Let’s start our ethnography slam with contributions by David Bukusi, Silke Hoppe, Justine Laurent, and Natashe Lemos Dekker. If you want to know what an ethnography slam is, here’s the introduction.

Doctor’s Slam

by David Bukusi – Daktari

No one’s gonna talk to me

Coz I’m The Daktari,

Get an appointment

Yeah, get in line!

Yet here I am in Amsterdam

Where the Sun don’t shine,

Men are in Trouble

Men are on the line!

There is a Prozac bubble

Some call it mental Health

But when you want to kill yourself

It may be lack of wealth

20 years of HIV

And nothing new coming through

I’m kinda tired of WHO

Telling me what to do

I’ll be replacing objectivity with reflexivity

I’m sorting out my psychiatry with anthropology

I don’t want to continue talking about myself

No no no, let’s focus on mental health

I want to get into the field

To make sure I get the yield

I want this info

To help figure out why

Men do as they do

And why sometimes they die

How do I do this?

Through Ethnography

With all its ways, means and methods

It’s great for stories, tales and records

How will I report it,

I ask myself softly?

I do have some clues,

I’ll work them out nightly

But others here are telling me

To take some liquor

Coz this will help the lines

Flow faster and quicker

Now I really need this info

Do you get my drift,

Coz I’m the Daktari

And I’m on my shift!!!

Personally, I hate talking

by Silke Hoppe

As one of the organisers of the ethnographic writing workshop, various people approached me in an attempt to replace the ethnography slam with some discussion on writing. “It’s a writing course so why can’t we do something more on writing? And also, listening for three hours to other people’s presentations will just be really boring”. Since I myself felt a bit ambiguous about the idea, I voiced my colleagues’ concerns, but in the end we did not change the programme.

After a lot of stress and frustration resulting partially from the fact that the ethnography slam should be done in groups, everybody managed to prepare something.

While on Friday morning most people were still a bit sceptical, many tired from the intensive week, this completely changed after the first person did the ethnography slam.

All of a sudden we were no longer intellectuals competing for excellence, we were human beings touched by the vulnerability of our colleagues.

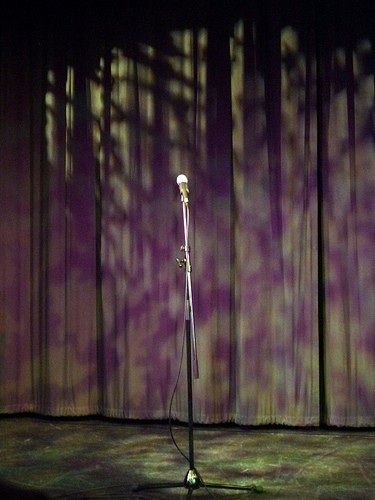

In retrospect, I think this vulnerability provoked so much resistance in the first place. Although not everybody feels confident as a writer, writing about scientific concepts and theory in a somewhat distant manner feels safe. It is what we do as academics. We also sometimes translate those writings into presentations, adding a picture or two to our Power Point slides to make them more interesting. But trying to engage with our audience and adding something personal sounds scary. It involves stepping out of our comfort zone and trying something new which might backfire and make us look (and feel) ridiculous.

To me, the fact that each of the workshop participants dared to be vulnerable made the ethnography slam so special. Doing it, we did not only learn new things about our colleagues’ research projects or personalities, the ethnography slam transformed the whole group. Each time I meet one or another workshop participant in the department hall, I smile as I remember something funny, personal or provocative from that person’s slam.

Below is my slam, in which I encourage people to embrace their vulnerability. Upon rereading it, however, I wonder if I give a good example and am myself embracing vulnerability, or if am I just being angry?

Personally, I hate talking. Well, not all kinds of talking, but talking about difficult things, and by difficult things I mean painful things. And by that I don’t mean talking about whether I should sell my beloved car in order to go on a holiday, but I mean things that unsettle me at the core of my heart.

But don’t get me wrong. It’s not so much the content I find painful. It’s people’s reaction. If, for example, I tell people about my muscle disease I get replies like “There are many people who do not have so much strength in their arms and legs,” or “Actually I am also feeling very tired.” Okay, but you are still able to get on that fucking stage and I am not.

I often feel there is no space for pain. “Think positive and don’t despair.”

And yet we live in a world in which we are encouraged to talk about our problems and pains. “Speaking is healing,” they say, “Silence is suspicious.” Well, it certainly didn’t heal me to get stupid comments when I talk about my pain. Actually it just made matters worse.

As anthropologists we encourage people to talk about painful things. In our education we are taught that it is important to ask the right questions. “Only use open questions. No ‘yes or no’ questions. And by all means avoid those leading questions. You don’t want to be humiliated later by your supervisor for using them.”

But we don’t get any teaching on how to be a good listener. Or how to respond to intense pain, sadness, desperation.

Based on my own experience, I hate it when people try to relate my experience to theirs and believe that it is similar. “I know exactly how that feels.” No, you don’t.

This all might sound a bit harsh. But I don’t expect perfection. I don’t wait for that perfect sentence giving me the feeling of being completely understood. Although if I had to say what a perfect reaction was, I would say that my colleague’s remark “That sucks!” came quite close.

Instead of receiving a perfect response, I would prefer some vulnerability. Why do we find it so hard to just pause and admit that we don’t know what to say?

Photo by emmajc (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Out Loud

by Justine Laurent

I have been doing fieldwork with a lot of scientists and people from the probiotics industry in the Netherlands. Here is a compendium of some recurring sentences I heard – which, I want to believe, stemmed more from me presenting as a young female researcher rather than from my failure as a researcher.

***

Are you a journalist?

Are you a student?

Aaah it’s our philosopher!

Are you a social worker? Or some kind of nurse?

Do you want to do science communication?

You think you can tell people that we are doing something really good?

Do you understand what I am telling you? Is it too simple? Too hard?

Can you tell me again what is your research about?

Do you really want to know about the detail of how I run this algorithm to work on this bacteria?

Well, this is the freezer you wanted to see. Not much to see, right?

You know, this is not really interesting.

But are you not talking about what people think of good bacteria?

What do customers want?

Well, now you kind of know our whole strategy!

You won’t tell that to our competitors, will you? Oh, and by the way, can you tell us how they do this or that?

[after talking for an hour, and having agreed to being recorded] Of course, all this is off-record!

Well, I would reframe it a bit, I mean, for you it’s all the same, but this is for the image of the company …

What you wrote is very nice, but this is not very useful for us, can you tell us the perspective of ‘the people’ [i.e. customers] instead? Well, I know you said you did not work on that, but this would be more useful for us. You should make an effort. After all the hours we gave to you…

***

Writing this short piece with the specific aim of reading it out loud wasn’t seamless.

First came the reluctance – “We are already doing presentations at conferences, why would we have to do this?! Oh, and really, on a stage?” This was a shared feeling, it seemed, among us PhDs in anthropology having signed for this writing workshop. Writing, not performing.

Second, curiosity – Tanja managed to dispel some of this mix of annoyance and apprehension when she screened a few examples of impressive poetry slams. “Oh, so this is what is expected of us, completely unrealistic, but seems so much more fun than suffering while reading your paper at a big conference through a half asleep academic audience, this can be fun” I thought, while self-doubting about not being a native speaker of English started eating me alive.

Third, the process of writing the text came to be completely transformed by the fact that it was going to be read out loud – and that it should at least partially, be ‘creative.’ It suddenly became clear: “What better words to say out loud than the ones I had been spoken to me?” It was a great occasion for me to make use of these (at times) painful sentences I had heard during my fieldwork by transforming them in a creative exercise mixed with a little bit of self-derision!

Fourth, reading. It was not like these difficult (for me) academic exercises of reading your paper. It became, as soon as I managed to articulate the first sentence with feelings ranging from fear to amusement, a pleasant exercise. I was talking to my colleagues in front of me. And I was gaining their attention and engagement by making them laugh with me.

This entire morning of performances filled me with astonishment. These academics, some of whom I had seen shaking, blushing, stumbling, hesitating while presenting their papers where occupying the space with their honest and poetic performances. We read, a lot of us still shaking and blushing, but with a different voice, another presence. Filling the immense room with our accents, our stammering, our sweat, our shouts, our poses, our spit, our hesitations, our tones, our smiles, our tears, our mistakes. The situation spoke volumes.

We needed to bring our bodies (back) into our texts.

How to import the process of performing that we have learned during this ethnography slam to academic presentations? Not that we should all perform our texts at all times, although more of that would be welcome in a feminist academic environment trying to open up the homogeneity of the norms (that’s what I realised when witnessing some innovative performances and presentations at a conference a couple of months later). However, maybe embodying our texts in order to relate to a situated audience – instead of showcasing our research (for PhD students especially) and deliver a specific smart message – could make for a better reading and writing process.

Photo by Nicolas Nova (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Standing at the bedside

by Natashe Lemos Dekker

Her nightgown is lifted up to her left thigh while she is lying in the wooden bed surrounded by the same colour nightstand and wardrobe. There’s nothing remarkable about them, but plain light brown wooden furniture, the same like in any of the other rooms.

Her daughter, son and granddaughter are sitting around the bed. She moves her hand across the mattress, first slowly, then faster as if she were looking for something, trying to grab it, failing at it and grasping the air between her fingers. Then her hand opens again. This time she manages to grab her nightgown, pulls at it, as if she were trying to cover herself. Her eyes are not just shut but closed with a deep frown that spans her entire forehead. Outside the sun is brightly shining, and in the distance I even hear some birds; such a great contradiction to the scene that is unfolding before my eyes inside this small room. The air inside is heavy. At first, her mouth opens, and she gasps for breath. Each time we fix our view on what’s happening, in search for a sign. Will this be her last one? No, her mouth closes and opens again. Her daughter takes a deep breath and looks at her brother, eyes filled with tears. At that moment, the woman lying in bed starts screaming, bruised sounds, unfinished. The rooms gets filled with it, time and again. Each time I squeeze my hands. We all look at each other and stand there. Stillness comes to the body, and fragmented movements are transgressed by traveling into lightness.

***

Participating in the ethnographic writing workshop was an amazing experience and opportunity. It made me think critically about the use of different voices in text and which suits best for the theory, epistemologies and eventually stories I want to bring forward. The workshop also created time to reflect, write and learn in an informal and affirmative setting, with the support of fellow PhD students and senior researchers.

Having to write ethnographically asks for slowing down, reflecting, thinking back about the experiences and moments we have witnessed as researchers, and translate these into words on paper. Words that make sense and sketch out a portrait. Writing and then reading this vignette out loud during the ethnographic slam, brought me back to the bedside, to the broken smiles of family members around it, to their confusion and despair.

As I trembled and felt vulnerable reading this to the public, I came to the core of my research.

*****

Featured image by Bea Mahan (flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)