The study of bureaucracy has become a standard prerogative of English-language anthropology in recent years. Long gone are the days when bureaucracy was considered the exclusive realm of political scientists and sociologists, in an intellectual division of labour where anthropology was assumed to be the study of “non-bureaucratic societies”. In addition to the anthropologists who have become centrally concerned with public bureaucracies (Matthew Hull, Laura Bear, Nayanika Mathur, Akhil Gupta, Colin Hoag, David Graeber to name a few), others have encountered the subject through a separate route, often in the form of paperwork circulating among their interlocutors or discourses reproduced about “the state” and its nebulous operations. The growing anthropological interest in bureaucracy might be a sign of our own times as Graeber argues, yet it is also a knowledge-making project with implications beyond the bounds of social anthropology, whether in other disciplines or in the wider public.

With this context in mind, I have convened a seminar series at Oxford this winter term to gather ethnographers who have conducted fieldwork on different bureaucratic sites, in areas ranging from Jordan to France to Cameroon to the United States. There was no common thread in the selection of presentations other than this interest in the ethnography of bureaucracy, and contributions were elicited with the intention of diversifying case studies and approaches to the subject – including perspectives from gender and sexuality studies, linguistic anthropology, political theory, and science and technology studies.

Despite the range of presentations, the seminars addressed common themes concerning the gap between bureaucratic ideals and practices, the ethical dimensions of bureaucratic work, and the materiality and affectivity of paperwork (including in its digitized guise).

This report is an attempt to gather these common threads together while highlighting the individual contributions made by each paper, most of which await publication. The seminar series was held in Christ Church and supported by the Christ Church Research Centre.

Eda Pepi started off the series with a paper on family registers in Jordan. A seemingly innocuous document where citizens record their family ties, the register has become a contested site for the redefinition of what constitutes Jordanian citizenship. With historical and ethnographic erudition, Pepi explained how Jordan’s gendered and racist citizenship laws, where male Jordanians with a “non-Jordanian” father and especially those of Palestinian descent are always liable to be denationalized, are negotiated by Jordanian women who seek to register their male kin to ensure that they will not arbitrarily lose their rights. Without being able to pass on citizenship on their own, Jordanian women navigate the constraints imposed by state institutions on their kin’s ability to access state services and own property via unexpected uses of a personal registration document comparable to a state-sanctioned family tree, which has become in effect a more potent proof of identity than national passports.

Michael Prentice gave a paper attempting to answer a simple question: what is a corporation? Based on fieldwork in a South Korean firm, Prentice complicated the idea that the corporation is a single agency acting with a common and united will, because it is in fact a set of cooperating groups with legal and hierarchical ties that are not necessarily unified in everyday operations. With attention to the daily work conducted by the Human Resources and Public Relations division within his firm, Prentice showed how the corporation’s power to act is not always unilaterally exercised from the top, but can also be constrained by the different types of expertise handled by various divisions within the corporation. This expertise shapes different expectations about the nature of the corporation itself and thereby allows expert actors to reframe and redefine what can be decided on behalf of “the corporation” by higher-level decision-makers. The broader issue raised by Prentice was the extent to which corporations and state bureaucracies, two social forms that are traditionally deemed distinct, can be compared based on this kind of relationship between expert knowledge and hierarchical authority.

José-María Muñoz gave a detailed account of the regulation of terrestrial freight transportation between Cameroon and Chad, specifically in the Douala-N’djamena corridor. Based on extensive fieldwork within the Cameroonian National Freight Bureau (BGFT) as well as among truckers manning the freight trade, Muñoz described the successive changes to the bureau’s administration and regulations, including material changes in paperwork going up to recent attempts at digitization. The presentation neatly illustrated how paperwork never really disappears or “dematerializes” in the bureau’s work, as according to the dominant ideology circulated by modernizing elites nationally and internationally, but is rather rematerialized by accommodating existing paper-based arrangements with new practices of digital control over them. Muñoz’s intervention is an excellent illustration of relative successes and failures in a transition to digital administration where the “heaviness” (pesanteur) of paper-based practices is what allows bureaucratic regulation to remain effective under conditions where it is deemed to be hindered by these very practices.

Seamus Montgomery presented on his fieldwork among European Union bureaucrats under the Juncker commission. Montgomery became interested in Juncker’s announced project to create “a more political administration” in Brussels, which brought his interlocutors to reflect on the central tension between their professional image as neutral “technocrats” and what some of them perceived as an undue simplification of their bureaucratic work in an era marked by populist politics, from the Greek crisis to Brexit. Montgomery’s broader project is to understand how bureaucrats attempt to craft a pan-European identity and how they deal with the inherent difficulties in pinning down what this “Europeanness” means in practice – especially under circumstances where each bureaucrat was socialized by national-level institutions. His paper highlighted the importance of taking seriously what bureaucrats think and say about themselves, and what we can learn about their process of identity formation in so doing.

Bernardo Zacka gave a paper about informal taxonomies on the front lines of welfare service provision in a large city in the Northeast United States. A political theorist by training, Zacka became interested in what the bureaucrat’s ways of classifying different clients and their problems can tell us about democratic accountability and justice in the provision of services to the citizenry. Zacka concluded that while the discretion allowed to bureaucrats in the exercise of their profession is difficult to monitor according to a stringent abstract standard of democracy, their moral labour is still imperative to the everyday functioning of state institutions. This labour allows them, among other things, to develop self-justifications about the conduct of their work under conditions where the needs of all clients cannot possibly be satisfied, given an underfinanced and understaffed administration. Zacka’s argument is detailed in more depth in his recent book, When the State Meets the Street.

Julie Billaud presented on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in Geneva, an official monitoring process within the United Nations human rights system instituted to give all UN member states some feedbacks on their human rights record by fellow nations. With great attention to the work of interns within the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights – including the anthropologist herself – in compiling comprehensive “country reports” about each participating delegation, Billaud highlighted the opportunities and constraints afforded to civil society organizations by a formulaic reporting process in order to ascertain human rights violations. The voices of all stakeholders are mediated by rigid linguistic rules, endless streams of paper, rigorous administrative procedures, and international civil servants working within the United Nations. With echoes from Zacka’s paper, Billaud highlighted the importance of the bureaucrat’s ethical labour, with an added attention to the material mediations in the bureaucratic process itself, emphasizing the invisible technical skills and affective labour behind the crafting of depersonalized documents.

Marie Alauzen gave a final talk on recent efforts to modernize online state administration in France, based on a case study dealing with the design and implementation of a platform called “FranceConnect”. Inspired by Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) allowing users on any third-party website to verify their identity by logging via Facebook or Google for example, FranceConnect allows clients to access all administrative websites at once without logging in with separate credentials registered with different institutions each time. With a strong grounding in recent works on the state in French science and technology studies (e.g. Muniesa & Linhardt 2009, Linhardt 2012), Alauzen explained how FranceConnect’s emergence can be understood as a “trial for the state”, a moment where the state’s very existence – in this case, its online control over user identities – is put in question until it reacts through certain socio-technical arrangements and becomes describable in the process. In addition to its theoretical depth, Alauzen’s presentation was a sobering reminder of the importance of engaging with scholarship beyond the English-speaking world, not least because it enriches existing conversations about the anthropology of bureaucracy in Anglo-American circles with novel case studies and theoretical insights (see, e.g., Muzzopappa & Villalta 2011, Ferreira & Nadai 2015).

Nayanika Mathur was scheduled to give a talk developing some key points in her recent prize-winning monograph, Paper Tiger, but it was cancelled due to the ongoing University and College Union (UCU) strike over announced pension cuts to the University Superannuation Scheme (USS) in the United Kingdom. This unexpected ending to the seminar series is a fitting reminder that the bureaucratic structures of governance examined by anthropologists all over the world bear similarities to the ones managing the anthropologist’s own workplaces. The muddle generated by the cuts and ensuing strike acts as an invitation to clarify the ways in which university bureaucracies impact scholarly work and constrain knowledge production. An anthropology of bureaucracy that does not engage in this work of clarification and comparison will risk establishing exceptions where there might be, in effect, common mechanisms of authority and control.

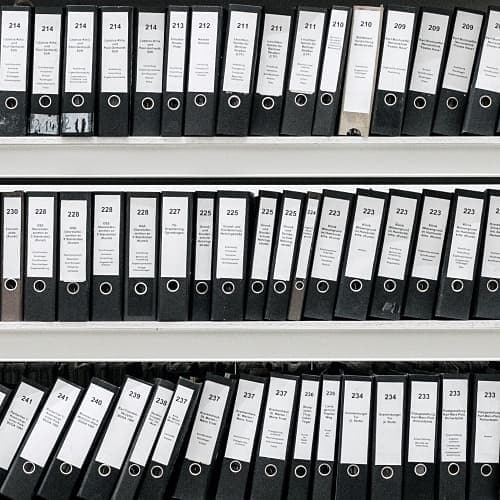

Featured image (cropped) by Samuel Zeller (unsplash.com)

References

De Mesquita Ferreira, Letícia Carvalho & Larissa Nadai. 2015. Reflexões sobre burocracia e documentos: Apresentação de dossiê. [Reflections on bureaucracy and documents: A presentation of the special issue, in Portuguese] Confluências: Revista Interdisciplinar de Sociologia e Direitos, 17 (3): 7-13.

Linhardt, Dominique. 2012. Avant-propos: Épreuves d’État. [Preface: Trials for the State, in French] Quaderni : Communication, technologies, pouvoir, 78 : 5-22.

Mathur, Nayanika. 2016. Paper Tiger: Law, Bureaucracy, and the Developmental State in Himalayan India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Muniesa, Fabian & Dominique Linhardt. 2009. At Stake with Implementation: Trials of Explicitness in the Description of the State. CSI Working Papers, 15.

Muzzopappa, Eva & Carla Villalta. (2011). Los documentos como campo: Reflexiones teórico-metodológicas sobre un enfoque etnográfico de archivos y documentos estatales. [Documents as a field site: Theoretical and methodological reflections on an ethnographic focus on archives and state documents, in Spanish] Revista Colombiana de Antropología, 47 (1): 13-42.

Zacka, Bernardo. 2017. When the State Meets the Street: Public Service and Moral Agency. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

This is a very welcome contribution as indeed, anthropologists, have strangely shied away, until fairly recently, from the study of bureaucracy. They have not only, as Quarles van Ufford (1988) said a long time ago, “refused to wear pin stripe suites” (e.g., study those in power), but also haven not taken seriously what bureaucrats think and do (which is different from ‘critiquing’ them). In this respect, I do hope that the statement that “the study of bureaucracy has become a standard prerogative of English-language anthropology in recent years” is not overly optimistic – as far as I can see the number of people practising this interest is still very limited, ever since Handelman and Leyton (1978) and Lipsky (1980; a political scientist!) initiated the ethnography of bureaucracy in the 1980s, a field where a seminal author like Heyman (1995) was for a long time on his own.

This neglect seems particularly strange as the study of organizations in the 1920s was actually initiated by anthropologists – who quickly discovered that there is ALWAYS a gap between bureaucratic ideals and practices. So such a finding should not be listed under the heading of new discoveries, nor should that be done with a research result that large-scale organizations are heterogeneous phenomena. Sociological institutionalism (Meyer and Rowan 1991) has demonstrated that quite a while ago and theorized it with the concept of ‘loose coupling’ (Weick 1976), while policy studies since the 1980s have shown that implementation ALWAYS goes into unplanned directions, and “How great expectations in Washington are dashed in Oakland; Or why it is amazing that (any policy) works at all” (Pressman and Wildavsky 1973). And there are sociologists who have produced interesting work on the ethics of bureaucracy and the bureaucrat, starting with Max Weber and including for example Hilbert (1987) and Osborne (1994); I do agree that this is an interesting field and more could be done here. But some interdisciplinary looking right and left, including to the history of bureaucracy, would certainly do no harm – even if we have to acknowledge that altogether, our sister discipline of sociology has been surprisingly passive in the field. Where interactionist sociology has been active, way ahead of anthropology, was in the ethnographic study of (semi-)professionals, like policemen (Bittner 1967), or medical personnel (Becker et al. 1961; Freidson 1970) – a field which produced some very important French-language contributions (e.g. Monjardet 1994, 1996; see also Crozier 1963).

Maybe this aversion of anthropologists to epistemologically siding with the bureaucrat, e.g. taking him/her as the native, might be an effect of the genetic imprint on the discipline which up to the present day is fascinated by the margins, the peripheral and the exotic. Just look at the recent enthusiasm of many anthropologists for the topical writings of Graeber which contain little ethnographic evidence, but rather a set of opinion pieces espousing anarchist convictions which might be considered a typical first world luxury. Certainly by my African colleagues. For it could very well be argued that the (global) South needs more, and not less bureaucracy, provided it is well functioning (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C30bJBcM_0c#action=share; written version in German: written German version: https://perspective-daily.de/article/363/probiere).

The neglect of bureaucracy and bureaucrats might also be the effect of anthropologists going, somewhat unreflectively, native – hasn’t anthropology been described by cynical observers as the study of anybody who is darker and poorer than you are, and do such people not often find it difficult to handle bureaucracy and bureaucrats? Or is it, as Chihab El Khachab suspects, because of the revulsion of anthropologists at “the ways in which university bureaucracies impact scholarly work and constrain knowledge production”?

I propose that in addition, there is an additional, subcutaneous reason for this aversion: bureaucrats are the unrecognized, ‘evil’ twins of anthropologists. After all, as writers, do we not essentially do the same type of work: enquire, summarize, translate, categorize, draft? Do we not, as writers, obey to very similar aesthetic rules as those which Mirco Göpfert (2013) has beautifully described for the case of African policemen? Do we not also try to formulate authoritative statements on the world and attempt to impose them on others? This aversion to the ones who are most similar to us would not surprise a psychologist, and do we, as fieldworkers, not also find those people most despicable who are the closest to us, e.g. tourists?

What indeed seems to be new in the study of bureaucracy, and a perspective which has been mainly developed in anthropology, is the interest in the materiality of bureaucracy, e.g. the paperwork, from Cabot (2012) to Hull (2012), to name only a few authors. This newly emerging focus is, in fact, the result of interdisciplinary cross-fertilization, in this case with science and technology studies. In addition, I would pick up on an idea first sketched by Marcus and Holmes (2006) but, as far as I can see, not much taken up empirically (but see Islam 2015), and argue for another perspective for further ethnographic enquiries, under development with my colleague Jan Beek at Frankfurt: Increasingly, bureaucrats become para-ethnographers. In fact, they even might have been trained as anthropologists, as many people active in the management of migration nowadays are. But in any case, as scientist-practitioners they have to professionally deal with cultural diversity and do their own theorizing, e.g. produce cultural analysis of what they see and experience, much of it in written form, and some of it directly influenced by academic anthropology. In this perspective, the anthropology of bureaucracy has the potential to become a type of increasingly necessary second-degree observation, an ethnography of ethnographers, and contribute to the self-reflection of the discipline in this 21st century (Bierschenk, Krings and Lentz 2013).

References

Becker, Howard, Blanche Geer, E Hughes, and Anselm Strauss. 1961. Boys in White. Students Culture in Medical Schools. Chicago, Ill.: Chicago University Press.

Bierschenk, Thomas, Matthias Krings, and Carola Lentz. 2013. “Was ist ethno an der deutschsprachigen Ethnologie der Gegenwart?” In Ethnologie im 21. Jahrhundert, edited by Thomas Bierschenk, Matthias Krings and Carola Lentz, 7-34. Berlin: Reimer.

Bittner, Egon. 1967. “The police on skid-row: a study of peace keeping.” American Sociological Review no. 32 (5):699-715.

Cabot, Heath. 2012. “The governance of things: Documenting limbo in the Greek asylum procedure.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology no. 35 (1):11-29.

Crozier, Michel. 1963. Le phénomène bureaucratique. Essai sur les tendances bureaucratiques des systèmes d’organisation modernes et sur leur rélations en France avec le système social et culturel. Paris: Seuil.

Freidson, Eliot. 1970. Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge. Chicago, Ill.: Chicago University Press.

Göpfert, Mirco. 2013. “Bureaucratic aesthetics: Report writing in the Nigérien gendarmerie.” American Ethnologist no. 40 (2):324-334. doi: 10.1111/amet.12024.

Handelman, Don, and Elliot Leyton. 1978. Bureaucracy and World View. Studies in the logic of official interpretation: Memorial University of New Foundland, Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Heyman, Josiah McC. 1995. “Putting power in the anthropology of bureaucracy: The immigration and naturalization service at the Mexiko-United States border.” Current Anthropology no. 36 (2):261-287.

Hilbert, Richard A. 1987. “Bureaucracy as belief, rationalization as repair: Max Weber in a post-functionalist age.” Sociological Theory no. 5 (1):70-86.

Holmes, D. R., Marcus, G. E. (2006). Fast-capitalism: Para-ethnography and the rise of the symbolic analyst. In Fisher, M., Downey, G. (Eds.), Frontiers of capital: Ethnographic perspectives on the new economy (pp. 34–57). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hull, Matthew. 2012. Government of Paper- The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Islam, Gazi. 2015. “Practioners as theorists. Para-ethnography and the collaborative study of contemporary organizations.” Organizational Research Methods no. 18 (2):231-251.

Lipsky, Michael. 1980. Street-Level Bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Meyer, John W., and Brian Rowan. 1991. “Institutionalized Organization. Formal structure as myth and ceremony.” In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by P. J. DiMaggio and Walter W. Powell, 41-62. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Monjardet, Dominique. 1994. “La culture professionnelle des policiers.” Revue Française de Sociologie no. 35 (3):393-411.

Monjardet, Dominique. 1996. Ce que fait la police. Sociologie de la force publique. Paris: La Découverte.

Osborne, Thomas. 1994. “Bureaucracy as a vocation. Governmentality and administration in nineteenth century Britain.” Journal of Historical Sociology no. 7 (3):289-313.

Pressman, Jeffrey L., and Aaron Wildavsky. 1973, 3rd ed. 1984. Implementation. How Great Expectations in Washington are Dashed in Oakland; Or Why it is Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation of Ruined Hopes. The Oakland Project. Berkeley, Ca.: University of California Press.

Quarles van Ufford, Philip. 1988. “The hidden crisis in development: Development bureaucracies between intentions and outcomes.” In The Hidden Crisis in Development: Development Bureaucracies, edited by Philip Quarles van Ufford, Dirk Kruijt and Theodore Downing, 9-38. Amsterdam: Free University Press.

Weick, Karl E. 1976. “Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems.” Administrative Science Quarterly no. 21:1-19.