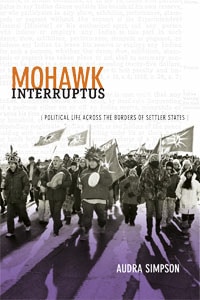

In the online forum Native Appropriations, Dr. Adrienne Keene writes “When you’re invisible in society . . . every representation matters” (Keene 2015). Keene’s need to explore, triangulate and discuss resolutions regarding the need for sovereignty among Native American communities readily matches Audra Simpson’s optimism in her own ethnography, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Like Keene’s blog, Audra Simpson’s writing offers an opportunity to understand how representation manifests itself in terms of both “difference” and “relatedness” (p.11).

To begin with, she reminds readers that political “recognition” places an emphasis on requiring tribes to express a specific version of cultural difference, or “otherness”, instead of an autonomous one, independent from settler and colonial provisions (p.20). In other words, “recognition” still monitors cultural differences in a way that does not lead to equality but rather serves as a reaffirmation of how history has always been reported (p.20, 33). However, Simpson does not dwell on the past, but rather uses it to show how significant the act of “refusal” is among Native American communities, like the Kahnawà:ke, living between the United States and Canada (p.33).

For example, when opposing narratives concerning the heritage of one informant do not merge well together, Simpson wonders, “Why was this exchange so puzzling? Perhaps because a very complicated story has been simplified through history, and this man’s complicated claim does not ‘line up’ with that simple history as easily as we are use to” (p.38). During her interviews, she detects that “the most critical question, the question of family” obscures the promise of having a uniform history for informants living as members among the Kahnawà:ke (p.38). Identity starts with the founding of relationships between individuals of the present and survivors of the past. Without kinship, where is their history?

Though this question poses a worthy challenge to the interviewer, it also represents the extent to how community members have migrated or have gone missing.

At her best, Simpson surprises us because she is willing to start all over again, and reconsider how she defines her terms.

She invites readers to witness the struggle “that challenged an emerging paradigm in my research on the primacy of kinship and family, and family as a political form of relatedness” (p.40). Conflicting legal definitions of family and inheritance further undermine the question of historical representation when she sees how family lines are continually redrawn between the mother’s clan and then rewritten to conform to the pattern of patrilineal descent (p.58).

Simpson clarifies that “My point is not to challenge this interlocutor’s truth claim but to point out the way in which the narrative he provides highlights the very problem of settler colonialism, of fragmentation, of doubt” (p.64). She then discusses the prospect of reinventing ethnographic methodology to better portray this intricate history. To write an ethnography that interrupts assumptions made by anthropologists from previous centuries is also a necessity for advocates seeking to address histories that have disappeared (p.64). In that sense, her strongest point is actually her style of writing, the act of refusing to portray communities as being “more perfect, more culturally ‘intact’” (p.65).

Simpson writes in a way to ensure “a future that is not bound so inextricably to the desires of others” so that anthropologists can evoke more honesty in how they view their own role in documenting history (p.70-71). By constructing a hierarchy of traditions to look for, prior to even interviewing their informants, anthropologists have also contributed to the problem of “ahistoricity”, of neglecting points of views that are not readily “discernable” to those existing outside the cultures in ethnographic studies that were “born, in part, from mimetic play” (p.73, 75, 77). The traditions captured in ethnographies really reflect a tradition of ethnographic methodology that once privileged the anthropologist’s comfort zone by default over the disagreements witnessed during their work (p.73).

Simpson defends the idea that anthropologists should acknowledge the fact that their work consists in creating a meta-critical analysis that always remains messy and unfinished (p.71). In this book, she changes her approach toward ethnographic writing and remains true to her original argument: that one sovereignty can exist within another sovereignty and that this idea “interrupts and casts into question the story that settler states tell about themselves” (p.177). In other words, members within a given Indigenous community may not agree on what representation means to them, yet acknowledging the existence of their debates and discussions is still a way of valuing their “capacities for self-rule” (p.100). One could dispute that all of this theoretical discussion would have fallen on deaf ears if Simpson had chosen not to share it.

Since the work of an anthropologist is never fully complete, when can a researcher start showing their work and analysis in the form of a published ethnography?

I do not see Simpson’s book as lacking information because she “refuses” to complete the stories of her informants (p.113). Rather, it is the responsibility of the reader to learn from more people, like Keene, who encourage members of Indigenous communities to voice their ideas both inside and outside the discipline of cultural anthropology.

References

Keene, Adrienne. “When You’re Invisible, Every Representation Matters: Political Edition.” Native Appropriations. 17 May 2015. Web. 1 Aug. 2015.

**********

Featured image by Pierre Pouliquin (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)