There is a mythology of nourishment deposited in the language of the intellect.[1] Thoughts are digested. Ideas are chewed upon. There is hunger for information and a thirst for knowledge. Those who traffic in ideas like academics, are hence something akin to gardeners, tending the ground to yield provisions through which they sustain themselves and each other.

For an increasing chorus however, academia has been swept into a mode of production which is doing something else. It is a mode which commoditizes pedagogy and research (Collini 2010), which produces a reserve army of post-doctorates primed for a narrow pool of positions (PrecAnthro, Thorkelson, this issue), and which privileges accounting practices over quality and content (Strathern 2000), and thus continually driving towards the production of surplus (2016). For Michael Taussig, the academic garden has now become an ‘agribusiness’ (2015) – with its own peculiar way of writing.

Somehow it makes sense then that one of the pushbacks to such developments has its origins in the Slow Food movement. With its basis in Italian rituals of commensality and artisanal food production, and its open foe to the behemoths of corporate globalization, Slow Food has offered a political and metaphorical model against the advance of academic agribusiness. Indeed this publisher – Allegra Lab – was founded three years ago with an evocative ‘Slow Food Manifesto’. More recently, American scholars Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber have penned their own ‘Slow Professor Manifesto’ (2016) – drawing on the same conceptual roots. Berg and Seeber’s diagnosis is simple: the circumstances challenging many working academics can be encompassed by a culture of oppressive acceleration. The cure then becomes equally so: ‘a slow approach to teaching and learning’ (2013:1) to disrupt the corporate ethos of speeding up.

Slowing down is certainly one option. Yet if there is one thing we learn as ethnographers, it is that there are many ways of responding to the exigencies of a given system.

This thematic section – Ethnographies of Academia – is hence intended as a critical inquiry into how academics are variously processing their workplaces now.

In the process, we hope to initiate some means of exit from the sometimes circular discussions around the neoliberal university (Giroux 2014). Instead, our focus is on how academics themselves are reproducing or questioning contemporary values and norms.

The aggregate speaks to an intriguing dichotomy within academia itself, between the passionately political and the steadfastly not. At one end of the spectrum, Tim Ingold and PrecAnthro present two solidarity projects with different but overlapping goals. Ingold and his colleagues are striving to ‘Reclaim the University’ of Aberdeen from auditors and managers by substituting critique for a positive mission. They have collected a manifesto in which they outline four pillars which define a university’s purpose – freedom, trust, education, and community – and hope to have these adopted by the university as guidelines for its future. Such a project carries Ingold and his allies into unchartered waters, and the progress of their efforts will no doubt be instructive for scholars in the UK and elsewhere in the months and years to come. PrecAnthro, meanwhile, seek to turn the reserve army of postdoctorates into a collective force which can be mobilized to improve their working conditions. Again, PrecAnthro are attempting something without precedent. If successful, such a union would create new political alliances among junior scholars which could transform academic relations within and between universities and regions.

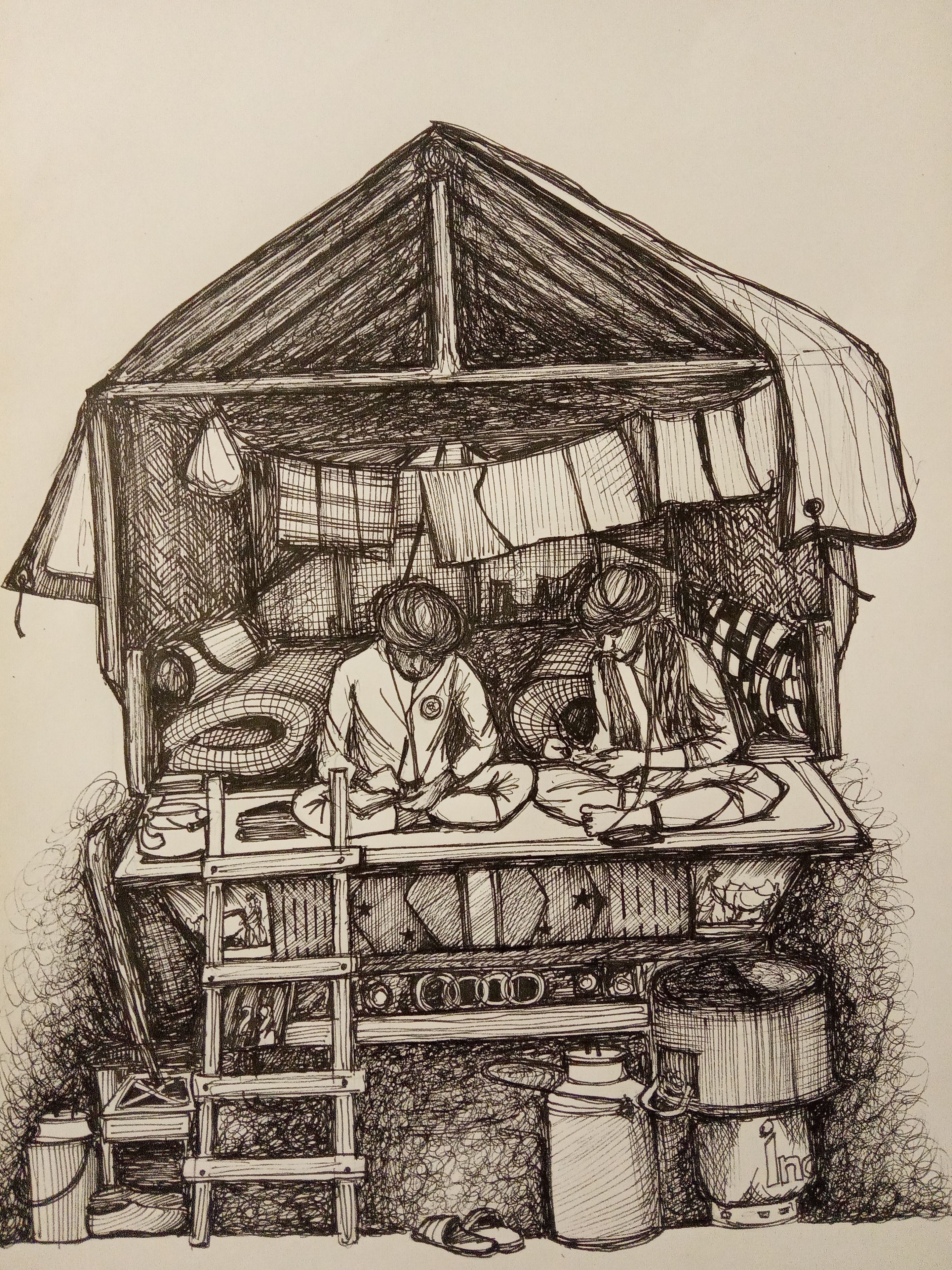

Photo by Carlos G. Casares (flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Marta Pérez and Ainhoa Montoya by contrast, offer a diagnostic perspective on academic precarity. They argue that scholars can culturally reproduce precarious labour contracts by extending their reach through what they call ‘chains of precarity’. Such concatenation occurs when this labour situation starts to deleteriously effect a whole range of social relationships: with students, research participants, written work, but also by implication with friends and family members. In calling for a collective undoing of these chains, they reinforce the solidarity project presented by PrecAnthro.

Eli Thorkelson’s essay instead offers an example of the schismogenesis that this situation can produce. A consequence of expanding precariatization, he argues, may be to denaturalize some of the values which currently sustain academic hierarchies: one of them being the intellectual as hero. In free-form discussion with one of his research participants – a graduate student in France – the latter presents a personal philosophy of anti-heroism. Thorkelson speculates that perhaps this is a survival tactic when becoming a hero oneself becomes an ever more remote possibility.

Ian Lowrie’s account of Russian Data Scientists adds a valuable alternative to this engagement with Europe. His narrative echoes Thorkelson’s to the extent that values which once sustained academic hierarchies are being questioned and displaced; yet the result is rather different. This vanguard of young Russian reformists are embracing techniques which have been the object of derision elsewhere – audit culture and self-management – because they present an appealing liberation from the dominant patronage system. Critically, however, one thing they are not embracing is precarity – all being securely employed. Are the changes in academia more palatable when precariatization is not one of them?

Finally, Hoda Bandeh-Ahmadi renders a thought-provoking analysis of the character of academic relations in general. She encounters frequent recourse to idioms of kinship as her interlocutors in Indian social science departments describe one another. It might be added that this is kinship of a very specific kind – genealogical kinship – meaning that it is continually vertical relationships between doctoral supervisors and their students, rather than alliances which really count here. For the purposes of this discussion Bandeh-Ahmadi’s research then poses a vital question – does intellectual kinship actively work against the rupture that political action sometimes requires?

Although the publication of this section evidently expresses tacit support for the projects of reclaiming the university and transnational labour organizing, it equally seeks to open up more perplexing questions around the robust refusal of dissent among academics, even in the face of exploitative conditions. Yet whether academics are able to mobilise politically or not – one thing remains likely.

If we are to thrive rather than simply survive in the twenty-first century, we must somehow retain our role as gardeners producing food for thought, rather than for sale by those who profit from academic agribusiness.

Bibliography

Berg, Maggie, and Barbara Seeber. 2013. “The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy.” Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal 6 (3): 1–7.

———. 2016. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Collini, Stefan. 2010. “Browne’s Gamble.” London Review of Books, November 4.

Giroux, Henry. 2014. Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education. Chicago, Ill: Haymarket Books.

Lattier, Daniel. 2016. “Why Profs Are Spending So Much Time Writing Crap That Nobody Reads.” Intellectual Takeout.

Strathern, Marilyn. 2000. Audit Culture: Anthropological Studies of Accoundatbility, Ethics, and the Academy. London: Routledge.

Taussig, Michael T. 2015. The Corn Wolf. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 2016 (1931). The Mythology in Our Language. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

[1] See Wittgenstein (1931).

Dear Vita

Reading your post gives/makes me ‘allegroa’ (my ‘Eurasian slow cooking’ daughter lives in Italy).

A voice from outside the academia in The Netherlands. I am a ‘clinical-systemic’ anthropologist publishing mostly in non-anthropological journals and handbooks. Increasingly with non-anthropological co-authors.

Among other stuff I co-educated transcultural family therapists in Amsterdam. One major methodological thread in their work is to learn to find, and to listen to, voices least heard in the social systems (families/communities) they guide. For us anthropologists, I think, this rings a bell.

I have many, anthropological and other, contacts/friends in the academia but could never make it there beside some guest lectures every year. What I missed is exactly why I stayed, after graduating in 1988, outside the academia.

The battle you, as anthropologists, fight from within the academia gives me hope while I quit my (4 years) PhD project three years ago at 65. The passion I cherished for decades in working/publishing as a clinical anthropologist with young men and their families was slowly but definitely killed. Not just by my doctoral advisor but by the ‘doxic’ sterilized system, of which you and hyperlinked co-authors try to unravel.

But there are voices least heard somewhere in your thematic thread. Are you (the reserve army of post-doctorates) ‘prisoners of your own device’ (Hotel California)? Are you, just like any member of any cultural/ethnic/indigenous group, part of a social system which leaves you with a particular, but rather limited, agency?

What I miss in a lot of academic knowledge producing stuff are the ‘parallel (reflexive) processes’ between the peoples/systems/meanings we study and your own, badly paid but still privileged (??), lives in universities as (Batesonian) ‘runaway’ systems.

Paul Simon sang in 1986: …Well, it’s not just me. And it’s not just you. This is all around the world…

Our ‘anthropological archives’ (of 140 years of ethnographies) are overloaded with applicable insights and BOKSes (Bodies Of Knowledges and Skills) for problems in our urbanized societies. Waiting to be ‘translated’.

Including ways to understand/heal our schismogenic academic systems.

I earned my money, as a clinical anthropologist/social entrepreneur for almost thirty-five years, by translating some of these insights towards maturing young men multicultural contexts. Outside the academia. http://www.anthropo-gazing.nl

…protecting and tuning my ‘talmudic craving’… wanting to understand…

…free at last…

thank you for your efforts

Dirck van Bekkum

PS Andreas Weber, as one of the forerunners, in his enlivement/biopoetics publications is coming closer and closer to re-connect biology with anthropology.