To set this week in motion we revisit a theme that we seem unable to escape: boredom. Whether at academic conferences or the elaborate corridors of international diplomacy, this sentiment greets us in continually novel cloaks. Two years ago we organised ourselves for an EASA 2014 panel on the topic – yet we still seem that there is more to consider. Why has boredom become such an epidemic in our age, and why do we collectively accept to settle for it? The below post, published originally in August 2014, shares some of our thoughts on the theme.

*******************

‘Moments when things happen’ AKA ‘windows with meaning’

On August 2nd, 2014, we ran a panel titled ‘Boredom, Intimacy and Governance in ‘Normalized’ Times of Crisis’ at the EASA 2014 in Tallinn. Now, when organizing a panel that is inspired by sensations of boredom caused by similar panels organized previously in a similar fashion – introduction, 6-7 papers, discussion – one sort of sends out an invitation for failure. Or at least, for stark criticism. How to escape reproducing exactly the same sentiment – boredom – that the panel in question wishes to tackle analytically?

This was the evident challenge that we had to mentally overcome as we prepared for the event. Simultaneously there was also something more: a sentiment that despite of our best efforts, we struggled to get anywhere with the theme. Sure, we had tried, first via posting some preliminary thoughts on the topic almost a year ago, and then brainstorming further when we formulated the panel abstract.

We had studied the writings of those who had labored with the theme before us – we went through Lars Svendsen, Lauren Berlant and many more. All inspiring and brilliant, and yet we failed to make noticeable progress. We continued our search while time grew thin in between our unfinished thoughts and the eventual paper deadline, finally arriving at something highly unsatisfactory while sharing our delivery pains publicly too.

It is with this baggage that we arrived in Tallinn, where we enjoyed the opportunity to meet up with our collaborators – the wonderful Sylvain Piron, Antonio De Lauri, Daniele Cantini, Bruce O’Neill, Amanulla Mojadidi, and Ghassan Hage as our discussant (Heath Cabot had to regrettably cancel). We schemed a bit, talked of the protocol for maintaining familiarity and order, as well as of how we would dive into the experimental.

“A window is meaningless unless you’re in an enclosure”

One concrete motivation for the panel was offered by the following question, summarized by Julie Billaud and shared during the panel via our (frenzied) Twitter account:

Indeed, as we criticized already almost a year ago in our ‘Savage AAA thoughts’, it feels increasingly that our collective creativity is being conditioned – tamed – by the imposition of predetermined formats, be they in terms of time, style or word count. What original is there left for us to say – and why do we all succumb to this reality of, what to us, increasingly feels as merely ‘going through the motions’ with continually decreasing room for creative engagement?

In his paper, Sylvain Piron (at the moment of writing this post the man of the hour for his direct criticism of Elizabeth Povinelli’s keynote) helped us contextualize our modern condition via a detour to early monasticism – familiar both with the demon of boredom as well as the sin thereof. “Akedia (boredom) is the sin of not fulfilling what you’re supposed to be doing in the world.”

Can it be as simple as this? Are we bored when we feel that distinct predefined formats – be they those imposed by bureaucratic processes or standardized slots for conference presentations – prevent us from fulfilling the purposes that we see ourselves as holding as a part of this world? What about the time that separates us from the past to the present: are the emotions discussed by Piron in medieval times still the same today; are bridges across time truly as effortless as this to cross?

Perhaps so, for Sylvain Piron also reminds us of the predecessor that monastic institutions set to modern bureaucracies, prisons included. In addition to introducing familiar institutional designs, there is also a crucial ‘mindset’ that monasteries left us with:

Institutional boredom; bureaucratic boredom, the need to be incessantly ‘doing something’; to stay in motion, as Tim Ingold has phrased the meaning of being alive. There is certainly something here.

We are led back to the words of world-renowned American writer David Foster Wallace – a torn figure who committed suicide in 2008 – and what he said of the modern man’s condition. To be able to live, existentially as well as physically in the case of Foster Wallace, one should develop an ability to endure boredom, to live through, with it and perhaps even, to embrace it. Without such a capacity, he argues, human existence is doomed to permanent suffering.

Is this really the case? If bureaucracy, audit cultures and their corresponding formats such as assessment exercises and appraisals, as well as aesthetics such as reports, conferences, power points presentations, have become ubiquitous features of our modern times, is it necessary to embrace boredom to lead a happy life? Is there absolutely no way out except suicide, social or real?

Boredom as flirting with suicide and death; social death or the real kind. The theme certainly comes up in the discussion that ignites as our panel continues.

Is there another way out? If we ask Foster Wallace, the answer is ‘no’.

“I learned that the world of men as it exists today is a bureaucracy. This is an obvious truth, of course, though it is also one the ignorance of which causes great suffering. But moreover, I discovered, in the only way that a man ever really learns anything important, the real skill that is required to succeed in a bureaucracy. I mean really succeed: do good, make a difference, serve. I discovered the key. This key is not efficiency, or probity, or insight, or wisdom. It is not political cunning, interpersonal skills, raw IQ, loyalty, vision, or any of the qualities that the bureaucratic world calls virtues, and tests for. The key is a certain capacity that underlies all these qualities, rather the way that an ability to breathe and pump blood underlies all thought and action.

The underlying bureaucratic key is the ability to deal with boredom. To function effectively in an environment that precludes everything vital and human. To breathe, so to speak, without air. The key is the ability, whether innate or conditioned, to find the other side of the rote, the picayune, the meaningless, the repetitive, the pointlessly complex. To be, in a word, unborable. It is the key to modern life. If you are immune to boredom, there is literally nothing you cannot accomplish.”

― David Foster Wallace, The Pale King (italics added)

But maybe it’s not all as dark as this. In his paper Antonio de Lauri discusses the inevitable companionship of humanitarian work and boredom: since actual work in ‘the field’ is a rarity when compared to bureaucratic paper work, “All humanitarian workers have to go through boredom”. Simultaneously boredom becomes a shared experience strengthening collective identities, creating positive bonds, solidarity. This is also what Heath Cabot’s paper (in abstentio) showed, yet in a highly differing context, namely the asylum crises of Greece.

Boredom has also another crucial analytical component: it reminds us of a distinct ‘samenness’ in cases where there is an almost intuitive pull toward seeing radical difference. As Daniele Cantini discussed in his paper,

“Political islam not very influential in the lives of Amman youth – how to kill time a much more pressing concern!…After graduation, Amman youth have nothing to look forward to due to social constraints and expectations. Stuckedness settles in.”

In Cantini’s paper the Islamic youth – in the heap of the Arab Spring – are not all revolutionaries engaged in schemes for radical social change, as popular imaginations prevailing in recent mainstream media, for example, would have it. Rather they are idle youth who are bored. And further, boredom becomes the most acceptable route to take; as

Boredom as existential stuckedness, as the opposite of ‘being in motion’. All of our analytical avenues bring us back to this notion. Yet what you do with boredom – how to solve the dilemma of ‘stuckedness’ – varies dramatically, of course. Bruce O’Neill shares his analysis of unemployed and uneducated Romanian men who end up becoming prostitutes – in part because of boredom.

“It’s not good money. Every other work requires a high-school diploma. In the end of the day you just feel so bored.”

Boredom as the embodiment of social exclusion, as the opposite of belonging. But, as O’Neill asks: What does belonging in a consumer-driven society look like? We ask: What is left for us if both inclusion and exclusion end up having the same face – that of boredom? Are we bored because we have to choose the smallest common denominator in order to communicate and share a reality, particularly on the global scale? “The world becomes boring once it is transparent” Antonio de Lauri summarizes. Is this truly the case?

Boredom as a form of abandonment, despair, absurdity, as the absence of justification for being, as a form of social death? Boredom as “the thousand nothing” depriving us of the forthcoming?

As Ghassan Hage rightly points out, citizenship is usually associated with notions of hope. When one becomes a citizen, one becomes hopeful. What does it mean when citizenship is a closure instead of an opening up on the world? When citizenship means the impossibility to live multiplicity? The politics of boredom is certainly a radical politics which encompasses element of refusal of the mono ontological.

Our heads still spinning and discussion in full swing suddenly something happens, a bell rings. It is the demon of noon who has been summoned to conclude our panel. Parts of this we knew, parts of what has transpired has been unkown; the choreographed and predetermined shake hands with the spontaneous, the experimental.

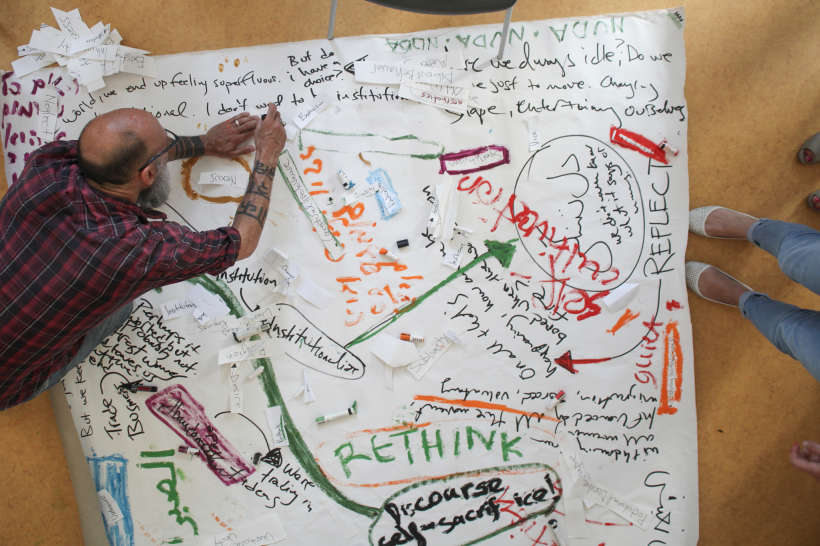

Amanullah Mojadidi takes the floor, rolling out a large blank sheet and markers. He distributes pieces of paper, all accompanied by words from the grandiose to the mundane. We all take our share, seizing further his invitation to create a background of sound by reading them out. Chanting, muttering, matter-of-fact utters – the room is filled with sounds as people leave their seats. Some join in on the artwork, a spontaneous market for keywords forms, a few people leave the room.

Soon it all ends, with no one quite sure of what transpired. What was accomplished – or is this the wrong question to ask? Was ‘boredom solved’ – or was it never a problem for us to solve in the first place?

A few days later we watch the video compiled of the presentation collectively with friends and colleagues as we launch Allegra Lab’s physical headquarters. The video brings back the sentiment that we left our panel with: as a moment when ‘things happened’; as a window through which to gaze in and out and see things with meaning. The analysis continues, remains open-ended, but there is some newfound certainty: as Ghassan Hage summarized it in his remarks, boredom is fundamentally a relationship. This is how we have to proceed in its analysis.

A year ago we declared Allegra to be a social media experiment to find creative ways to fill the ‘DEAD SPACE’ that exists in between ongoing societal and scholarly debates and eventual traditional scholarly publications appearing in a few years. Today we celebrate everything that exists in this dead space, illustrated by this post – the original post that set our thought-process in motion; the follow-ups that developed them further; the tweets that form a live archive of the panel’s highlights and also intercept this post; the video that we can jointly share the mood of our event, and this post that allows us to share our thought process further. To us, all of these are moments when ‘things happen’ – and moments that we had no means to share prior to Allegra’s creation.

We know that we may (still) represent a minority but we are convinced: jointly all these steps are at least as interesting if not more so than the eventual traditional publication that we will one day produce. Whether we are right or not, it is all these steps that we celebrate as Allegra turns 1.

Happy Birthday, ALLEGRA – and many happy returns of the day!

Happy birthday Allegra ! You have certainly accomplished a filling of dead space with scholarly reflections, creativity, humour and inspiring thoughts 🙂

Happy birthday, friends! You’ve already done so much. Here’s to the future!