neither Myanmar nor Bangladesh have ratified the two UN conventions on statelessness (while having ratified the Genocide Convention already in the 1950s), even as they have been engaged with the issue of how to deal with the Rohingya since the 1970s. Through rejection of the specific legal framework available, they have evaded accountability while giving very specific and partly incommensurable accounts for their actions. Demanding an end to the Rohingya’s current statelessness, while certainly sensible and noble, at the same time misses how the two nation states have operated and how their modes of reasoning continue to build on the British colonial set-up that brought the two nations into being in the first place.

Here’s a provocative thought: would it not help stateless people like the Rohingya a lot more if public debates would not only center on the question whether perpetrators had committed an act of genocide or “merely” a crime against humanity, resulting in a call for justice for those who have been killed; but if one could hold people specifically accountable for making hundreds of thousands stateless in the course of these events?

Statelessness should be understood as an often intended rather than a mere side-effect of other “clearance” operations. The results are not only long-term for those who have to live through times of extreme violence and forced migration, but they impact on future generations as increasingly children are being born into statelessness.

It is important to emphasize that this is not about comparison, or about grading such horrifying offenses. But what if causing statelessness was a prosecutable offence, or at least what if it was publicly acknowledged that statelessness is the result of policies and actions, rather than a natural and unfortunate occurrence? Maybe then, the burden of accountability would no longer be with the stateless but with those who have made them so.

** I thank Luigi Achilli for comments and suggestions.

References

Anderson, Bridget, M. Gibney and E. Paoletti. 2011. ‘Citizenship, deportation and the boundaries of belonging’, Citizenship Studies, 15(5): 547-563.

Andersson, Ruben. 2014. Illegality, Inc. Clandestine migration and the business of bordering Europe. Oakland: University of California Press.

Bloom, Tendayi. 2017. Noncitizenism. Recognizing noncitizen capabilities in a world of citizens. London: Routledge.

Cole, Philip. 2000. Philosophies of exclusion: Liberal political theory and immigration. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1979. Central problems in social theory. Action, structure and contradiction in social analysis. London: Macmillan; Berkeley: University of California Press.

Khosravi, Shahram. 2011. ‘Illegal’ traveller. An auto-ethnography of borders. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Smith, Barry. 2014. Document acts. In: Institutions, emotions, and group agents. Contributions to social ontology, edited by Anita Konzelmann Ziv and Hans Bernhard Schmid, pp.19-31. Dordrecht et al: Springer.

Featured image: “Stateless Immigrants” by Charles Hutchins is licensed under CC BY 2.0