Yesterday we opened the AVMoFA’s first summer exhibition – Die SommerWende – and today we are very pleased to meet the artist, Axel Schön, in person and speak with him about these works – and about the art of photography and science of documenting human experiences.

Allegra: Hello Axel! It is a pleasure and honor for us to be curating this virtual personal exhibition. It would be interesting for our Allies to know a little bit more about you and your work. What first brought you to the ex-Soviet Union and inspired your interest in travelling there? What is your most vivid impression of this encounter?

Axel: My first encounter with the “post-soviet” was not inside the Soviet Union, but in my hometown Kiel, where I met people from Russia. They were performers and musicians touring Germany and participating in different cultural events. It was in 1989 and it was shortly after the historical “Wende” – the opening of the borders between Germany and Germany – and at the same time the opening of Russia to the West. I got in contact with these artists from Russia and they invited me to visit them in Leningrad – yes, back then it was still named Leningrad! This is how I first travelled to the former Soviet Union. And what was it that impressed me the most? It was probably the open-mindedness of these artists, young men and women, very vivid, curious, and positive – I was really truly impressed!

Allegra: If you had only three words to describe your first trip to the former Soviet Union, which ones would your choose?

Axel: Three words? I would choose disorder, dirt, deficit.

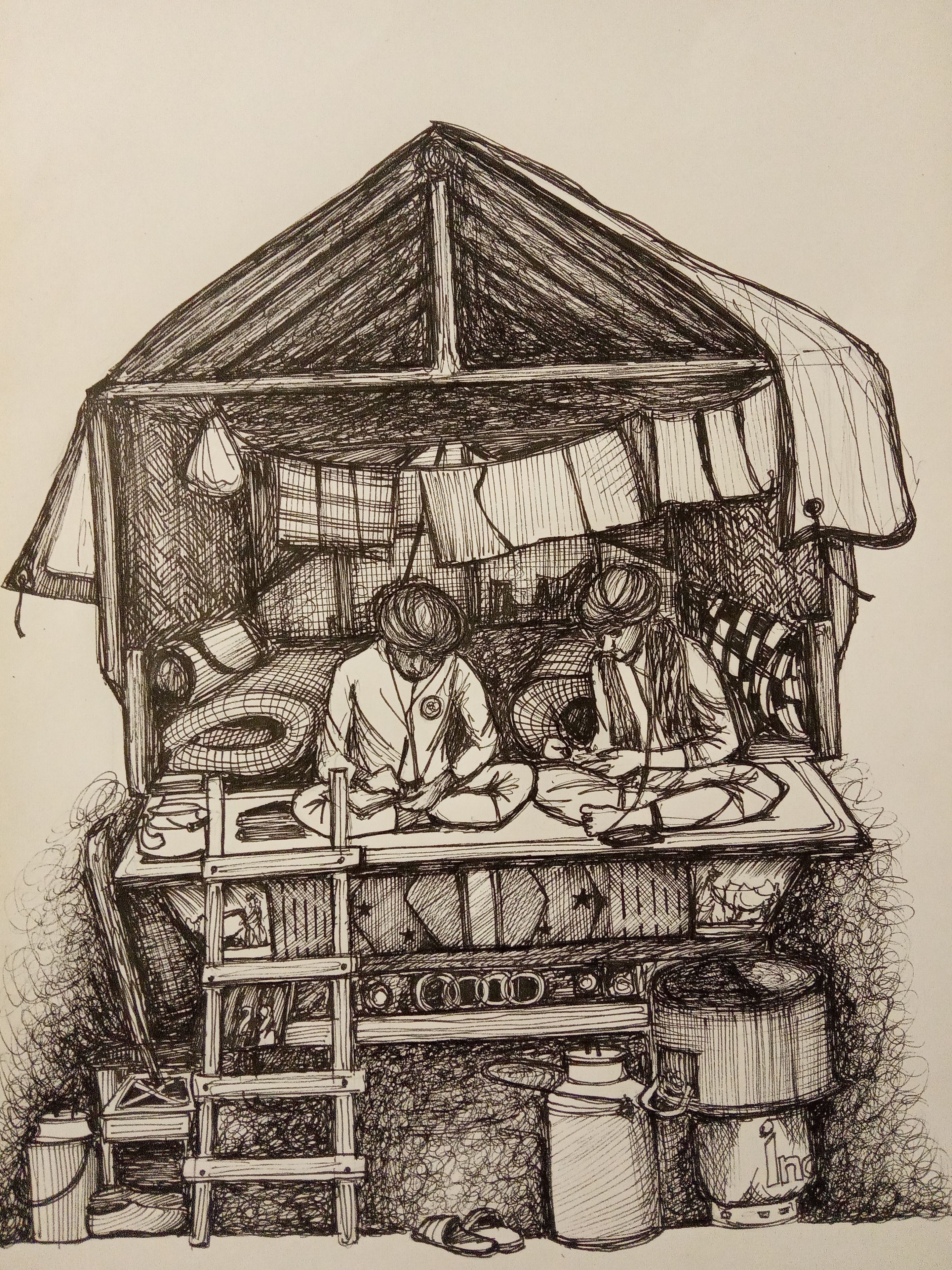

Allegra: Summer for anthropologists usually means fieldwork – going on trips to collect research data. What are the main principles you hold on to when you work ‘in the field’, in particular, when you capture people and their daily lives with your camera?

Axel: Well, I do not do research. I take pictures and I call my type of work street photography no matter where and when it takes place. One of my main principles is to get in contact with people respectfully. This means both to be a friend and be friendly. I try to be close, not shooting from a distance with a tele-lens, but come very, very close with a wide-angle lens.

I want to be IN, to be inside of what´s happening, to be a part of it – not a stranger who is “robbing” reality and “steeling” parts as pictures.

Another important principle is to be offensive/outgoing, not defensive – not being afraid of what I want to photograph. By the way, I actually took photos of people from the countryside working in the fields, that’s what I would call fieldwork.

Allegra: The name of this exhibition is Die SommerWende – the Summer Change. Do you think it is possible to capture change in photography? What does change mean for you in artistic terms?

Axel: I don´t think it´s possible to capture change in photography. One can only capture this very moment, the situation that is unfolding NOW. Afterwards, it may be possible to say that those pictures captured some change, or has become iconic for some transformation. Maybe. In my artistic work change can randomly have meaning as it does in these pictures taken in the 1990-s in post-soviet Russia. But besides this I do not usually work in this context. I just show what and how I see, different to others, I hope…

Allegra: How did your work in Eastern Europe influence your artistic style? How did it affect your later works?

Axel: Well, first of all, my work in Eastern Europe gave me more courage to do my work in general. There were so many situations when I had to cross borders, mostly psychological borders, so I learnt not to be afraid of the subject I wanted to capture. If I really want it, I shall do it! On the other hand, this experience did not change my photographic style and aesthetics much.

Gorbachev | Vaganovskoe cemetery, Moscow (Russia), August 1992. Mikhail Gorbachev with his wife Raisa at the grave of August putsch victims.

Allegra: One of the pictures we have on display is with Mikhail Gorbachev and his wife Raisa. Could you tell a little more about this encounter?

Axel: The story about the pics of Mr. Gorbachev and his wife… let’s see. It was in August 1992, the first anniversary of the August coup against Gorbachev. I was driving back from the Urals and Kasachstan approaching Moscow. On my long journeys traveling the former Soviet Union, before that memorable day, I did not stop a single time to pick up a hitchhiker. Funny enough, that person I picked up on the highway turned out to be a volunteer from Reuters, the renowned press agency, and a foreigner too. We talked and I decided to stop over in Moscow and visit the agency. That turned out to be a good idea. I found out there that Gorbachev was visiting a cemetery the next day in the center of Moscow. This was to honor the memory of the victims of the coup buried there. I went there and waited with all the press for the Gorbachev couple to appear. But it was only after the official part of the event that I had a chance to get close enough to take a shot. That’s the story of this picture…

Allegra: We all know that the time of democratic transition – the late 80-s and beginning of 90-s – were a very hard time for most people in Eastern Europe. Back then the divide between the ‘rich and progressive’ West and ‘poor’ East was very drastic. In addressing the relationship between an artist and the depicted people, how was it for you to experience this difference? How did your relationship with locals evolve on your trips? How did people react?

Axel: Thanks for this question. The encounters were very different. For the most part, your “idea” of a collision between me, the guy from the “rich and progressive West” and the “poor East” fits well with the experiences I had while working on a series of portraits of people from villages near by Novgorod in Northwest Russia. This was a really different world for me as I met quite a few very poor people. Many suffered from alcohol abuse and carried with them a sense that something was lacking and didn’t see a perspective in their lives. In this case, I prepared for my reportage by searching for a personal entry. A year before, I visited Novgorod with a convoy of humanitarian help and made friends with some people there, in the city, who thereafter helped me to establish contact with the people in the village. Eventually I lived with those people so that the locals could get accustom, in a natural way, to me as a photographer.

Over two months I lodged in the house of an old woman in the village. People got used to seeing me with my camera. I was always with my camera because I never left the house without it.

There was more of a ‘classical reportage’ in other situations. There are a few pictures in the SommerWende that depict traditional Neptune festivities; I took them at the shores of the Black Sea in Southern Russia. In this case, I was acting like a gambler, throwing myself into the action, taking pictures without searching for a direct contact with the people. I took the pictures with a 20mm-lens, which means that I was literally IN the picture. There I was a stranger who successfully penetrated a group of party-people and dissolved within it. It was possible because they were extremely focused on their celebration and, among other things, slightly boozed (smiles).

Allegra: What does it mean for you to capture ‘the right moment’ in street photography?

Axel: For me, it´s very much about patience and enthusiasm. Definitely, it is hard work – you have to really concentrate on what´s going on, be aware of any sudden action and attraction, be ready to capture it. From a more technical perspective, back then in the 1990-s it was much harder because you had at a maximum the choice of 1000 ASA films – compared to today’s possibilities it feels like a joke. Modern digital cameras can be pushed up to ISO 12800 and higher. With that sensibility you can generate shutter-speeds to make sure you won´t have blurred pictures. Yet, leaving the technicalities aside, for me the most important working principle is to be close, to be IN the action; and it´s good to find a personal contact too.

Allegra: I know that you are fluent in Russian. What is your favorite word or phrase? Which Russian word or phrase describes Russia in the early 90-s and why?

Axel: Maybe it would be “тусовка” (“hangout”). It seems to me that during that time, that difficult time, people were hanging out a lot, especially in the cities. I had a feeling that all my friends were constantly ‘hanging out’ and having fun at parties. I guess it helped them to maintain their optimism in order to somehow get through it. I think in English there is an expression “dancing on a volcano.” There were so many problems around in every sphere of life, but it was a time of starting from scratch so nobody had anything to lose – just to win!

Allegra: Finally, as you know, we will continue next week with a book review on food culture in post-socialist countries. What was the most exotic or strange food you had during these trips to Russia and Eastern Europe?

Axel: The most impressive food experience happened during one of my road trips. I was driving with my girlfriend down from Ekaterinburg to lake Aral in Kazakhstan. The road was very empty. Just a few other cars and trucks drove by in several hours through the desert. At some point we stopped at a kind of a service station by the road. It was a very simple open cottage with some trucks parked in front of it. We wanted to ask for some food, and you know what happened? The people from the cottage went to slaughter a sheep, right next to the cottage, to prepare a kind of goulash for us. This was the most direct food experience I ever had – the meat in our dish came from that living animal, not from a supermarket shelf. Another food I really liked was “простокваша” – I think it´s called clabber (sour milk) in English. It was usually served cold from the fridge and with sugar. It was a very refreshing beverage for the hot summer days!

Allegra: Thanks again Axel for this insightful talk. Hope to see you with Allegra again soon!