Toronto, summer 2012, three of us having lunch at an Indian restaurant downtown—me and two young Tibetan friends. We were discussing citizenship and asylum for Tibetan refugees in Canada, and yet, like all good conversations, our talk ranged across all sorts of topics: asylum stories, the best Tibetan restaurants in Jameson (aka Parkdale, the neighborhood in southwest Toronto where most Tibetans live), life in Canada as opposed to the US, Tibetan clothes—who wore them and who didn’t and why, the Boudha community in Kathmandu, Tibetan exile politics, Chinese students in Toronto, why Indian food was so heavy (but so good), the new generation of Tibetan activists, and gender, or more specifically, polyandry, a form of marriage in which a woman marries more than one man.

Do Tibetans still practice polyandry? Good question. Do they?

Yes and no. In the Tibetan exile community, which is now 55 years old and thus traverses multiple generations of individuals born inside and outside of Tibet, polyandry is no longer as common as it was before exile (nor is polygyny, when a man has more than one wife). Most marriages in exile are not plural but are monogamous, between two individuals rather than between three, four, or more. Inside Tibet, polyandry’s history under Chinese rule differs, but is currently being revitalized in some places. In the Tibetan refugee community, polyandry exists mostly in the realm of nostalgia and things past.

Contemporary examples of polyandrous marriage appear as exceptions to the norm, as something surprisingly still possible. As a result, the idea of polyandry can seem almost liberatory for empowered young Tibetan women in exile. As my female Tibetan friend proclaimed that day, “I love polyandry, yo. I could do that.”

Could do that. Could fantasize about doing that, but probably would not actually have a polyandrous marriage. Over the last five decades, when Tibetan refugees have talked about preserving their culture, polyandry has not been on the list of things to preserve, to save as a current day practice rather than to treasure as a historic one.

What is the focus of Tibetan cultural preservation in exile? Religion. The arts. Certain visual markers of Tibetan-ness such as a Lhasa-standard chupa, especially as a required style of dress for women. Then again, if polyandry is not on the list of cultural practices to preserve, why is that? Who made the list in the first place?

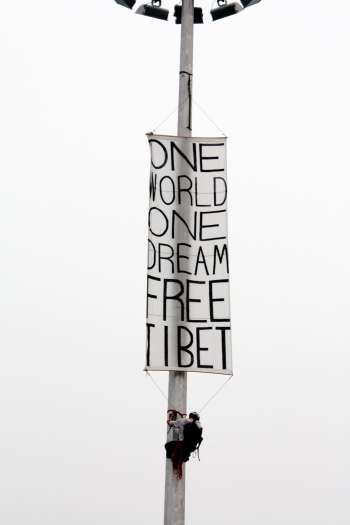

Cultural preservation in exile takes place alongside the political struggle to regain Tibet, be it as an independent country ruled by Tibetans or in some sort of relationship with China. Fifty-five years in exile is a long time. During that period, Tibetan refugees have fought politically for Tibet, have worked to preserve certain cultural practices, and have also created new institutions in their community. Tibetan society in exile is not stagnant, but it is conservative, and thus cultural, political, and religious elites guarded against change in some domains while pursuing it in others. One area of positive change is education.

In the last two decades, a large percentage of Tibetan refugees have moved out of South Asia to other places around the world, but especially to North America. Tibetan youth there attend schools built on cultural, historical, and political traditions different from Tibetan ones. Sometimes these traditions and the logics that undergird them are contrary to Tibetan ideas, sometimes they are complementary to them, and often they are both at once. An example that draws on both new and old thinking about political possibility are current Tibetan practices of “refugee citizenship.”

Refugee citizenship is a Tibetan claim on the world that challenges 20th century conventions of citizenship, in which one can be a refugee or a citizen, but not both. The one category is supposed to cancel the other out.

Indeed, Tibetans in South Asia have long been refugees, but not citizens in both India and Nepal. Although there were various times over the last fifty years when obtaining citizenship was debated in the Tibetan refugee community, the dominant, government-led view was that to take Indian or Nepali citizenship would invalidate Tibetan claims to Tibet.

However, with the mass migration of Tibetans to North America beginning in the mid-1990s and continuing on through today, a new type of refugee citizenship was forged: citizenship in either the US or Canada (or elsewhere in the world, including India) combined with an active refugee identity through the voluntary maintenance of a political relationship with the Tibetan exile government (in the form of the Central Tibetan Administration in Dharamsala). One feature of refugee citizenship has specifically developed in tandem with new forms of communication enabled by the internet—political participation, engagement, and critique. Tibetan exile politics have long been dominated by elites, but there is now a new and dynamic 21st century grassroots participation in political life.

This is a cross-generational phenomenon, yet some of the most powerful voices belong to the younger generation. From the posts on Lhakar Diaries, to heated discussions on Tibetan-language sites, to organizing and educating on Facebook and other online spaces, Tibetan political debate and action has a new and fresh energy. One example of this is the conversation taking place around an article posted online in early October 2014 by Kasur Lodi Gyari Gyaltsen, an accomplished and influential Tibetan politician, former speaker of the Tibetan Parliament, former Cabinet Minister, and for over two decades, the Special Envoy of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and chief negotiator in Tibetan-Chinese political negotiations from 2002-2012. (Full disclosure: he was also my mentor at the International Campaign for Tibet in Washington DC in 1992-1993, before I began graduate studies in anthropology and history at the University of Michigan in the fall of 1993.) As politically and historically important as his article is, what struck me as just as telling for the Tibetan exile community were the almost immediate responses that appeared online, chief among them an eloquent essay by two young Tibetan women in Switzerland—Migmar Dolma and Tenzin Kelden.

Their two prime messages are political participation and the allowance for differences of opinion. They write in a bold, yet respectful tone, one that acknowledges existing hierarchies and expectations for behavior in the community and yet that insists these hierarchies and expectations be open to review and discussion, if not critique. They exemplify the in-between political sensibilities of refugee citizenship. In their own words:

“At the same time, we appreciate the confidence placed in us, as the younger generation, regarding our thoughts and ideas for Tibet. We always felt that there is a genuine mutual respect and appreciation regardless of any kind of differences.”

“Last but not least we would like to stress that we, like Lodi Gyari, are deeply grateful for the guidance and leadership of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. It is very clear to us that His Holiness’ tireless efforts have brought great achievements for the Tibetan Movement and our community in exile.”

“Different opinions can and should occur on any topic. Having had the opportunity to enjoy education in the West, we grew up learning to form our own opinions. Whether it was reading a book or scientific papers – we were always challenged by our teachers and professors to analyse and then comment on what we had in front of us. Active individual participation was always required by our teachers.”

“True unity of people is when there is room for acceptance of difference for different opinions and an open discussion.”

These excerpts give a sense of their essay, its content and its tone, and their claim to participate in the shape and direction of Tibetan political futures. These futures are also cultural, for their essay is not just about the political but also about community in general, about the right to speak and be heard, to make new claims for new times and yet to ground their claims in Tibetan sensibilities. As they write:

“We often hear words like “preservation” or “continuation”. Of course, we preserve what has been given to us. But that does not mean that we cannot bring in new ideas, new forms of cultural or ideological expressions that are reflections of present circumstances. In this process, there needs to be an exchange between generations at eye level and without patronisation. This kind of exchange can only be beneficial for every society.”

The conversation Migmar Dolma and Tenzin Kelden seek to open in their essay is an already ongoing one. In important ways, it is a conversation Kasur Lodi Gyari Gyaltsen was instrumental in starting as one of four founders of the Tibetan Youth Congress in the 1960s, and one that his service over the years has made possible. And in other ways, this is a new conversation, started by a new generation for the 21st century.

This is a generation that “loves” polyandry, but is socially and politically focused on other public issues. This is a generation that is speaking out on sexual violence, that is taking on issues of rape and domestic violence in ways not seen before in the exile community.

This is a generation fluent in multiple cultural and political idioms, committed to both preservation and transformation, to acknowledging that preservation was ever only a partial project, and to recognizing and acting on those ideas and practices which need to be transformed or reclaimed or both.

As for polyandry, perhaps the time has come for it to make the same sort of comeback in exile that it has in Tibet. Perhaps this comeback is already underway. The possibilities of citizenship are never only about the political, and refugee citizenship is no different in that regard. The social, the cultural, and the historical all matter.

Polyandry? You could do that.

Thank you very much for your article. A friend of mine sent me an article in Russian “Polyandry in Tibet” and I decided to find English sources that would support this fact. Your article was one of them that came up in Google when I used the following search words: “marriage tibetan style” (there is an old Italian movie with Sophie Loren Marriage Italian Style).

All the best to you!

Lola