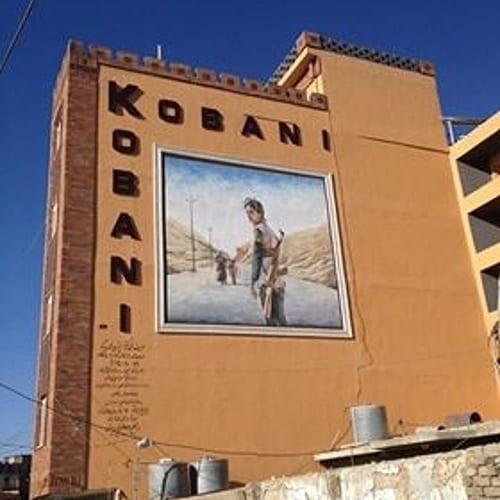

It was during my fieldwork in Slemani, Iraqi Kurdistan, when I started seeing Kobane popping up everywhere in the city. Hair salons, murals, restaurants, travel agencies and even newborn babies were being named after the small city in Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan). Famous for its liberation from ISIS (DAESH), for which Kurdish forces had fought for months back in 2015, Kobane had become elevated into a new symbol of hope and resistance. What resonated even more with me was when a new bridge, connecting the northern ring road in Slemani, was named “Kobane Bridge”. At the time I was shooting a film about Mihemed, a Kurdish Syrian journalist from Kobane himself, who was living as a refugee in Iraqi Kurdistan. All at once my research had come together; future imaginaries, infrastructure and state building, Kurdish independence and migration — but how to connect them in film? In this contribution, I aim to engage with how visual methods can help develop ethnographic skills and advance how we ‘understand our past, how we engage with our present and how we imagine our future.’ (Pink 2009: 3). How do people envisage their future and how can they find agency to enact or plan for these horizons under precarious conditions and ever shifting contexts?

Can visual research methods offer a way to capture the invisibility of temporality and future imaginations?

This paper will consider the visual and theoretical approaches to exploring how people in Iraqi Kurdistan re-negotiate their future plans in times of crisis through discussing the ethnographic documentary film Bridge to Kobane.

“Sometimes I wake up and think it was all a dream, I wish it was. You cannot make a plan because new things keep happening. I have to wait, maybe go to Europe or Australia. No one, even DAESH (ISIS), America and those forces here do not know what will happen.”

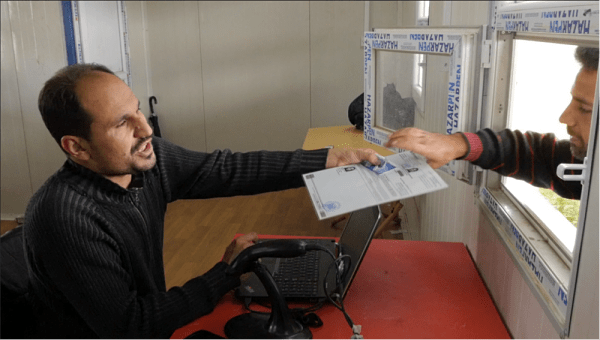

Mihemed was stirring into a small pot with coffee in the kitchen of the NGO office he was working. As the froth was accumulating on the surface, he started moving the pot up and down until he was satisfied and poured the coffee into two cups. I had met Mihemed while I was following the work of a French NGO in charge of the food distribution in the refugee camps around Slemani. After some initial conversations about his work, Mihemed showed interest in working on a film project together. We decided on several scenes and locations for interviews, and I continued to visit him and his family during my fieldwork period.

Mihemed working for the food distribution in the refugee camps. Screenshot Bridge to Kobane (2016).

Mihemed and his family fled from Syria a few years ago, after they had moved from Sham (Damascus), to Haleb (Aleppo) and back to Kobane, until they fled across the border into Iraqi Kurdistan when the fight against ISIS intensified. In Iraqi Kurdistan he first worked as a journalist. However, when the economic crisis hit in 2015 and governmental cuts started affecting the economy at large, he started working for an NGO in order to support his children and parents, who were also in Slemani. Still active in his network, he continued to report on the situation in Syrian Kurdistan and attended conferences and meetings with fellow journalists. In 2016, Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan) declared their autonomy from Syria, which was welcomed in solidarity by locals and Syrian Kurds in Iraqi Kurdistan. Although the political ties between the different political parties across the two regions fluctuate in a struggle for power, the name of Kobane resonated deep across the Kurdish population.

Bridge to Kobane tells the story of Mihemed, who, despite the liberation, cannot return to Kobane due to the on-going war in Syria.

Connecting the Kobane bridge in Slemani to Mihemed’s longing for a return to his hometown, the documentary film explores themes of mobility, death and ever shifting future horizons in connection to cross-border perceptions of the Kurdish nation. Here, Kobane as the critical event (Das, 1995) or ‘generative moment’ (Meinert and Kapferer, 2015) is linked to the Kurdish political imaginary and re-negotiated through home-making practices, creating interplay between time and future horizons through the use of montage.

Building Kobane bridge in Slemani. Screenshot Bridge to Kobane (2016).

The contribution of visual media in anthropology and ethnographic films has been acknowledged to be ethnographically descriptive and committed to participant observation (Taylor 1998: 537; Cox and Wright 2012: 11), the camera argued as an extension of the ethnographic gaze (Crawford and Turton 1992: 18). Film as ethnography has since thought to open space for issues of representation by involving them in the filming and editing decision making process (MacDougall 1998; Pink 2001). The importance of the visual lies in the capacity of images to make a direct appeal to the senses through its assemblage, manifested through the illusion of presence rather than its direct illustration (MacDougall 2006; Cox and Wright 2012: 118). This relational and sensorial aspect is however not only created through the observational approach that the camera can capture. The strength of visual anthropology lies into the combination of the visual and text. Rather than conforming to a text/image divide put forward by anthropologists (Banks and Morphy 1997), Cox and Wright argue that visual anthropology can offer new ways of knowing and representing in social research through the convergence of the two (2012: 126).

In the observational style in ethnographic films, semi-structured interviews are placed in the process of daily activities and rituals, the embodied practice undertaken through a handheld camera allow for different engagements between the ethnographer and the informant (Henley 2006; MacDougall 2006). Considering then the reflexive moment about the ethnographic task (Clifford and Marcus 1986) not as merely textual, it also gave way to the spread of more phenomenological approaches (Jackson 1989), sensuous scholarship (Stoller 2010), sensory approaches (Taussig 1993; MacDougall 2006) and corporal engagements (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2009). Thus observational cinema can be seen “a point of departure into anthropological inquiry” rather than an end (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2009: 138). Informed by the observational method, I set out to film Mihemed in his daily routine, the presence of the camera evoking reflections on his current situation as a refugee. Mihemed and I decided on the places we thought necessary to include. Over the course of the next 9 months we continued to capture some moments of Mihemed’s life in these spaces.

Film arguably opens an active space for reflection through which we obtain an insight into the subject’s world, where we can begin to relate to aspects of their experience and imagine further implications (Grimshaw and Ravetz, 2009: 121; Henley, 2004: 114). Visual research and filmic ethnographies then inform us about drawing relations between themes and narratives, rather than generalisation. This makes it possible for the researcher to open an active space by allowing viewers to draw their own connections and inform about particular ways of social knowledge perhaps not easily communicated through written word (MacDougall, 2006). My research focused on imaginaries of the future and how the shifting horizons of the yet-to-be were re-negotiated by people in Slemani. In Mihemed’s case, migration became an important issue, not unknown to Kurds who have been subjected to multiple and multifaceted ways of migration across the 4 nation-states of existence (Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey).

How to show these changing plans of and for the future ethnographically through film?

Film editing is believed not to impose ideas from the outside, but to discern resonances within the rushes (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2009: 118). Thus, editing and montage becomes another tool within using visual methods and the output format. In ‘Transcultural Montage’ Suhr and Willerslev argue for montage as an amplifier of invisibility (2013). By using montage to present a certain absence or invisibility through disrupting the normative space of film, we see through its absence something that cannot be understood otherwise (Ibid: 6). They put forward that montage as an analytic offers not only the link between the experienced and the imaginary, what Irving has called the ability to capture the fractured and fracturing nature of human sense perception (2013: 105), but also works, as ritual, to show the multiple perspectives and interpretation that are continuously shaping our consciousness and experience (Suhr and Willerslev 2013: 11).

Film has been discussed as a powerful tool in dealing with capturing invisibilities, dream, futures, past and continuous changing in self-perception and self-becoming (MacDougall 1998; 2006; Kristeva in MacDougall 1998: 274). Irving proposes that montage in film works to inform the research not only as a method of filming on site, but also as an output that can allude to how people experience wholeness through different senses; it creates a reality as an experience that is not fragmented but manifests itself as coherent (2010, 2013). It is then here where transformative moments, such as imaginative horizons (Crapanzano 2004), can be explored through film as its fragmentary and transitory nature and how different realities shaped through different senses and experiences can destabilize and juxtapose conflicting realities (Irving 2013). Montage then opens new possibilities for open-endedness; allowing audiences to be able to engage with the different connections and juxtapositions in the visual narrative.

The visual methodology thus allows engaging with how different life paths are imagined and reflected upon by informants.

I understand observational cinema and montage as a method of incorporating different embodied strategies and tools in order to collect ethnographic data. For example, a scene where the call to prayer evoked childhood memories to Mihemed is juxtaposed with the next scene, where these memories intertwine with his wishes for return or new migration, a future unattainable through border restraints. With the borders to Europe closed, the Turkey deal in place and his visa to Australia on hold, Mihemed has to opt for new ways of offering his family a better life. Over summer he helped his brother and sister-in-law to cross from Kobane over to Slemani, for the reason that their house in Kobane continued to be in ruins, the scarcity of work and food, and the unbearable wait for a never-ending war.

Cutting between Mihemed’s narrations about what he considers Kurdistan, which shifts between only comprising Iraqi Kurdistan and at other times the wider Kurdistan region, with the communal narratives brought forward in a scene capturing a political rally, we can begin to relate different perspectives and imaginaries on what constitutes Kurdistan and the Kurdish nation.

The reflection of different life paths and futures becomes vividly visible in the final scene where Mihemed and his family go to visit the grave of his mother who passed away suddenly. “Kurdistan became her graveyard” Mihemed says. The realisation that his mother, despite escaping the cruelties of ISIS, found her final resting point in Iraqi Kurdistan links back to the slowly shaping and cutting off of different imagined life paths. Perhaps one of renegotiating to settle in Iraqi Kurdistan through home-making and ritual, exemplified in the scene where the same concrete breezeblocks are used to build a new house, but also to make a grave. Using the camera as a catalyser in this scene, Mihemed slowly reveals his reflections on the sudden death of his mother. Through cutting these narrations with the pouring of water over the grave, part ritual and part play with his children, the audience can envision both the paths closing and opening in Mihemed life as the film ends.

Through a discussion of the visual methods used in Bridge to Kobane I aim to show that through montage and long-term observational film, we can open up a space to explore shifting future horizons and possible futures, leading to an understanding of how people renegotiate plans during times of crisis.

“We don’t know what will come in the future… we have to drink a Syrian coffee to look and tell the future from the coffee grounds”

Back in time in the NGO kitchen Mihemed’s smile showed traces of happier times, as he made sure that both cups contained the same amount of froth. “It is where the luck is”.

Bibliography

Banks, M., and Morphy H. (1997). Rethinking Visual Anthropology, New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Clifford, J., & Marcus, G. E. (1986). Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography. Univ of California Press.

Cox, R., & Wright, C. (2012). Blurred visions: Reflecting visual anthropology. FARDON, R; HARRIS, T; MARCHAND, M; NUTTALL, WILSON, A.(Org.). The SAGE handbook of social anthropology. London: SAGE Publications, 84-101.

Crapanzano, V. (2004). Imaginative horizons: An essay in literary-philosophical anthropology. University of Chicago press.

Crawford, P., and Turton, D. (ed.) (1992) Film as Ethnography. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Das, V. (1995). Critical events (p. 55). Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Grimshaw, A., and Ravetz, A. (2009). Observational Cinema: Anthropology, Film, and the Exploration of Social Life, Indiana University Press.

Henley, P. (2004). Putting film to work: observational cinema as practical ethnography. Working images: visual research and representation in ethnography, 109-130.

Henley, P. (2006). Narratives: The Guilty Secret of Ethnographic Film‐Making?. Reflecting Visual Ethnography: Using the Camera in Anthropological Research, (145), 376.

Irving, A. (2010). Money, Materiality, and the Imagination: Life on the Other Side of Value. Human Nature as Capacity: An Ethnographic Approach. N. Rapport, ed, 130-153.

Irving, A. (2013). Into the gloaming: A montage of the senses. Transcultural montage. Oxford: Berghahn.

Jackson, M. (1989). Paths Toward a Clearing Radical Empiricism and Ethnographic Inquiry.

MacDougall, D. (2006). The Corporeal Image, film, ethnography, and the senses, Princeton University Press.

MacDougall, D., & Taylor, L. (1998). Transcultural cinema. Princeton University Press.

Meinert, L., & Kapferer, B. (Eds.). (2015). In the Event: Toward an Anthropology of Generic Moments. Berghahn Books.

Pink, S. (2001). Doing ethnography: Images, media and representation in research. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3 (1).

Pink, S. (2009). Visual interventions: Applied visual anthropology (Vol. 4). Berghahn Books.

Stoller, P. (2010). Sensuous scholarship. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Suhr, C., & Willerslev, R. (Eds.). (2013). Transcultural montage. Berghahn Books.

Taussig, M. T. (1993). Mimesis and alterity: A particular history of the senses. Psychology Press.

Taylor, L. (1998). Visual anthropology is dead, long live visual anthropology!. American Anthropologist, 100(2), 534-237.

Filmography

Askari, L. (Director). (2016) Bridge to Kobane [Documentary]. United Kingdom: Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology