It has been a while since I have last encountered her – I wonder if I will still recognize her. Sure, she could disguise herself, to become instantly unrecognizable if she wanted to, but I have a feeling that this time she wants to be discovered.

She has certainly been leaving traces of herself to suggest as much. Also, although I shouldn’t know this, she has forgone the usual techniques for someone wishing to remain undercover by using her regular credit card instead of that issued for her undercover personality for some of her recent purchases – one of which led me to this pub.

A large pint of lager is what I am looking for, along with a bubbly personality and a compelling smile – the features that are most difficult for her to conceal even when duty so dictates. And then I spot her, no mistake possible: she is seated at a table at the center of the room. My hands slightly trembling I sit down, wondering if she is still willing to talk; if she is prepared to guide me through the complexities of human nature.

I want her to tell me all that she knows of doing fieldwork while being undercover – among people for whom their disguises are in a very real sense their continued lifelines. I want her to disclose her sources of scholarly legitimacy for studying rather than judging her informants; the transformation of her project from mere history and politics into ethnography. Most of all, I want her to tell me: what does humanity look like?

“What is it like to study the CIA?” I blurt out, wishing a mere nanosecond later that I could retrieve these words. For she fixes her gaze at me, performing bewilderment which could easily fool a less informed inquirer.

“The CIA? I don’t study the CIA – I study neoliberalism!”

We both muffle a snicker, after which she takes one long sip from her pint, and starts her tale. Soon the room disappears from view, and I find myself zooming through time, through distant landscapes, and finally landing on a rigid couch. Everything about the room is worn down, embodying the remnants of a once glorious future now far behind. The man sitting next to me – the one brought to life by her words – is old, crippled, a shell of someone once physically awesome. On the background the tv continues its infinite monologue; who could have predicted that a lengthy ballet production would be broadcast on that very evening.

The man’s voice is calm yet his stories are full of drama. They tell of events that few have dared to imagine being true, and even fewer have ever experienced in real life. One of them, I know, will haunt me until the end of my days.

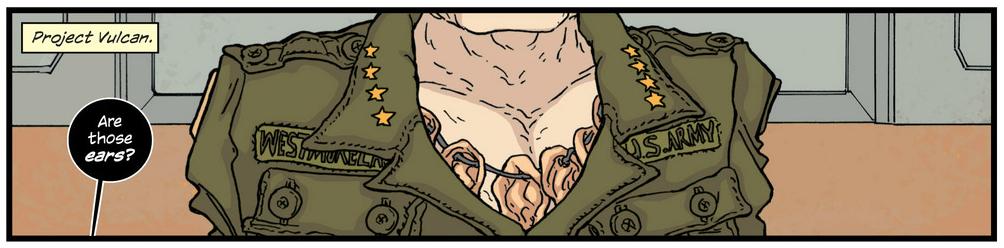

“I used to work a with a lot of guerilla organizations. With them you see things. People die. Sometimes you kill them. I had this collection when I was working in Laos. I turned it into a necklace, kept it wrapped around my neck. It was made of human ears.”

I feel nauseous, hoping I could disbelieve these words, the veracity of this disgusting memento. Fortunately the next second I am jerked back to the present day and the warmth of the pub as she interrupts her tale.

“You know, there was a rumor that this guy was the character of Kurtz in Apocalypse Now. The rumor wasn’t true, but the point is that it could have been.”

I try to restrain myself, but I simply fail, and exclaim: “How could you just sit there, listening to his words? How could you not hate him, to not want to publicize all of his evil deeds to the world? How could you just remain the ethnographer? What about what is right and wrong – about doing the right thing in the world?”

She remains calm, responding: “You’re not the first to ask! I have heard these same challenges numerous times by now. Once at one seminar somebody actually intervened in a large panel I participated in, only to make the point that this was not a legitimate target of anthropological inquiry – that I should have continued indeed to judge instead of aiming to describe, analyze and understand.

But it’s not that simple. You start your research seeing these monsters, but as you progress, you end up with people, real humans. The man telling these tales, I know, was in his youth an awful person at times– an alcoholic, a womanizer, basically an asshole. But when I met him, he was no longer that way, there was nothing fierce left in him except for his stories. His fame was still legendary, but in person he was just an old man, a sick one, and basically a good person to those close to him.

It’s really not that easy to understand or judge his actions nor those working in situations similar to him. We have to account for the time that has passed since they started their work – the world has changed, as has the organization for which they worked. When the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was set up, it was right after Hitler and WWII, after the biggest triumph of good over evil of modern times. Those were the first moments of decolonization and anti-imperialism – who would know that soon we would see a new period of an entirely different kind of empire coming into being, one led by the US?! The history of the Agency and how it became a contemporary manifestation of empire due to the Cold War, in particular, is very much a part of this story too.”

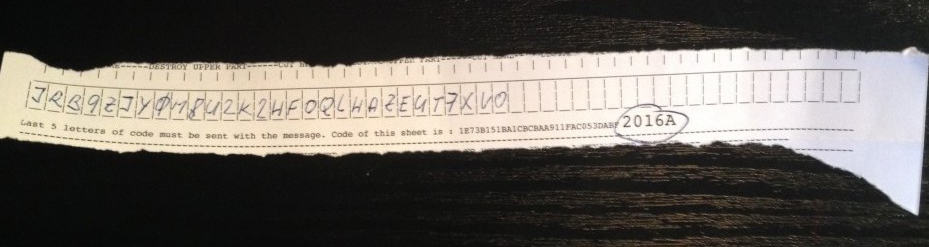

She continues: “Many who started working for the Agency were young and idealistic. For others it was just a good job opportunity that they sought to do as well as possible. How could they know what future decades would bring – and how would they know what working for the Agency would do to them? We have to remember the bizarre lives that their professional engagement expected of them: they had to live undercover also to those closest to them. And that cannot but mean certain deception.

I attended recently an event for retired agents at CIA headquarters, for which their families were invited. It was surreal to even be in this building – who could imagine that the CIA has an actual gift shop! Some adult children of retired agents were just learning of their father’s backgrounds – in essence kids grew up thinking that their dads ran flower shops or worked in an “office” or something; they really had these cover stories. Their families did not know!”

“Simultaneously to ask ethnographic questions of CIA officers is not the same as excusing them, for both as individuals and as a group they undoubtedly did become part of a larger problem. Studying them is not the same thing as ceasing to be critical. But the whole point of asking questions is to get at stories and not just at answers—this is what we do as anthropologists. Ultimately, it is these stories that fascinate us, and that make up our profession.”

She is clearly passionate about this point, only then realizing how long she has spoken without pausing. She sighs before continuing:

“This is not an easy project – far from it. But it is also fascinating, it offers unique insights into understanding the world. This applies to the Tibetan resistance movement, which initially set this project going. And in essence this project is identical to all others: I want to do it right, to do my informants justice by studying them as diligently as I would study any other group.”

She starts to shift, and I am jerked back to the present day. Our conversation has become much longer than I anticipated. I realize that my time is running out as she prepares for her exit. I feel privileged for this time, for I know how many others are waiting to talk to her; at how many places she is expected. But then I realize that something crucial remains without an answer. Hastily, I cry: “Wait! I need to ask you one more thing!” She stops, looking at me tentatively.

“What does humanity look like?!” I utter, desperately. She looks at me, both pensive and mysterious, finally uttering: “I could tell you, but I’d have to kill you.”

A wry smile, and she is gone. Without a trace. What else could I expect.

This text is a stylized version of the discussion that Allegra had with Carole McGranahan on her ongoing venture to study the CIA. She has previously written of her project here. This project is a continuation of her long- term research with the Tibetan resistance army Chushi Gangdrug, and will be a sequel of sorts to her book Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War.

I want her to tell me all that she knows of doing fieldwork while being undercover – among people for whom their disguises are in a very real sense their continued lifelines. I want her to disclose her sources of scholarly legitimacy for studying rather than judging her informants; the transformation of her project from mere history and politics into ethnography. Most of all, I want her to tell me: what does humanity look like?

I want her to tell me all that she knows of doing fieldwork while being undercover – among people for whom their disguises are in a very real sense their continued lifelines. I want her to disclose her sources of scholarly legitimacy for studying rather than judging her informants; the transformation of her project from mere history and politics into ethnography. Most of all, I want her to tell me: what does humanity look like?

This is horrible. Spying on people isn’t ethnography, it is spying on people. Is this what anthropology had become, advertisements for the CIA?

Did you read the article at all? The person interviewed is studying the CIA. This has nothing to do with the CIA studying people. It seems like you literally just read the article title.

Many methodology questions about this research. Who is funding it? Did it receive IRB approval at her university? Have the interviews been approved with CIA (as required by the contracts of these CIA employees)? What guarantees were made to claimed CIA employees? How are claims verified? etc. Perhaps Prof. McGranahan could reply here?

Warm thanks for this comment – we will contact Carole McGranahan to discuss this!

Hello all–this is ethnographic and historic research I’ve been doing since the late 1990s with retired CIA officers, combining fieldwork and “ethnography in the archives.” Some of it is already published in my book Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War (https://www.dukeupress.edu/Arrested-Histories/index-viewby=author&lastname=McGranahan&firstname=Carole&middlename=&sort=newest&aID=712801.html), and I am currently continuing this research in relation to US empire. I am not working with currently active CIA officers so can’t answer questions about what permissions, etc. that might entail. Finally, an ethnography of spying is very different from ethnography as spying. My project is the former, but given the history of the discipline of anthropology, of times when anthropologists have been falsely thought to be spies, and times when anthropologists have been spies (or vice versa), this distinction is important.