I arrived in Geneva for the first time in July 2010, hoping to spend a few days getting my bearings before starting research at the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD). Eager to begin exploring but without my UN observer badge yet in hand, I decided to set aside my misgivings about doing something very “touristy” indeed: I handed over ten Swiss francs and became “one of the 100,000 visitors who take the tour of the Palais des Nations each year.”

The Palais des Nations was once the headquarters of the League of Nations, and is now the center of UN activities in Geneva. It contains several large conference rooms for meetings of diplomats and international experts, many outfitted with booths for simultaneous interpreters and balconies to accommodate NGO observers. In the entryway to one such room’s main floor – the diplomats’ floor – I found this sign announcing “Smoking Discouraged.” I use the term “announcing” advisedly here; what these two words are emphatically not doing is “demanding” or “mandating.”

Oddly enough, this would not be my last lesson on the soft regulation of smoking at UN facilities. The following summer, I traveled to New York to do archival research in the UN’s Dag Hammarskjöld Library. As this was my first visit to UN Headquarters, a member of the library staff who I will call Lara volunteered to meet me at the security entrance to make sure that I didn’t get lost. As we walked on sidewalks and past buildings both covered in scaffolding, Lara apologized that I had to visit at a time when construction was hampering so much of UN Headquarters’ beauty. She explained that the main buildings were undergoing remodeling and retrofitting, and remarked that there was no doubting that they needed it. “If you can believe it, there are still ashtrays built into the men’s rooms!” she said with a laugh.

Lara went on to note that the ashtrays were clearly signs of a bygone era, as now there are rules against smoking in UN buildings. The rules to which she referred, it turns out, are well known at the UN because they were hard won – and only partial – victories. They began with former-Secretary-General Kofi Annan, whose attempt to enact a smoking ban in 2003 met formidable opposition.

Some member states’ diplomats argued that Annan lacked the legal authority to declare such a ban on UN-administered territory. Among them was Russian ambassador (now Foreign Minister) and reputed chain-smoker Sergey Lavrov, whose protests included some characteristically quotable arguments. Lavrov dismissively referred to the UN Secretary-General as merely “a hired manager” for UN buildings, the ownership of which was vested in UN member states. Annan’s sole jurisdiction, according to Lavrov, was over “his underlings” – i.e. UN staff – and not members of diplomatic missions.

According to subsequent reports, many smokers ignore the ban and its enforcement is spotty at best. Such reports in turn occasion predictable commentaries about what this experience reflects about the UN as a whole – a scene of tiresome, dithering debates where, even in the rare case that parties reach an agreement, they are unable or unwilling to enforce it or even abide it themselves.

The typical ineffectiveness of the UN system, diplomacy, bureaucracy, soft power, or whatever else, on full display.

Such criticisms have their place, but I find more illuminating insights in the further reflections Lara offered on the smoking ban. Having noted the ban’s existence, she admitted that violations are often allowed to slide.

There are people from all over the world here, Lara continued, and naturally they bring different norms, codes, cultures, and practices. “Who would want to go up to people and tell them to their faces that they aren’t allowed to smoke?” she asked. Furthermore, at the UN, you never know who it is you are talking to. You wouldn’t want to offend an important government representative over a cigarette.

Lara concluded this monologue by predicting that the problem would resolve itself without the need for such uncomfortable interpersonal encounters. The aforementioned cultural differences, she believed, would be surmounted more organically. After all, attitudes around the world were already changing, and diplomats’ increased exposure to norm-compliant behavior would continue to expand awareness about the issue. Noteworthy for its absence was any suggestion that the matter was as simple as the UN or its member states lacking the authority or will to enforce the ban.

I’ve thought about this commentary a good deal, not because I care very much about the regulation of smoking, but because of its resonances with my actual research area – the regulation of human rights treaty obligations. Listening to Lara’s analysis of the former, I couldn’t help but hear her talking about the latter. I say this not only because her description of reticence to speak in a voice of strict enforcement reminded me of treaty bodies’ cautiousness in confronting state representatives about contraventions of human rights treaty obligations. Her rationale for this reticence – its goal of reinforcing good will and sociality as enabling conditions for future influence, and ultimately, real change of behavior – is also entirely consistent with my ethnographic findings on CERD practice (Clark n.d.), and I suspect that of other treaty bodies.

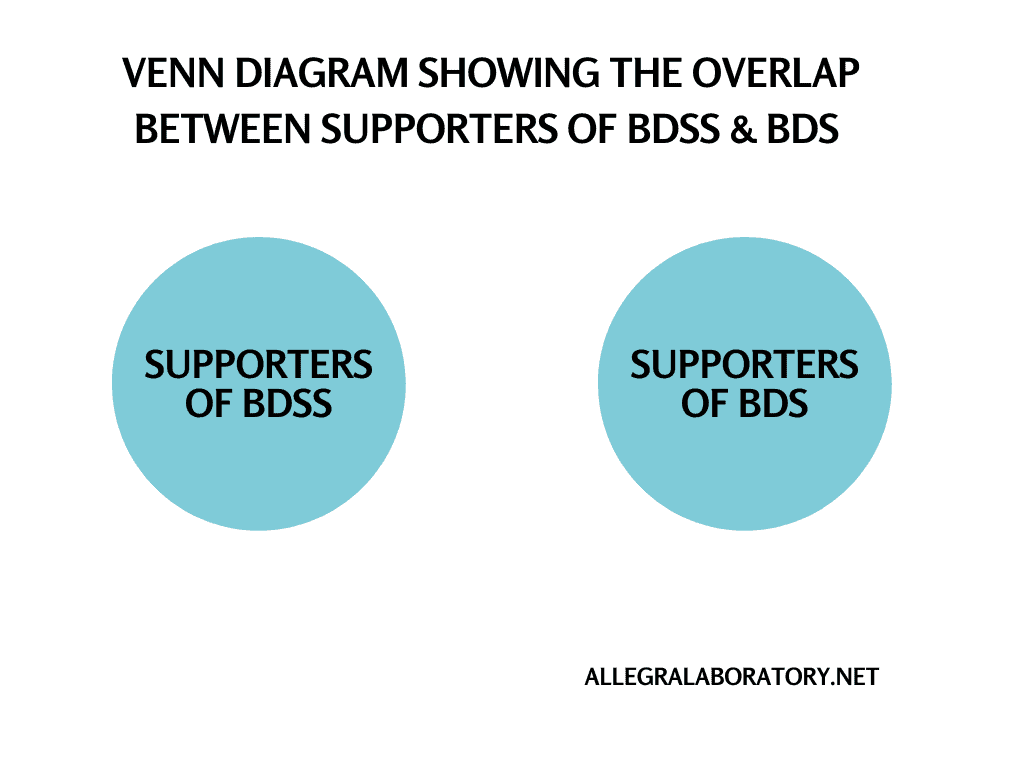

Importantly, in neither case is it enough to explain inconsistent enforcement as simply powerlessness or ineffectiveness. In fact, international legal scholars Ryan Goodman and Derek Jinks (2013) argue that, often more than material inducement or even overt persuasion, it is “acculturation” that leads states to realize their legally binding commitments to international human rights norms.

Understood as a mode of influence in which actors’ repeated participation in a social milieu progressively aligns their behaviors with its broadly shared principles, acculturation seems to be precisely what Lara described (and prescribed) as the means for securing compliance with even a formal UN rule.

The similarities here are interesting in part because they suggest that a system of unspoken norms of sociality exists across sites and scales of the United Nations, governing how substantive, codified norms can be enforced.

These rules-for-applying-rules would include the imperative to take “cultural” difference duly into account and to avoid actions that smack of coercion, imposition, or other anti-social behavior. These and related tactics collectively shape what I call the “measured authority” of UN implementation efforts – “measured” not only for being restrained, but also for being calibrated and customized to fit a subject that has been “sussed out” or “taken the measure of.”

Such “measure-taking” is intentionally relativizing. But as we see in Lara’s troublesome conflation of cultural difference and temporal otherness (cf. Fabian 1983), it is susceptible to slipping into universal progress narratives, as well as stereotypes and generalizations like those Miia Halme-Tuomisaari (2013) found in her research on the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Finally, if unspoken norms of sociality temper the regulation of smoking and that of human rights obligations at the UN, it is worth wondering just how extensive the crossover between the two is. After all, despite that both usually take place through interpersonal exchanges, in one case the interlocutor and the subject of regulation match; in the other, they do not. That is to say, states do not smoke; people smoke. It is also people (and not states) who socialize. However, it is states that are obligated by human rights treaties.

For this reason, in my research I have begun inquiring into how notions of interpersonal politeness and propriety influence human rights treaty body members and similarly positioned UN actors (Clark n.d.).

Is it these standards – and not only more formal constraints – that inhibit them from using language that goes beyond “discouraging” or “recommending”? Do agents of human rights regulation feel pressure to avoid being interpersonally anti-social in their official monitoring work? Could it be that some of the “measured authority” in this case too is about not wanting to tell people to their faces when “they” – that is, the states that employ them – are found in contravention of human rights obligations?

Works cited

Clark, Joshua

n.d. Truth Silences: Human Rights Treaty Oversight between Revelation and Relations. Unpublished ms.

Fabian, Johannes

1983 Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Goodman, Ryan, and Derek Jinks

2013 Socializing States: Promoting Human Rights through International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Halme-Tuomisaari, Miia

2013 Contested Representations: Exploring China’s State Report. Journal of Legal Anthropology 1(3):333-59.